Creativity remains human

An interview with Hugo Caselles-Dupré of the Paris-based AI art collective Obvious

In the fall of 2018, a portrait named “Edmond De Belamy” was sold at Christie’s auction house for 432 000 dollars. At first glance, neither a very exceptional painting nor a record-setting sell. But what made this event peculiar was that “Edmond De Belamy” was not technically painted by a human – it was a work of an algorithm. While Artificial Intelligence had been a tool and a subject of artistic creation and reflection for decades, this became the first time a work “created” by an AI conquered the art market. The occasion caused an uproar in the press, and was covered by Arterritory as well.

The people behind the computer that painted the portrait of Edmond Belamy – a member of a fictional highborn family – is the Paris-based art and technology collective Obvious, consisting of Hugo Caselles-Dupré, Pierre Fautrel and Gauthier Vernier. They are researchers, artists and, above all, friends who explore the latest models of deep learning and the potential that Artificial Intelligence has in artistic creation. The type of algorithm that painted the aforementioned portrait (as well as portraits of other members of the “family”) is called GAN, which stands for “generative adversarial network”. In order for it to create a new image that adheres to a certain genre (in this case – portraiture), the network is being fed a large amount of existing works of the genre, which it analyzes, dissects and eventually – learns. The ongoing debate that was sparked by the 2018 sell actually just rekindles old questions that have baffled us for ages: what does it mean to be creative? Where does artistic inspiration come from? What is the status of fan artwork? And, of course – who is the author?

The portrait series of the Belamy family, as well as other works and projects by Obvious and their manifesto, is accessible on their website: obvious-art.com.

Edmond De Belamy. GANs algorithm, Inkjet printed on canvas, 70x70 cm, 2018 / © Obvious. Courtesy of Christie‘s

Why the name “Obvious”? What’s so obvious about you?

That’s a good question. When we first started Obvious about four years ago, we wanted to explore the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) algorithms to create art, and it was a bit different from what other people were doing with AI art. We wanted to have art that could speak to anybody. We wanted to have artworks that could talk to my mother or my little brother, or people that are not familiar with technology and are not expert in the field of AI. So, first, we wanted art that would be obvious to them, art that they could understand. So we thought that Obvious was a good name because we wanted to be as clear as possible. We liked the name, so it stuck.

So, you, Hugo, are the member of the trio who represents the machine-learning part. What do the other two specialize in?

Gauthier and I have the same background in art. We don’t have a proper education in it, but we are deeply perceptive to it. Our upbringing cherished our acuitivity. We don’t have a proper educational background, yet Gauthier has created music, I’ve taken painting classes, so we’ve been exposed to it. My background is in machine learning; I am a research scientist in this field, and am now actually finishing my PhD. So the expertise in this sphere comes from me, but we always make all creative decisions together. All three of our brains are what creates the art that comes out from our work. And Pierre, on the other hand, has a background in entrepreneurship.

Do you see the resounding event of “Edmond De Belamy” being sold for such a high price at Christie’s as your breakthrough, or a sort of turning point?

Yes; it was an event that allowed us to unlock a lot of discussions and a lot of contacts. Thanks to this sale, we have been able to take part in exhibitions in big museums like the Hermitage. It’s certainly something we put on our so-called artistic CV, for it allows us to be taken seriously when we talk to people who don’t really know what we do. But other than that, “Edmond De Belamy” is just one creation and not the most important or the best work of ours. But it was very important reputation-wise.

Le Marquis De Belamy. GANs algorithm, Inkjet printed on canvas, 70x70 cm, 2018

Were you surprised by how high the price went?

Yes, we sure were. We didn’t expect much when we were contacted by Christie’s; we were actually pretty scared that it would not sell at all. But we started having a lot of media attention before the auction, and then we knew that it was going to sell – at least for something. But we never thought it would go that high. We thought that, at best, it would reach 50 thousand. So we were really surprised by the result, and I think the explanation for that is the media attention and all the hype around the event. It was marked as a scandal at first – that such an artwork would be sold at a big auction house, and that might be part of the reason why it went so high – it was a moment of history. It is important if AI art is going to be a big artistic movement in the future – then, in retrospect, “Edmond De Belamy” will have been a really important piece in this project.

What was the aftermath? Did you face any hostility from the art world establishment?

We got a lot of reactions. I think what best characterizes all of them is that they were really polarized. Some were really, really good, which surely is good for us even if it’s not the truth, and some were really, really bad, which would be bad for us, but I think they are not completely truthful. I think that either way it was exaggerated because of the media attention – a very usual mechanism in today’s society. We got a lot of criticism as well, but now that it’s been more than two years since that auction, we don’t face the same type of comments. People have taken their time, I think, to understand what it was and what it meant for art. So now we get more tempered and intelligent reactions. In the heat of the moment, people tend to get carried away.

Chieko of the Catfish Bay. GANs Algorithm, Inkjet Printing on traditional Japanese Washi, 78x106 cm, 2019

During the two years since then, what new directions and major projects have you undertaken? What have you been working on?

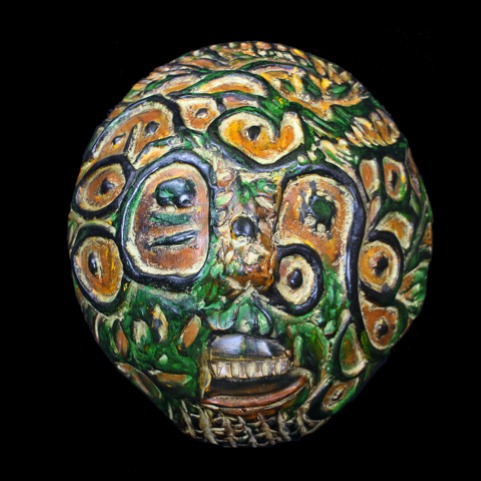

I think there are three main ways how we want to explore the use of AI in art. First, we want to continue simply making art – the series that we release each year. The year after the Bellamies we released the “Electric Dreams of Ukiyo” series. In 2020 we released a series of African masks. That’s our main artistic approach, I would say.

Another is to try to approach different types of creative industries that are more or less close to what we do. For instance, fashion is one of them – we want to explore the use of AI to create clothes. We already did a cooperative project with Nike, for example, and we are in the discussion process with other brands.

And the third way is to try to apply the AI algorithms that we use to a wider field of creative industries, like video, gastronomy, cinema, etc. It’s a bit more exploratory, because it’s not the same creative process as with creating clothes or creating art prints, but it’s something we want to continue exploring in the future.

Madame De Belamy. GANs algorithm, Inkjet printed on canvas, 70x70 cm, 2018

You use the words “creative” and “creativity” a lot, both now and in your manifesto. Do you believe that GAN is being creative, or is it you?

That’s one of the big questions that arose from the “Edmond De Belamy” sale. Now, after these two years, we do have a kind of an answer, but at that moment we didn’t have one. We quote Ian Goodfellow, the researcher who invented GANs. When asked the same question, he said that he doesn’t believe that GANs are creative, but that they can be inventive. Creativity is a property that is only referred to in the case of humans. You would not say that your dog is creative, although it can be very funny and do creative stuff. But you wouldn’t speak about your dog’s creativity; that would be a bit weird. After the same fashion, it’s weird to talk about GAN creativity, but we can talk about GAN inventiveness in the way that they invent new pictures. The real creativity comes from us, the choice of data sets, the artistic choices that we make every day. We are being creative when we decide on what to work on in particular. We are creative, but GANs can be inventive.

Does the question of authorship concern you at all? Who is the author of all this?

For now, no, it does not really concern us. The author is us, and the computer is a tool we use. But in terms of copyright and things like that, this is a very current questions that’s being asked regarding GANs. Like, how do you know on which type of data it was trained on? Many lawyers are looking at this; we are actually getting lots of requests from lawyers who are studying these types of questions in their PhD or other research. For now, it’s a really blurry question and they don’t have a final answer on it. I think we will have to wait several years before the justice system really has the tools to answer this type of question. The systems are very new and work in a very novel way, and it’s hard for the justice systems to adjust to this. It takes time. But many talented people are working on this, and I’m sure that in the next few years we’ll have an answer.

I’m sure you’re familiar with the work done by Ahmed Elgammal and his team, and the AICAN (artificial intelligence creative adversarial network) system they are using. I think what he is implying is that AICAN is actually being creative. What do you think about that? How does that differ from GAN?

It’s not that I really disagree with him – it’s a matter of the words we use and how we understand them. We sure do use the word “creative” a lot as well; it’s a matter of what sense you put into a word. Their algorithm works similarly to GANs, but in some aspect it is trying to create really novel images, and so in that sense you can call it creative, if you want; I don’t really have a problem with that. It’s just that when we said that about ourselves, there was a backlash, and in the end we preferred to stick to “inventive”. But we really understand why AICAN is named that way and where it comes from, and we don’t have a big problem with that. And it’s cool that people like him are trying to invent new methods for artistic creation. We think it’s a good development of machine learning.

So, again, what is the main defining difference between the concepts of “creative” and “inventive”?

For me, it’s the human aspect. In the end, when we looked at this subject, we see that most of the time when one talks about “creativity”, one is talking about humans. The algorithm we use is not human, so we tend not to talk about creativity for GANs, but inventiveness. In this sense, any algorithm that creates images that did not exist before is inventive. That’s where I would draw the line, but it’s always a bit blurry. You have to really play with it to understand how it works and why it’s being applied in art. But creativity applies to humans.

So if I understand correctly, creativity is something that humans possess…

A quality that humans can have, yes.

…and being creative means to be human. Sounds a bit like circular reasoning to me.

That’s a very complex question. What I would say as a scientist is that since we don’t understand how the brain works, it’s hard to talk about creativity because we cannot define it properly. As long as we don’t really understand what happens in the brain when you’re being creative, or what it is to be intelligent as a human, we’ll be talking about a blurry subject. Once we understand what happens in the brain, we will be able to compare what’s going on. But it’s a really tough and complex question, and we don’t pretend to have an answer to it. It is basically trying to define human nature. It’s a question many people have asked and no one has a satisfactory answer. You can just make an educated guess and try to extend that, but remember that other points of view might be just as valid.

Matarjio (Anticipation). GANs Algorithm, ofoton & osese wood, chalko black dust and paint. Computed in France, built in Ghana. 38x35x12 cm, 2020

Since we’re on the subject of not really knowing how the brain and the human mind works... As a mathematician and someone who’s embarked on a PhD in machine learning – do you believe that strong AI is possible?

That’s a question I’ve asked myself many times. I don’t have a crystal ball and cannot really predict the future, but I don’t think that strong AI is coming any time soon. I work in this field every day; I am also familiar with some neuroscience and how advanced we are in understanding brain activity. And we are still not very far in that regard; we don’t understand a lot of that. Because of that it’s going to be really hard to find ways to create AIs that can learn like we do. But I don’t think it’s impossible – because we exist, it’s possible. But there are many factors that impact this development. For instance, it’s investment in AI research. In the era we live in, there is a lot of investment, and it might push us closer to new levels soon, but it can also fade away really rapidly, for, as we know, there have been AI winters – periods of time when AI research has been kind of frozen. Since the 1950s there have been three of those. If another AI winter comes, we won’t make any progress. It depends on the development of research and support.

And these waves mainly depend upon investors.

Basically, yes. It’s about the business opportunities. If people will see business opportunities because of some breakthrough in AI research, then they will put money into AI research. Just like Google does, for instance, with DeepMind and Google Brain. Because there had been a breakthrough in the 2010s with deep learning, Google put a lot of money into AI research, as did Facebook, Amazon and other big companies. There has been a lot of AI research because of this money, and so a lot of breakthrough as well. Deep learning needed big GPU cards, so the market created more and more advanced GPU cards. Because of all this money, there have been a lot of breakthroughs. But if the business opportunities disappear and the deep learning disappoints investors, there may be less money invested in AI research, and so less breakthrough as well. That’s kind of the way it works. But another topic is the very concept of strong AI itself, because it’s unclear what do we really mean by this – is it simply a multi-purpose learning robot that can do repetitive tasks, or is it a robot that’s more intelligent than us, that can solve really complex programming that we cannot solve? You have to define this. Will we have a multi-purpose learning robot in the next 100 years? I think so, yes. But will we have a robot that’s more intelligent than us in the next 100 years? I doubt it.

For me, a milestone would certainly be a robot, computer or whatever that is aware of itself. That, as far as I understand, is one of the main features of what we understand with “strong AI”.

Yes, but that is also very hard to define. Like, when is the moment when the robot is aware, when exactly does that occur? Does it have to have a body, or does it just have to be connected to the web, be some sort of software?

But that brings me back to the question – when you said that you don’t believe strong AI is coming any time soon, you continued to explain this by the fact that we don’t really know much about the human brain.

Yes, for me that’s the main issue.

But achieving strong AI does not necessarily mean mimicking the human brain or artificially creating something similar to it. It might emerge from something completely different. Or may it not?

For me, the problem is that we want something to emerge out of thin air, and we don’t really understand how it emerged in the first place. We want something that we don’t understand to happen. And for me that’s a bit weird because what we do as humans when we develop technologies is that we understand stuff, and then, because we understand something, technology can progress. For instance, we understand the laws of gravity and acceleration, and so we are able to build rockets that can go to the Moon. If we would want intelligence to emerge, we would need to understand how it emerges in humans, because that is our only example. The understanding part is really crucial, because when you actually build stuff in science, you need to have ideas, intuitions, which you have precisely because you understand stuff. It’s a bit weird to be doing something you don’t understand – that’s the paradox of doing AI research. We are still trying, but that’s something that really blocks us from creating AI – not understanding the human brain. If we totally understood the brain, we would already have pretty advanced AI, I think.

Making a network that creates works in portraiture or creates fashion is one thing, because those are genres with a list of set rules. But do you think it’s possible that sooner or later AI would be capable of creating conceptual art? Not something that mimics classical plastic art genres, but that expresses itself conceptually.

If we achieved that, we would be very close to what we mean by strong AI. Because the action of creating something out of oneself, to be proactive in a way of wanting to create something totally new and creative, is something that humans do, but we don’t really know why and we don’t understand how it works. So, for me, for an AI to be that advanced would require lots of algorithms that we have now, and more algorithms that we don’t have. What would such and AI work on, and would it have to have experienced something or be fed lots and lots of topics in order to combine them and find new ways to arrange topics…? It’s a really different approach from the tool approach that we use now, and that would be something really exciting, I think. For now, we don’t really have the algorithms to do that. I think this question is close to the question of whether one day we will have a strong AI.

But no matter how many algorithms or knowledge we fed the network, still, it would go on and create the work only whenever we push the button or otherwise make it do it. But what could create an incentive or motivation in the network or computer to do it by itself at a random moment? Can you imagine that?

Yes, I can. You would have to design an algorithm that has an aim to do just that. When you push the button, it should start looking for topics to work on, and then find ways to create by itself. We might incorporate such creative processes into the algorithm, but that requires an algorithm design that we don’t really have now. We would have to find ways to create algorithms that do just that. We know that we, as humans, have a heritage of millions of years of evolution behind us, so we do start with some knowledge of the world already, right when we are born. We know how to signal hunger – we cry because we know that our parents will come and feed us, and things like that, but our creative process is mainly motivated by all the experience that we receive from the world, so we would have to design algorithms that are fed lots and lots of stuff, just as we are fed lots and lots of stuff in our lives. We want to do something creative because of everything that we have seen in our lives. And so the algorithm would have to work in the same way – it would have to experience different types of data and then, based on this data, it would need a mechanism to trigger an incentive to create once it has seen different stuff that might go together, and do something aesthetically pleasing, for instance. That’s the only way I see that we can create algorithms that create on their own.

In your work and also in the manifesto of Obvious, the way you profess combining the latest machine learning with human creativity sounds thoroughly optimistic. But are there any possible unpleasant AI scenarios that worry you? – Both within the arts and in the development of AI as such.

Yes, we really try to tell about and showcase the good use of AI as much as possible. We don’t like falling into stories of AI controlling us and so on. Why not? I think there is already a large body of work and people that are working on and studying the possible harms of AI in our society and in art. I think it’s something very natural for us to be scared of this and to try to see the negative factors and the things that won’t work – things that could harm us. In our approach we are very aware of all the problems that could arise from the development of AI in art or in society in general, but we really try to showcase the good examples because we don’t think that enough people talk about it. Because of all the science fiction work that we have – by Philip K. Dick, Asimov and others – we are already fed this narrative that AI is bad, and so that’s why we try to give the narrative that AI can also be good. Many other researchers are also doing this because many of them are building tools that can help people – that can cure diseases, for instance. But yes, in our work we really try to maintain a positive focus and not give a dystopian view. We try to show that yes, it’s possible to use AI for good and use it for creation.

What do you mean when you, on your website, use that Picasso quote and evidently disagree with it? That “computers are useless, they can only give answers”. And you add “well, Picasso, it’s a disagreement”. What do you mean by that?

It’s kind of meant to illustrate this narrow view of technology. There is this pejorative view of technology, I would say, among many people, that computers are not as good as us; we are always trying to compare ourselves to all the technology that we live alongside with – especially AI, because it is trying to automate things that humans do. We don’t believe that computers can only give answers. They can also ask questions. Our work was created with AI and received a lot of questions, and it was actually a really healthy debate, one that we think is interesting to have and that can push all of us forward. We don’t view technology as just something that is laying around and that we can dismiss. It’s something that’s part of our society and even a part of human nature, and so we really have to talk about it and use it in ways to better understand it; I think most of the fear around AI comes from the fact that people don’t really know much about AI – what it really is, what it is today, what it can do, and how we can use it. If you understand it well, you can see that it’s better to approach both the shortcomings and the advantages.

AI-designed Nike sneakers

What are one or two of the most idealistic and most important goals that Obvious has projected in its future? What would you like to do or achieve, and what are the reasons you are doing what you are doing?

One of the big reasons why we do what we do (and it is one of our biggest goals and not something that we can personally achieve) is that we would love for AI art to become a real artistic movement that is going to be the highlight of an era. If AI art would become the most important artistic moment in the 21st century, that would be the biggest goal that we could achieve – for this type of tool to be used in a creative way, and to be really useful for people and create lots of different stuff that people can enjoy. So that’s one of our biggest goals, but it doesn’t really depend on us; it depends on how people approach the technology and whether they really want to use it in art. Of course, it also depends on the development of AI research. It depends on a lot of stuff, but that is our ultimate goal. More realistically speaking, one of the things that we would really like to do as a collective is a fashion creation that would be interesting for an existing brand. That’s something we already did with Nike, but we would like to push it a bit further. That’s a project that we would really want to see become a reality in the next few years. We would like to develop the use of AI in fashion because it’s really suited for this type of field, and it can create interesting fashion items – especially sneakers. We already have models that look promising, and we would love to make them for real.

Ok, Hugo! Thank you very much!

Thank you!

Title image: Obvious / From the left: Gauthier Vernier, Hugo Caselles-Dupré, Pierre Fautrel