We don’t know how, but it works

An interview with artist Tamiko Thiel

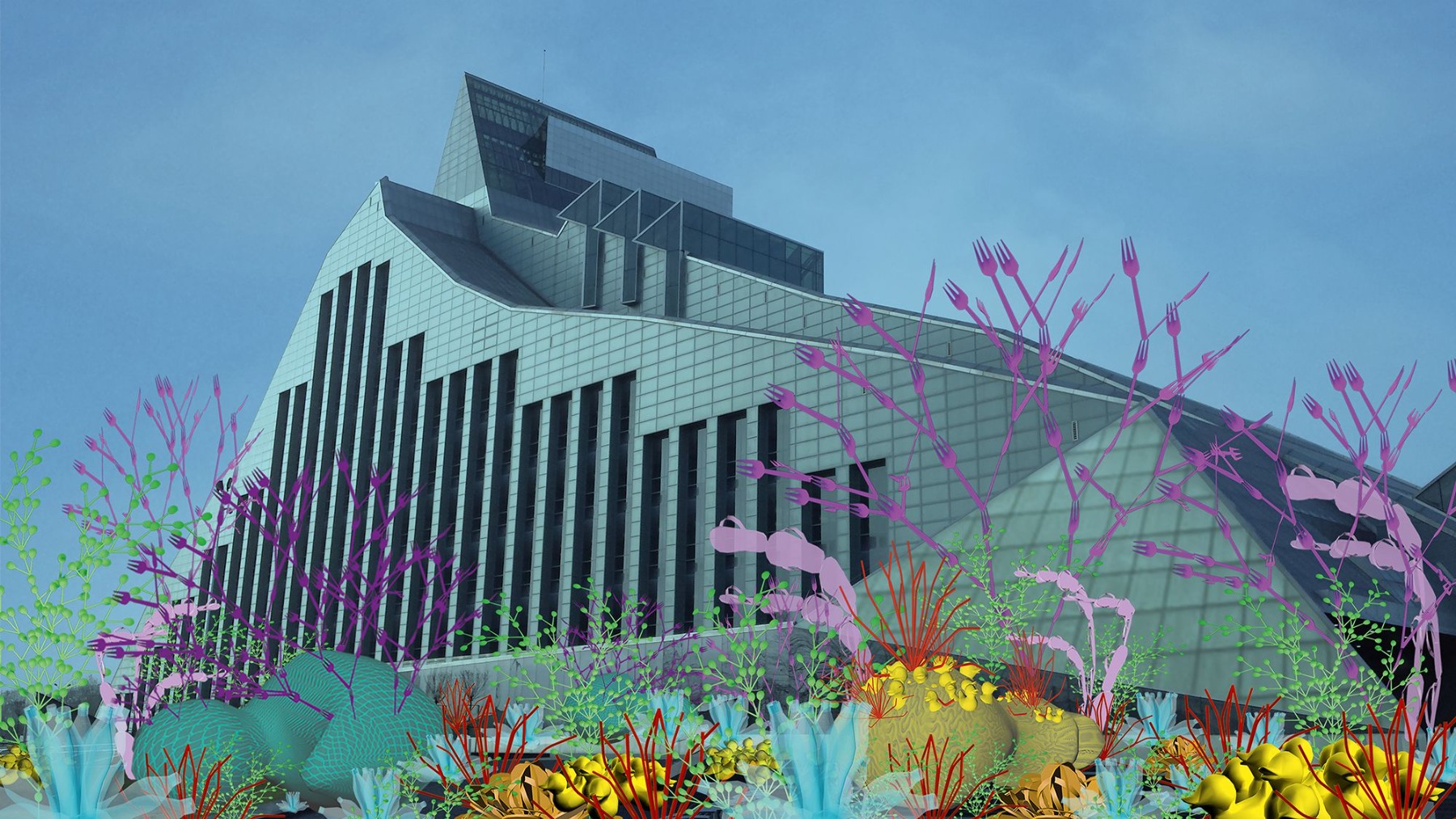

On 9 October of last year, the exhibition “ECODATA” opened at the National Library of Latvia as part of the annual RIXC Art-Science festival organised by the RIXC Center for New Media Culture. Unfortunately, the show had to close early due to the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic that overran Latvia in late October. However, one of the works is still there and probably will be for some time, visible both in the atrium within the Library and also outside the building. It is an augmented reality piece, “Unexpected Growth”, by American artists Tamiko Thiel and her partner /p. The work is visible with the help of a mobile application and displays images of plastic trash formed into corral reef-like formations.

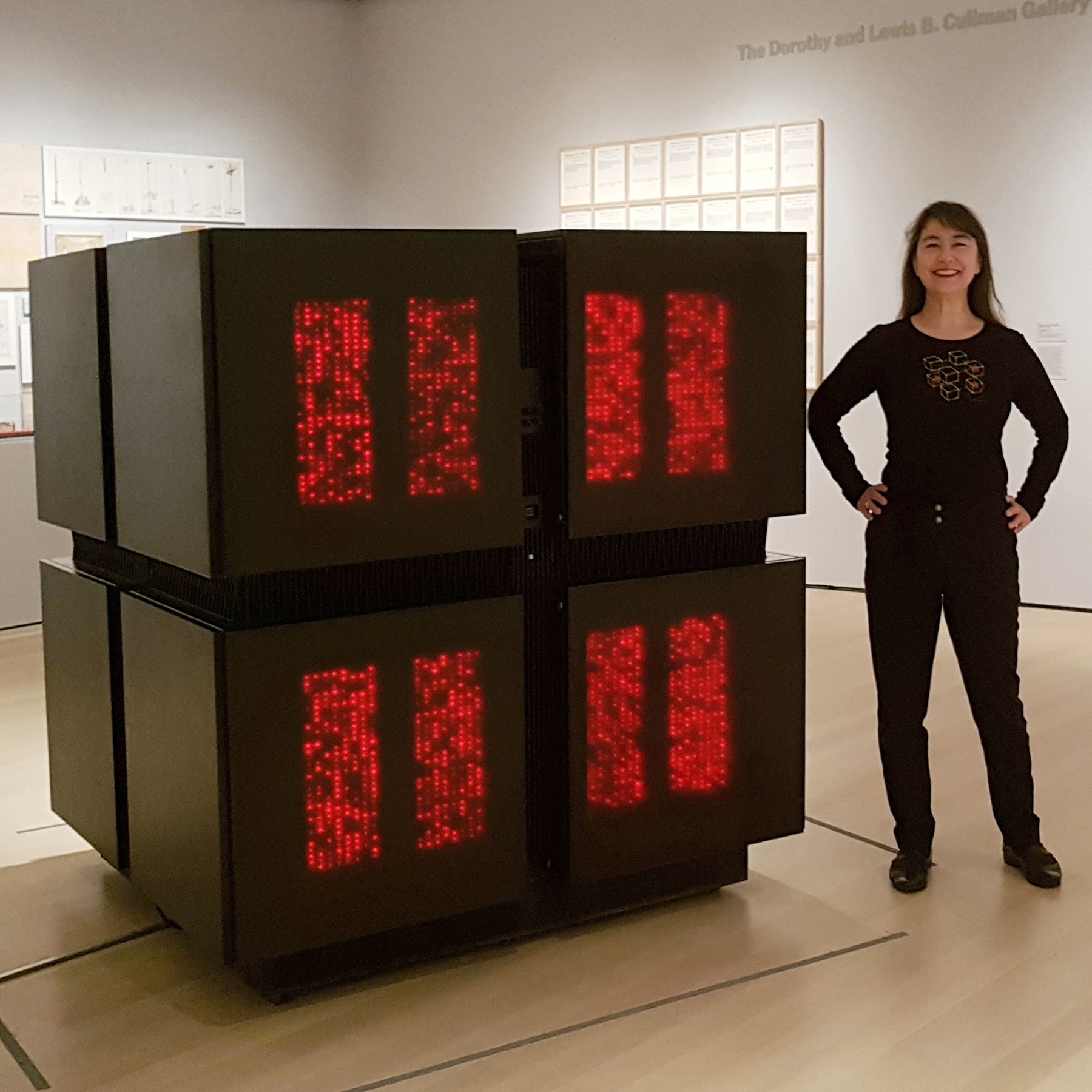

Born in 1957, Thiel studied product design at Stanford University and mechanical engineering at MIT. During the 80s she entered the field of human-machine design. While working for Thinking Machines Corporation with entrepreneur and scientist Danny Hillis, she was lead product designer for Connection Machine CM1/CM2, which was the first commercial AI supercomputer and, in 1989, the fastest computer on Earth. CM2 is now a part of the collection of MoMA. In 1991 Thiel received a Diploma in Applied Graphics, specialising in video installation art, from the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich.

Since 2010 Thiel has been making many augmented reality works, and since 2018, also in collaboration with the German artist /p (pronounced “slash p”), such as “Unexpected Growth.” In 2018 she was awarded the Visionary Pioneer Award by the Society for Art and Technology Montreal for “over 30 years of media artworks exploring the interplay of place, space, the body and cultural identity in political and socially critical artworks”.

Could you tell me about the motivational history behind “Unexpected Growth”?

Christiane Paul, who I’ve known since 2002, is the curator of media art at the Whitney Museum. She had shown my work at various exhibitions around the world, but 2018 was the first time she was able to do a huge, entire-floor-of-the-museum show at the Whitney consisting of pieces from the collection of digital works that they had collected over decades, most of which had never been shown at all. New media art has finally achieved a status in the U.S. where it’s starting to be considered a legitimate art form, which was not true five years ago. So, in spring 2018 I got an email from Christiane asking me if I could make an augmented reality piece that has some sort of algorithmic component for the terrace of the museum. There are these Lindenmayer systems, L-systems for short, that both /p and I had long been familiar with from computer graphics. You know, in a lot of cases when in virtual reality you see plants or trees or bushes or whatever, they are generated with this algorithm that has just very basic rules for growth – for instance, there is a stem and a leaf, and then there is another stem and a leaf with a little rotation, and again another stem with a little bit of rotation, and so on. Just really, really simple rules like that. So, I and my partner /p decided to create an AI work that used L-systems for generating the basic components. Then the question was – what sort of components? The standard is that you have something that looks like a stem or looks like a leaf – a particular type of plant that you’re trying to mimic. But I didn’t want to necessarily mimic natural systems; I wanted to be a little bit more creative than that.

The Whitney is right on the Hudson River, and I had been working for a number of years with issues of climate change, looking at what sort of plants, both land and marine plants, would be able to survive climate change, or which ones were especially endangered by climate change, how do rising water levels change our map of the world, what does the world look like when you have water levels at various heights, etc. So it was a natural thing to think, “Well, let’s put the Whitney under water!” But that’s sort of a science fiction prediction of the future – you know, what sort of future are we steering towards with the actions that we are doing right now. That is what I like to speak to in a lot of my artworks. So we decided OK, let’s put the 6th-floor terrace of the Whitney under water. And I had also been looking into the problem of plastic pollution – of course, there are very shocking images on the Internet of dead albatrosses with stomachs full of plastic and stuff like that… Those images have been around for years! When my husband and I would vacation in Greece, Indonesia or Malaysia over the past number of years, at some point we started to realise that the sort of pristine beaches that are everyone’s dream of a tropical vacation is an artefact of beach-side resorts. They send out their staff in the early morning hours, before everyone wakes up, to collect all of plastic that’s accumulated. This became especially clear to us in 2013, I think, when we were in Malaysia. There was a beautiful beach, as usual, but we went for a walk a little bit outside of the compound, where it wasn’t a resort anymore – it was just an area of public access to the water. There were villagers who were fishing, who literally live in houses on stilts in the water, and the beach was covered in plastic because no one collected it every morning. We realised that that is the standard state. And then, at the beginning of 2018, the same year as my commission for the Whitney, China declared that they are no longer going to take garbage from other developed countries such as Japan, the USA or Europe.

What do you mean by “take”? In what way did they “take” it?

Well, we sold it to them. Western countries pride themselves on their recycling programmes and how clean they are. But there are many, many different types of plastic, and only three of them actually have any value as recycling material. The rest of it is burned in incinerators or thrown into dumps, which at some point turn into small mountains. Or – and this is what most countries were doing – you put it into a container and ship it to China, and China disposes of it in whatever way they see fit. But China was becoming large enough, powerful enough and rich enough that they didn’t have to make money that way anymore. In January 2018 China said – we will not take your waste anymore. And all of a sudden it became public knowledge that all of these wonderfully ecological, green states and countries were actually just sending their garbage to other countries to be disposed of in open-air burning sites or simply dumped into the countryside or into the ocean.

So, all of a sudden, all the European countries, the USA and Japan are wondering – how are we going to deal with all this garbage? Suddenly it’s public knowledge that it’s not just China, Malaysia and Indonesia that are so polluting – the whole world is causing the problem. It’s just that until now it had been “out of sight, out of mind”. So I wanted to bring that sense of being surrounded by plastic garbage back to the West, if you will. We’ve got these Lindenmayer growth systems, which if given the right natural-looking components, give you beautiful trees and bushes and other plants, but I decided – let’s do it with virtual plastic garbage, such as the yellow rubber duckies.

I think it was 1992 when a whole container full of bath toys went overboard near Asia. Not only yellow rubber duckies, but also green frogs or whatever. But the rubber duckies are somehow iconic. A container in a storm went overboard, and then scientists started realising that they could use these rubber duckies to track the flow of currents around the world. At first they started finding them on the western coast of Canada and the US, and now they have found them all the way to Greenland and Scotland. Some of them, apparently, actually went up to the Arctic. At that point the Arctic was still freezing over. Now it’s not. But back in the early 90s it was still freezing over, and so the fact that the duckies came up into the Arctic from Asia, and then travelled across the whole breadth of Canada, and ended up in the Atlantic, taught scientists a lot about oceanic currents that even go through areas we thought were frozen and static.

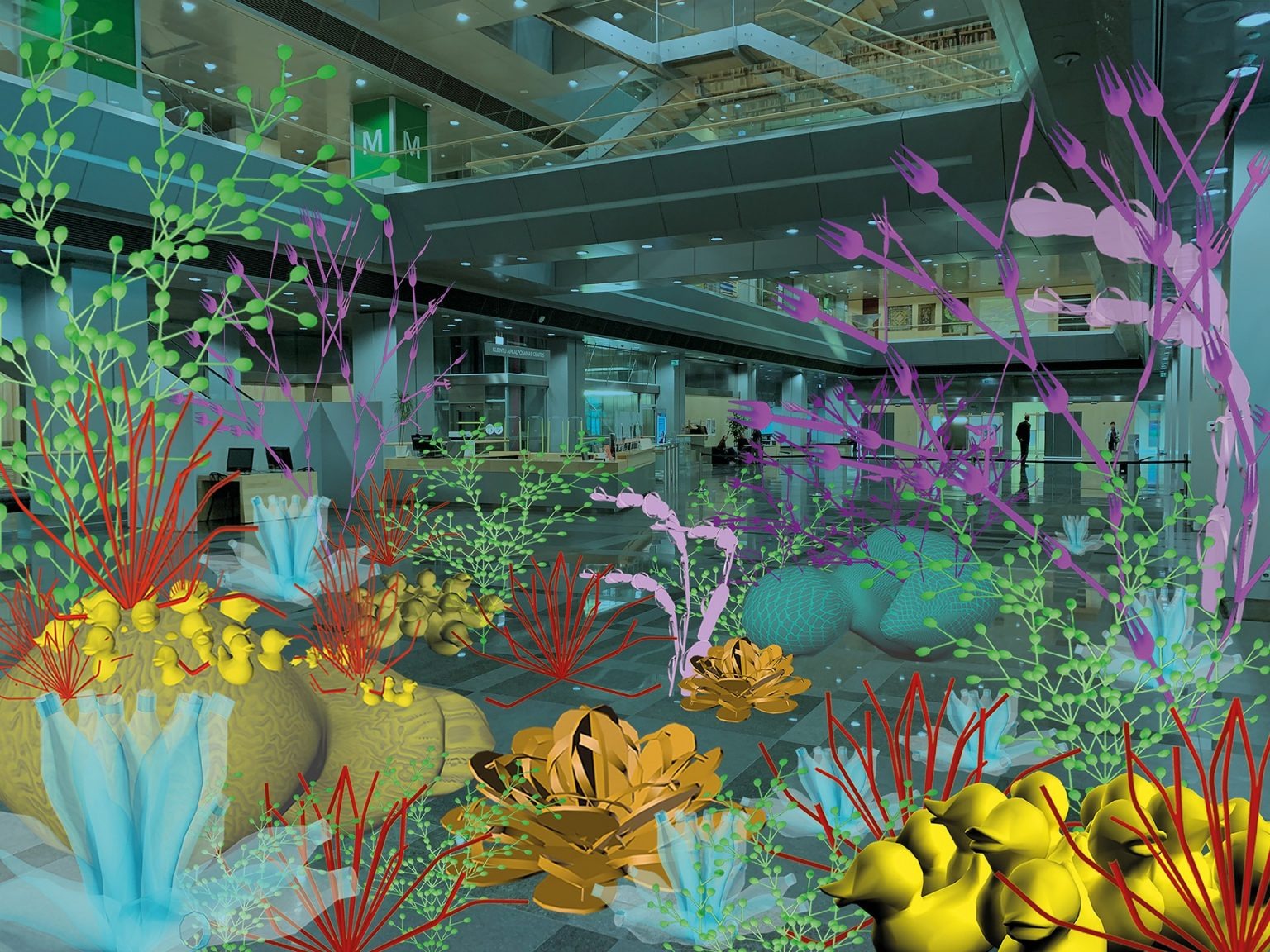

Unexpected Growth, augmented reality installation, Tamiko Thiel and /p, 2018. Visualization in the National Library of Latvia. Originally commissioned by Whitney Museum of American Art, and in their collection

Anyway, the yellow rubber duckies became iconic at that point. A sort of harmless thing – oh, isn’t it cute, with the rubber duckies you can see how the currents flow around the globe. And then, in the years since then, we started realising – wait a minute, that’s not the only plastic garbage that is flowing around the world. Then the Pacific trash vortex was found. So the yellow rubber ducky is iconic as the first indicator that plastic, in the sense of synthetic products, was really travelling all over the world. So, in “Unexpected Growth” there are pieces that are various constructions of yellow rubber duckies, and then there are larger rubber duckies – which I call “ducky reefs” – lying on their sides, textured in some way and with other things stuck in them: plastic forks, plastic spoons, the red ones are plastic straws…

And then, of course, the other iconic item of plastic garbage – water bottles. In the West, bottled water is usually expensive mineral water, but in a country where you can’t drink the tap water, bottled water is really the only way of not getting sick every time you need to take a drink. So, if we ban plastics, there’s going to be a huge problem – how are people going to get water that’s safe to drink?

Once we say that we have to change how we’re doing things, all sorts of new problems appear. It’s a calculated idea that is found in all my artworks – to not hit you over the head with it, but to present something that’s maybe beautiful and hopefully fun to engage with, and then once you’re engaged with it, if you spend the time looking at it, you start realising – wait a minute, there’s something wrong here! That’s what I’m trying to do with “Unexpected Growth”, to get people to say – Oh, look at this beautiful, colourful reef! But then they go – Wait a minute, oh my god! It’s an art experience in which you, by your own free will and volition, surround yourself with plastic garbage. This is a sort of exhibition that I can do over and over again, in different places around the world, as well as post the images on social media so that it stays in the public consciousness in a very different way. Obviously, images of dead albatrosses with plastic-filled stomachs are more gripping both emotionally and intellectually – they really show you the problem in a very, very direct manner. But I have a hard time looking at those. I won’t look at those images over and over again because it’s just too depressing.

Why “unexpected”? Because we were unaware of it for such a long time?

Yes; it’s not what you look for when you look at natural systems – you don’t expect a growing object to be composed of plastic. In nature there are hermit crabs that will take on a plastic object instead of a shell when they’re looking for something to hide in as their home. So, there are certainly direct examples of animals and plants who are now incorporating plastics into their structures. Of course, a more heinous example are the microplastics that are inside – they are causing damage inside organisms, and we don’t see it. A lot of my work is about taking processes or problems that are essentially invisible to the naked eye, or that are not in your daily environment, and, through the medium of augmented reality, put you into a virtual environment that you would not be in otherwise. And it then gives you an emotional relationship to this topic that you would not necessarily have otherwise.

You yourself never physically came to Riga. How does this work – installing an artwork like this in a specific site, a specific place, if you have not been there yourself?

It takes a lot of work. This piece, and a lot of pieces that I do that are very large installations, are geolocation-based augmented realities. Each of these objects is given a GPS coordinate.

Unexpected Growth, augmented reality installation, Tamiko Thiel and /p, 2018. Visualization in the National Library of Latvia. Originally commissioned by Whitney Museum of American Art, and in their collection

As in each rubber ducky, each spoon?

Duckies and spoons don’t occur individually but as part of a larger Lindenmayer structure that I am calling an object. Each of these needs a GPS coordinate in the museum. I’d have to look, but there are around a hundred objects that we have to space out in the museum. One thing I can’t tell without going there, or without asking someone to make a recording while walking around, is if your GPS updates or not while you’re walking around. If you’re outside, for instance, you can walk around the plaza outside the library, and you will also be surrounded with “Unexpected Growth”. As you walk, your GPS position is changing, and one of the properties of our app is that it will sort of move around you so that as you’re walking, the ones that you are leaving behind will disappear in the back and reappear in front of you. There is this constant shifting and moving, which also gives the feeling of being within a living reef rather than just a sort of dead object.

In an email you sent to my colleagues some time ago, you stressed the difference between the concepts ALife and AI. Could you elaborate on that a bit?

Yes, ALife, or Artificial Life, is a subset of AI. My first contact with AI was in the 80s, when I was a graduate student at MIT. I wasn’t taking AI classes, but I was in the social circles of the MIT AI lab, and then I became the lead designer of the Connection Machine because one of my friends at the AI lab, Danny Hillis, created the company Thinking Machines to build the Connection Machine supercomputer, which he was inventing for his PhD thesis. He asked me to join the company three days after I graduated with my master’s in mechanical engineering. The earliest phases of AI were in the 60s, so this was the 2nd wave during the 80s, when it actually became possible to build supercomputers that were designed specially, for instance, to implement neural networks. The Thinking Machines scientists were working on the very first navigation programs, which led to apps like Google Maps, and the very first natural language input for search engines. All that research was done using the Connection Machine. And in the 90s, scientists like Rodney Brooks at the MIT AI Lab started using ideas that came out of 80s AI to say – maybe chess is not the best example of intelligence. Maybe if we look at insects or very simple life forms that seem to exhibit complex behaviour, we can model that behaviour by using simple rules. For instance, each little unit – let’s call it an artificial ant – each ant is supposed to go out and look around for some food, and when it finds food, it brings it back to the ant nest. And if you have 100 little software ants all going out looking for software food, then it looks like someone is sending them out and giving them instructions, and they are all coordinating with each other. They’re not – they’re just following simple instructions. And that sort of simple instructions that produce complex behaviour or complex objects, like Lindenmayer systems, was all part of the ALife branch of AI that was happening back then. These days people are doing similar things, but somehow the term ALife disappeared when the great AI winter started in the late 90s.

Could you explain what this “AI winter” is?

In the 90s in the U.S., most of the funding for supercomputer research had come entirely from the U.S. military – defense research projects. All of a sudden, after the Soviet Union had dissolved in the early 90s, they had no more excuses to spend massive amounts – millions and millions of dollars – on supercomputer research. So the funding was cut, and the money that companies like Thinking Machines or Cray Computer Corporation needed to support development for AI supercomputers was not available anymore.

Is this winter over?

I think a seminal moment when the AI winter began to end might be 2010. In the early 90s Sergey Brin, who would go on to become a co-founder of Google, learned parallel programming on the Connection Machine as an undergraduate. In 2010 he and Larry Page, the other co-founder of Google, bought Danny Hillis’ second start-up, a semantic networks company called MetaWeb. Danny’s MetaWeb co-founder, John Giannandrea, became head of AI at Google. So that technology, the Connection Machine, flowed directly into Google through this purchase and through Sergey Brin’s knowledge of the whole programming paradigm that Danny had developed for the Connection Machine. Their parallel programming algorithm MapReduce was based on the parallel programming paradigm of alpha mapping and beta reduction that Danny described in his book “The Connection Machine.” Search became better and better, and then Amazon started using AI technology developed by Pattie Maes from the MIT Media lab in order to look at what you had been buying on Amazon and present you with suggestions that might interest you.

All this technology started flowing into systems that we are using as part of our daily life, searching for things, navigating, buying things. It started to become clear that there were useful commercial applications for AI – despite all the nay-saying. And then, you know, at some point people realised that these neural networks can do deep learning to start identifying trends, identifying faces, engaging in deepfake technology or whatever. At the point at which the neural networks were back in the 80s, we were able to build networks with only a couple of levels, and it turned out you needed massive levels for your neural networks, and you needed massive data. Actually, early criticisms – when I say early, I mean, like, in the 80s – of AI was that it could not work; that it was physically impossible for it to work because it needed such huge amounts of data. Then, all of a sudden, with Web 2.0 – which is when people started uploading their own data onto the internet – we had massive amounts of data that could be easily drawn on by supercomputers and by neural networks, and all the pieces came together.

Looking back to the 80s, when you were participating in creating the Connection Machine, can you compare what your thoughts were at that time to what you’re doing today? Like, on a large scale – what do you think when you look back and see how things have progressed?

You know, it hasn’t changed, not at all. What has changed is that now there is the technology to make it happen. In 2015, when I was negotiating with MoMA to see whether they would acquire one of the machines, I went back and did interviews with Danny Hillis and with a number of my other close friends who participated in creating the first machine. We talked about the ideas they had then and what’s happening now, and how they see that, and basically they all said – our dreams are coming true. Many of them actually still have the dream of general AI, you know – the dream that we are creating machines to bring on the next step in human evolution. Humans enhanced by the power of machines will be something greater and, at some point, when machines can learn and evolve on their own, they will supersede us. A lot of them still think that way, they still have that dream.

Do you share this dream?

Well, I believe in the concept of a cyborg, because if you take away my glasses, it’s difficult for me to operate. And as I get older, you take away my tooth implants, and you take away the bodily supports – take away all the medicine I have taken all my life – I probably wouldn’t be alive at this point and I’d certainly be a cripple if I hadn’t used technology to augment my body. At this point – take away your smartphone. How well can you function without your smartphone? We are all cyborgs. We are already there.

And this year, under lockdown, is really the use case scenario that the virtual reality people had been waiting for for decades. Now it makes sense. Let’s meet in the virtual world, whether that’s the virtual video world, like the Zoom conference here, or, if we actually meet in the 3D world, where we can run around as avatars – I mean, that’s all technology that I was doing in the mid-90s, when I started doing VR. Back in the 80s people were saying we need algorithms we trust; we can look at a piece of algorithm, we can look at a piece of code, we can follow it and say – OK, we know how it works. Neural nets are spooky because you can’t see how they work, you can’t take apart the black box and find the homunculus inside the box – you take apart the black box of the neural network, and there’s nothing there. Because that which makes a neural network function is the connections in-between, and that’s exactly why Danny Hillis’ machine was called the Connection Machine – because it had 64 000+ very simple processors, and the computing power was not in each processor but in the connections between them. And this is modelled after the human brain. Take one neuron – is that neuron smart? No. But you put a billion of them together, and somehow – and we still don’t understand how – all those connections create what we consider to be sentient life, human life, human consciousness. Back in the 80s and 90s people said – neural networks can’t work because we don’t understand how they work. Well, we still don’t understand how an individual neural network works, but we know it’s effective. Now it can correctly identify some random photograph as being a photograph of me; it can generate a face that’s so close to being a real human that even though you tell me it’s a fake, I can’t see what betrays it as a fake. So, we still don’t know how they work, but we know that they do work. And we know that a lot of companies are making incredible amounts of money on it, whether it’s by selling deepfake videos and images, or by recognising data or whatever. So, the fact that it works has overruled the fact that we have no clue how it actually works. And that’s the only difference – the difference is that it works.

Do you believe that strong AI is possible?

You mean “strong AI” in the sense of creating an intelligent machine?

Yes, one that has a consciousness of itself.

The difference between intelligence and consciousness, at some level, is like... do you believe in the Turing test? It says that if I can’t tell the difference, then for all practical purposes, as far as I can tell, the other is conscious. I mean, you could be a deepfake! Here, on Zoom – you could be a deepfake. Someone’s created a deepfake that they call Helmuts Caune, and as long as you react to me in a way that convinces me, how can I tell? I don’t know if you’re conscious or not. I can’t tell.

Well, sure, yes.

So, if a machine can do a performance for me that’s as good a performance as you are doing right now, what am I supposed to say? I can’t tell if you’re conscious or not.

But for some reason, it seems to matter to us what the machine itself experiences. Or whether it experiences something at all.

It matters to us conceptually, but I don’t think it matters to us emotionally. The example that I really love for this statement of mine is the Tamagotchi. Do you remember the Tamagotchis?

Oh, yes!

Did you have one?

Maybe I could still find it somewhere in my childhood home. I had a pretty good one.

Ok, so talk to me about your Tamagotchi. What was it that was compelling about it? Why did you even engage with it?

Well, first, everyone in school had one; there was no way around it, really – I had to have one, too. That was a long time ago, but I remember that it elicited a kind of zeal – a drive to raise it and feed it and see it grow. You know, the drive you get when you’re playing a video game or when you’re gambling. But I don’t really remember whether I really engaged with it emotionally, or started perceiving it as a being, you know – as a thing you had to take care of. It was a long time ago.

How old were you?

Eight? Nine? Something like that.

But it also had the same power over adults. You certainly can’t say it was just because you were a kid. There were plenty of examples of adults who also got sucked in by them. And none of us said, “I think this thing is alive, I think this thing has a consciousness, I think this thing is communicating with me.” We all knew it wasn’t. So, even though we knew it was just a gadget – a little machine with no consciousness, no internal life – we still engaged with it at a compelling level. If in your adult life you engage with something at a level such as you could have with your partner, at some point you might say – it doesn’t matter to me, I know it’s an object without a consciousness, but it fulfills my emotional need for a partner.

Like in the movie Her.

For instance. So, does it matter?

Well, one area where it seems to matter, for instance, is AI Art – as in, art that’s created by AI, by computer.

Like the images created by the group Obvious?

Yes, that was actually the example I wanted to mention. We perceive it as art, but it raises questions about the status of an artwork.

If you go to their website and look at what they say about art, the art that they’re making, they talk about how they go through the whole process. They say – Shall we focus on 17th-century portraiture? Shall we focus on African masks? They have these series. And then they say – We collect all sorts of examples, and we feed it into the network, and we see what comes out, and if we don’t like what comes out, we change what we feed into it. Or, we weigh things, we select things, we steer the output; but from all the output there’s a lot of stuff that’s not interesting, so we select out the ones that are interesting, and that’s what we turn into our artworks – to exhibit and hopefully to sell. That’s the process they describe. If you read the websites of the auction house, they describe it completely differently – This was created by AI! The auction house is implying that this was created by an AI network with no human intervention! Well, if there had not been any human intervention, then the network would not have existed in the first place. And it certainly would not have chosen 17th-century portraiture as its subject matter, and it would not have painted that painting, because it doesn’t really give a damn whether it looks like a human or not. So, I think, at some level that huge sale was a total PR coup. But the whole area of AI art is continuing, and people are certainly getting commissions. I don’t know if they’re selling; some work is being sold and going into museum collections, but on a more sane level, the art world is saying – OK, AI is a tool that artists can use, and they can use it to make some sort of images, or they can all use the same tools in slightly different ways and produce very different things. So, you know, it’s being sorted out right now – what is it that is really interesting in AI art. Is it interesting that everyone produces images that look exactly like the ones that Obvious did? I don’t think so. But it’s another tool just like a video camera is a tool, and a paintbrush is a tool, and a pencil is a tool.

Is there anything that scares you or that you’re worried about in the predictable development of AI? Or, more broadly, in the fusion of our lives with technology?

Definitely, very much so. Technology saves you time and money, so if it’s cheaper to use an AI process rather than having a bunch of humans sitting around, then yes, the companies do that. But there is a problem of inherent bias that computers have. If we have a group of wealthy white men of a certain class, then it’s much more likely that they will feel comfortable dealing with other wealthy white men of the same class and culture. You can’t get diversity if you only have this closed group because they’re going to always replicate themselves. The problem is that when we create some sort of AI tool or any sort of technological tool that also replicates the same biases… You know, we can go in and talk to, for instance, the Secretary of State and say – I think that you have a bias, and it’s creating policies that are hurting people. But if all the decisions are made by some scientifically constructed program that everyone believes because it was scientifically constructed, then who do you make responsible?

This has been observed, too, right?

Yes. And a young woman I know who had just graduated from college in the U.S. told me recently – I just graduated from college, and I got this job with the social services department in the U.S., and they said – OK, we want you to write a deep learning program that decides which immigrant children should be taken away from their parents and given to foster homes. And she said – I’m not going to do that! Because what do I know, and what information are you using to, essentially, completely change the life of this kid and their parents? And how are you going to implement that? When the decision pops out at the other end and it is passed on to the social workers, who then march into the house and take the kid away from their parents – what’s the chain of responsibility here, how do the decisions get reviewed? So, she said – No, I won’t do that. Of course, they then gave the job to someone else. But that was just a really shocking example at a very, very important level that can completely change a child’s life forever. You know, with no soul-searching within this company about whether we should even be doing this, or should we instead be working with ethics boards to come up with such programs. No, they just gave it to a new hire. You know – Go and do this. Write a program that will decide the fate of this child. All these children. That’s what worries me.

My last question will be on quite a different topic. Your website states that you “explore the interplay of place, space, the body and cultural memory”. How would you define the difference between the concepts of “space” and “place”?

My father, Philip Thiel, was an architect and urban planner whose specific area of interest was the perception of your environment as you move through it, be it a building or an urban environment. He defines space as being an abstract concept. Right now I’ve got an object in front of me, a monitor, which is essentially a focus of my attention. Behind that there is a wall that keeps me from seeing anything that’s on the other side of that wall. There are other walls to my left, to my right, behind me – I’m surrounded by them. There’s a door here, a door there, and a window here. The window is kind of a screen – I can see through it, but I cannot walk through it. (Besides the fact that I’m three floors up and I would fall and die.) The door is an object I can open and then walk into the next space – but I can’t see through it if it is closed. And there’s the ceiling above, otherwise it would be raining and cold, and a floor below, otherwise I would fall to the ground. So, these objects, surfaces and screens are defining the space that I’m sitting in right now. If I would knock out this whole wall that has a window in it, I would have a very different space. But what makes it a place? You know, many people have lived and died in this room. I actually know that the previous occupant died here. So, what makes it a place – at least for me, when I moved into this apartment? I brought my bed covers, my Venice flag I’ve had since my last show there, and all my clothes, and I set up all of these objects here to create a certain place within the space. The previous occupant had different things, so for them it was a different place. I could put a dining room table here – I could turn this into a dining room. Then it would be a different place. So that’s the difference that, building on my father’s work, I make between kind of a physically abstract space that speaks to me as a human being – the roof and the walls offer me shelter, the windows allow me an expansive view into a larger world, a door offers me a possibility of entering a different world. But if there were bars in front of them, it would be a prison. It would be a different place, even though it’s exactly the same space. But now it’s filled with my own objects, it’s my bedroom/office, so it’s a place of refuge rather than being a prison, rather than being someone else’s house or place.