Synthetic Neuron Creation

A conversation with multimedia artist Mike Tyka

Mike Tyka is an artist and researcher with experience in the fields of biochemistry and biotechnology. After earning his doctorate in biophysics in 2007, he continued his work at the University of Washington studying the structure and dynamics of protein molecules. In 2012 he joined Google to work on creating neuron maps of fly and mice brains.

Tyka turned to art in 2009 when he and other artists created a 35-foot-high interactive Rubik's Cube sculpture titled Groovik's Cube, which was exhibited in Reno, Seattle and New York. Since then his artistic work has focused on both traditional sculpture and modern technologies such as 3D printing and artificial neural networks. His sculptures of protein molecules are made of cast glass and bronze, and are based on the structural coordinates of specific biomolecules.

In 2015 Tyka created his first large-format computer graphics works using the iterative DeepDream computer vision program. His latest series of generative works, Portraits of Imaginary People, was exhibited at the ARS Electronica Festival in Linz, at Christie's auction house in New York, and at the Karuizawa Museum in Japan. Tyka’s kinetic sculpture Us and Them was exhibited in 2018 at the Mediacity Biennale at the Seoul Museum of Art, and in 2019 at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo.

Mike Tyka. Us and Them. Kinetic Installation. 2018

You’ve been working with artificial neural networks in an art context since 2015. Can you very briefly introduce our readers to these AI (artificial intelligence) tools?

What is typically referred to as AI in the research community is machine learning. It’s a term that is a lot more specific and precise than AI, which is a broader term with a lot more meanings attached.

Machine learning is essentially a statistical computer science method for programming a computer, based on examples. In a traditional computer program, you write down precise rules by which the computer program should do something (essentially – if this, then that). Machine learning is different in the sense that you don’t write this program specifically. Instead, you feed the computer a significant number of examples and the desired outcome. The computer itself, essentially through mathematical frameworks, extracts the rules that encompass those examples and everything in between. A typical example is facial-recognition – you feed thousands of images of faces into the computer, and pictures without faces as counterexamples. Over time, the algorithm will learn the rules that characterise a picture with a face. These rules are very difficult to nail down to precise commands if you wanted to program something similar manually. This is why the old AI style struggled with these tasks, because these rules are not very clear – they are very fuzzy.

Mike Tyka. A fleeting memory. From the 'Portraits of Imaginary People' series. Archival print. 2017

In your TED Talk (Germany 2015), you compared AI tools with photography. The invention of photography liberated painting from accurately representing reality, and we saw the rise of the Modernist art movements. In the same way, AI tools could liberate contemporary artists. Can you explain this idea in more detail?

The first thing I would say is that it’s not a matter of replacing the old. People still paint realistic images. It just opens up new additional things you can do that we previously ignored or that weren’t possible – like the hyperrealistic painting that combines photography with painting. Also, the abstract forms of art were discovered and became more interesting because the mind opened up to what other things painting can do.

I think that there are some analogies here. For example, there are generative forms of machine learning that, rather than detecting something or categorising something, do the opposite and generate new examples that fit the things they have seen before. For example, you can imagine a paintbrush that, rather than making a line, can draw kind of semantically. You can have a brush that paints dogs or something else. Later, you can compose larger images from these generated elements, but the artist’s attention shifts to a different level, just like with photography. As an art tool, photography meant that you, as the artist, were not concerned about reproducing an exact image but were now thinking about something more abstract or global, and this frees up your mind to do other things. AI tools can also be this way.

There is another aspect that is perhaps closer to the work I’ve been doing so far. Training the AI is interesting because you can feed it images and have this dynamical system to play with to see the result. I sometimes compare it to splashing paint against the wall or similar art techniques where you also relinquish a certain level of control over the details and have to respond to what is happening. When you are splashing paint on canvas, you don’t exactly know how it’s going to land. You have some, but not very much, control. There is a moving back and forth with a system you don’t fully control. Similarly, when you work with a machine learning algorithm, it is a little bit like that. You build your system yourself and determine what goes in it, but a great number of dynamics are happening in the system that you don’t fully control, and instead, you just respond to it. It becomes almost like a collaboration with the system.

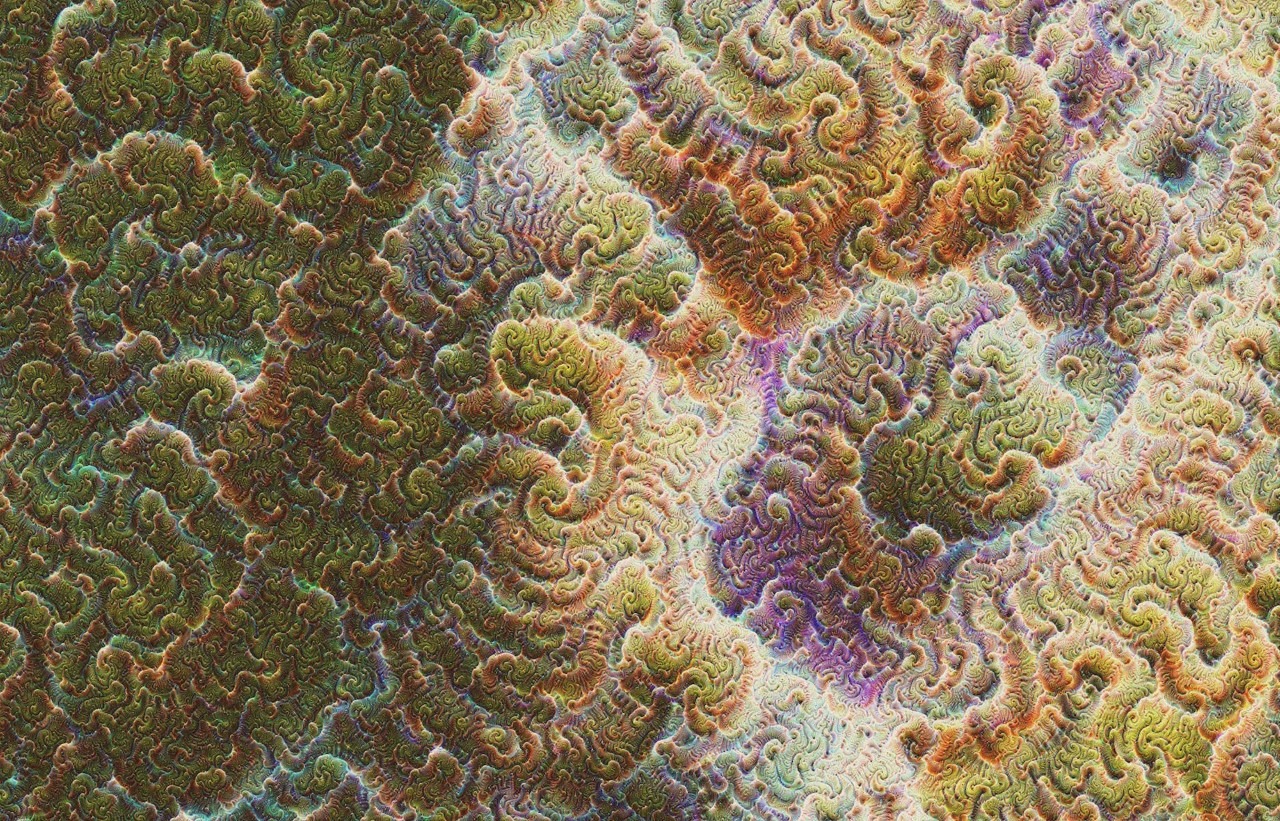

Mike Tyka. Castles In The Sky With Diamonds. Neural net, Archival print. 2016

Mike Tyka. Carboniferous Fantasy. Neural net, Archival print. 2016

Do you have any predictions about new AI tools that will soon be used by artists?

Predictions are always hard, but if we can use the last three years as an example, the computer science field of machine learning is moving very quickly – new techniques are coming out all the time and getting more accessible. When GANs (generative adversarial networks) first came out, people started using them for art purposes shortly after. We can look at the cutting edge of machine learning now and be relatively certain that someone will start using these newer techniques for art.

What’s on the cutting edge? Reinforcement learning. It is a style of learning where the algorithm keeps choosing actions and examples to learn from itself. When you are training a GAN, you choose the examples, but in a reinforced learning context, you have an algorithm that goes out itself and takes actions based on what it has already learned, for example, choosing a specific image. There is an action and reward system in the algorithm that guides this process. You can build algorithms that evolve themselves, but I haven’t seen this learning style used as much in art, yet, at least for now.

Why are these reinforced learning algorithms not very common in the context of art? Do they require too much computer power?

That’s a good question. I think that they are harder to build and harder to get working. They are more technical.

Artists have to deal with a lot of technical stuff to learn and use the algorithms that are coming out. Some people try to make this process easier. Runway [a general-purpose platform for AI – Ed.] is a good example of making these algorithms more accessible to people with less technical backgrounds. If you take an algorithm and make a user interface around it, that makes it easier to use, but you also limit your ability to create something very unique and novel. It limits the options of what you can do.

When many artists use the same tools, these limitations can result in similar artworks –you can already see this phenomenon if you follow multiple AI artists or AI-art-related online groups on social media. Is there a way to avoid this problem of merging with all the other AI-generated artworks? How can you create something original when you have these limitations?

Part of this is because of the things we already talked about. Because it is hard to get into the guts of these tools, a lot of the aesthetic that is coming out of any given algorithm is quite strong. GANs are a good example. They all resemble each other very strongly. The same is true for Deep Dream or Neural Style Transfer. These aesthetics are a consequence of the algorithm’s fundamental happenings, and if those are not being changed, the aesthetics are also not changing. It can change because of the data you put in, but there is an intrinsic look and feel that comes from the algorithm. If changing the algorithm is hard because it requires technical knowledge, then it is hard to deviate from this aesthetic. It takes a lot of work and a deeper understanding, but as more people are coming to the field now, there is a lot of cool and exciting stuff. Even just using the tools as they are, but in a new way that has not been done before, can result in something interesting.

Different people have different goals. Some of us live at the edge and try to find untrodden ground to explore. Other people are more about taking an area that has been done before and doing it better. There are the ‘first word’ artists and the ‘last word’ artists (Michael Naimark introduced this distinction). ‘First word’ artists are the ones who try something new and break ground in a new area, but it often is not the best example of the new genre or sub-genre. Later, someone will have the final word on that and really nail the technique.

Mike Tyka. Here Was The Final Blind Hour. Neural net, Archival prin. 2016

Lately you’ve been using neural networks in the context of moving images, and you have a new project called EONS. Can you tell us more about this work? Are there differences between using machine learning for static images and moving images?

EONS was an attempt to create a story arc with the AI tools I was already working with. They are trained on static images (the algorithm was not trained on movies), and the algorithm is used to assemble a changing picture. I was interested in creating an animation that tells something in the temporal space.

Over the last three years I’ve been interested in climate change, and that influenced the topic of this art piece. In the short time that we exist on this planet – as compared to the earth’s geological time scale – we quickly forget how small we are. We can change the earth dramatically, but in the very long term, we are insignificant. This idea lent itself well to this slowly moving and morphing imagery.

Mike Tyka. EONS. 2019

This AI approach requires a lot of data. You need thousands of photos to train a network properly, and this could be a challenge. You used images from Flickr for your AI project Portraits of Imaginary People. Are there other methods that can be used when an artist needs such a large amount of pictures or other kinds of files? Do any problems arise when working with such large data sets?

Indeed, it is difficult, and a lot of the work in training a neural network is just cleaning and organising the data. I don’t precisely know where other artists get their data, but there are multiple ways. Creating your own data set (going out and taking images) is a lot of work, but it also makes something super unique. You can really take control of the output. If you use something public, that is not the case. Also, not all algorithms require large data. GANs do, but something like Deep Dream or Style Transfer don’t.

Can you tell us about your work Portraits of Imaginary People and the process behind it?

I did the work in 2017, and at that time people were starting on training GANs on faces in the machine learning world. I thought it was very interesting to think about imaginary people in the context of manipulating opinions, which was really happening on the internet with fake accounts. This was happening during the 2016 USA elections. It's a new way of doing propaganda. Old-style propaganda came from state actors and was top-down, but the internet created an entirely new way for somebody to infiltrate the population and create fake identities that people relate to. We are group thinkers as humans, and susceptible to this kind of thing. So this imaginary person plays a pivotal role in this mechanism.

Mike Tyka. maksimkovalev15. From the 'Portraits of Imaginary People' series. Archival print. 2017

In reality, those were probably a few dozen of people who were managing this large number of fake accounts. With the ability to generate fake avatars and the text that they write, you can see that this kind of operation could now be scaled up and automated. A small number of people could create thousands of opinions that are being sent out into the world.

Since that project, this technology has become photorealistic, and there have been examples now of people having used progressive GANs in this context. That led me to the project called Us and Them, involving printers. I combined these avatars with text. In this case, the text was created by an algorithm trained on actual tweets that people were using in the 2016 campaign. What comes out is what came in – tweets shouting racist things and trying to polarise the public. But you can theoretically use it on anything. Give a small number of examples, and amplify that.

Mike Tyka. Us and Them. Kinetic Installation. 2018

Mike Tyka. Us and Them. Kinetic Installation. 2018

Fake news is not the only social and ethical issue raised by the advances in AI technology. We can also create AI systems that have all kinds of biases because there was a bias in the data or data gathering methods. Do you think that artists have some kind of responsibility when they use these tools? Should they reflect on this dark side of AI when they make their art?

To me, this is one of the more interesting aspects of AI art – to be self-critical in this way, but artists can do whatever they like. It is totally legit to make art that just looks pretty. I don’t think that there is an obligation to be critical. An exception could be if someone makes art that glorifies AI without acknowledging the bad effects (this is also true for all kinds of technology) and the fact that you are creating a biased opinion. In this case, it would be better to have a more balanced approach, but I haven’t necessarily seen that many bad examples.

What are your thoughts about AI depiction in popular culture, such as in movies and video games? There is also a lot of glorification, or, the exact opposite – AI portrayed as an evil, anthropomorphised robot.

Yes, Hollywood doesn't do a good job and goes in these two extremes. Suppose people are afraid of AI taking over the world like in this terminator narrative, in which machines pick up a machine gun or start a nuclear war. In that case, it is not useful because the true negative effects of AI are less noticeable, e.g. job displacement from automation, or bias in decision making by algorithms. When people keep worrying about AI one day taking over the world, it distracts them from the problems that are happening right now and that deserve that attention. So this sensationalism is not helpful, but of course, this is what Hollywood is good at – making drama. It is much harder to create a dramatic movie about worker displacement.

It also seems that these technologies blur our understanding of copyrights. You probably know of the example of the researcher who trained a neural network on the movie Blade Runner, and the AI system later visually reconstructed the movie. The reconstructed video was eventually taken down from Vimeo because of copyright infringement claims. Should we change our understanding of copyright?

This is a very interesting and difficult question. For example, if I take a bunch of copyrighted artworks and train a neural network from them, does the copyright transfer to the parameters of that network? Does it transfer to the outputs of the network when it generates new images that are similar to the input? But if the variety of things the network was trained on was copyrighted in its own right, the result is some kind of strange remix of these things that are arguably novel. If the output is different from any given input example, is that copyrighted?

As a counter-example, all the music that I listen to is copyrighted by those artists. If I were to compose a song, obviously, I would be influenced by everything I have heard. Nobody comes out of a vacuum. The rules in the music industry state that if the output you produce is sufficiently different from any previous example, it is novel. I don’t precisely know the rules they use, but they must have some kind of criteria.

Nobody has a problem with the fact that you are learning from copyrighted materials. That is our intuitive understanding of copyright; otherwise, nothing could ever be made. What matters is that the output produced by your brain or an artificial brain (AI system) has to be novel, but I don’t think it should matter what you feed into the algorithm.

Mike Tyka. Cellism. Neural net, Archival print. 2016

You are a fascinating person because you are a scientist and an artist at the same time. You have a PhD in biophysics and work with computer models to understand the smallest blocks of biology. Simultaneously, you are making sculptures, installations and AI-generated artworks and participating in art exhibitions. In the TED talk that I mentioned earlier, you said: ‘I work in the daytime with technology, and at night time I make art.’ How did you end up with this dual lifestyle?

I don’t know. I go back and forth. This year I spent almost no time doing art. Since the beginning of Covid-19, I’ve worked almost exclusively on science and really enjoyed that. I realised how important it is to my soul, but I will later flip back to the art side, sooner or later.

Ever since I was a kid, I have been doing both things. When I was small, I played with computer animation. I would make these little animations with code, and my dad would say ‘this is cool, but what is it good for?’ What I didn’t realise at that time is that it was simply art. It wasn’t good for something in a utilitarian way. It was just exploring an interesting system.

Then I focused more on my science side and studied biochemistry and biotechnology; but later, the art came back and knocked on my door. Of course, what was in my head at that time were these beautiful protein folds. These are very interesting structures, and I started making art of them and ended up with molecule sculptures.

Mike Tyka. Tears. Lysozyme with carbohydrate. Cast bronze, Cast Glass, Wood. 2015

Mike Tyka. RThe Annealing - DNA. Cast glass, Cast bronze, Vera wood. 2016

In Western culture, we tend to separate science from art. We see them as very distinct practices. Maybe this separation is too strict and, in a sense, even harmful to both science and art. Your approach, in some way, is blurring this line.

It’s unfortunate, and it hasn’t always been this way. Only a few hundred years ago, you had a lot more mingling of them both. The same people (I think of the Renaissance painters) were both interested in anatomy itself, from a scientific perspective, and they were also artists. They used this knowledge to make more anatomically correct paintings of humans, and that was revolutionary.

It works the other way, too. The communication aspect of science relies heavily on art. Perhaps it is not a surprise that we have people who think that the Moon landing didn’t happen and that vaccinations are harmful. There somehow is a breakdown occurring between the ivory tower of science and actually making science understandable to people. Science doesn’t do that, and so it loses its support. We have to share the understanding of science in a way that is accessible, and art is an important way to do that. It can make things visible. A lot of the things we examine in modern science are not visible. Proteins are smaller than the wavelength of light. You can't see them. To make them visible, you have to choose a representation, which is inherently an act of art.

Do you think that we will see more of this artist and scientist hybrid in the future?

The scientific boundary of what is known has moved so far that you sometimes have to spend a lifetime learning to understand just the research problem you are trying to solve. Only at the end of my PhD did I start to understand what the issue was. It’s also hard to study art and all of its complexities. It’s a lot for one person.

In the 18th century there could exist such a thing as a well-educated person with extensive knowledge in multiple fields, but now this seems almost impossible.

Yes; even in one science area you have to specialise, which inherently makes you more isolated. Even bridging two or three fields is hard. In the 18th century it was easier to be a physicist, biologist and an artist all at the same time. I think this is a challenge for humanity because it will only worsen. After all, we are always adding more to our collective body of knowledge.

Do you have any upcoming projects?

As I mentioned, in the last year I’ve been focusing more on science work again, but I have been working on an exciting new protein sculpture done in both glass and metal, and I'm excited to unveil that in the coming months.

Mike Tyka