In the middle of the river, you see things that you usually can't

A conversation with finalists for the the 2021 Purvītis Prize, artists Reinis and Krista Dzudzilo

Reinis and Krista Dzudzilo are artists who mostly work as a duo – creating set design for theatre and opera productions, as well as installations and objects that correspond to the classical language of contemporary art. There are a few departures, such as Krista’s painting, but usually when one hears the name Dzudzilo, both spouses come to mind.

Essential features of their signature style are perfection, polished minimalism, attention to detail, symbolism, and a strong conceptual narrative. But likely their most important talent is the ability to see a space in its entirety, sense its potential, and using seemingly common and standard codes, provide the viewer with a fascinating artistic experience that connects the present with the past, and the current with the ancient (the viewer is important to them as both a conversational partner and as a character that is part of the artwork). ‘In the theatre, we are told that we are too visual, while in the visual art world – that we are too theatrical,’ the pair commented during the interview, adding that they believe in interdisciplinarity and think that the most powerful tool in art is the synergy between different fields. Their work is a testament to this conviction. Many of their pieces are based on the interplay between genres, and music is often the most prominent of these. In a way, it has become the core of their art and the centre of several of their projects, all of which could be described as balancing on the borders that separate theatre, performance art, musical concerts, and the visual arts.

Music is also at the centre of the work ZRwhdZ – in 2019 this large-format installation (essentially a gigantic music box) was exhibited at the Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space, and in the autumn of the same year at the Kim? Centre for Contemporary Art in Riga. Now it has been nominated for the 2021 Purvītis Prize (the exhibition presenting the works of the nominees for the award will be on view in the Great Hall of the Latvian National Museum of Art beginning 4 June 2021). ‘ZRwhdZ is like a formula. It's like the golden ratio that can be used to approach the ideal of living art. The title of the work, which stands for ‘Zum Raum hier wird die Zeit’ (Here Time Becomes Space) comes from Richard Wagner's last opera, Parsifal. These two pillars – Time and Space – are the legs on which scenography moves. While on a trip several years ago, we bought a pocket-sized music box that fit in a person’s hand. But a person can also fit inside a music box. Something can arise between the contradiction or ambivalence containing immaturity and its loss, or even its recovery. Art raises questions because in creating it, the world must be rediscovered from anew.’

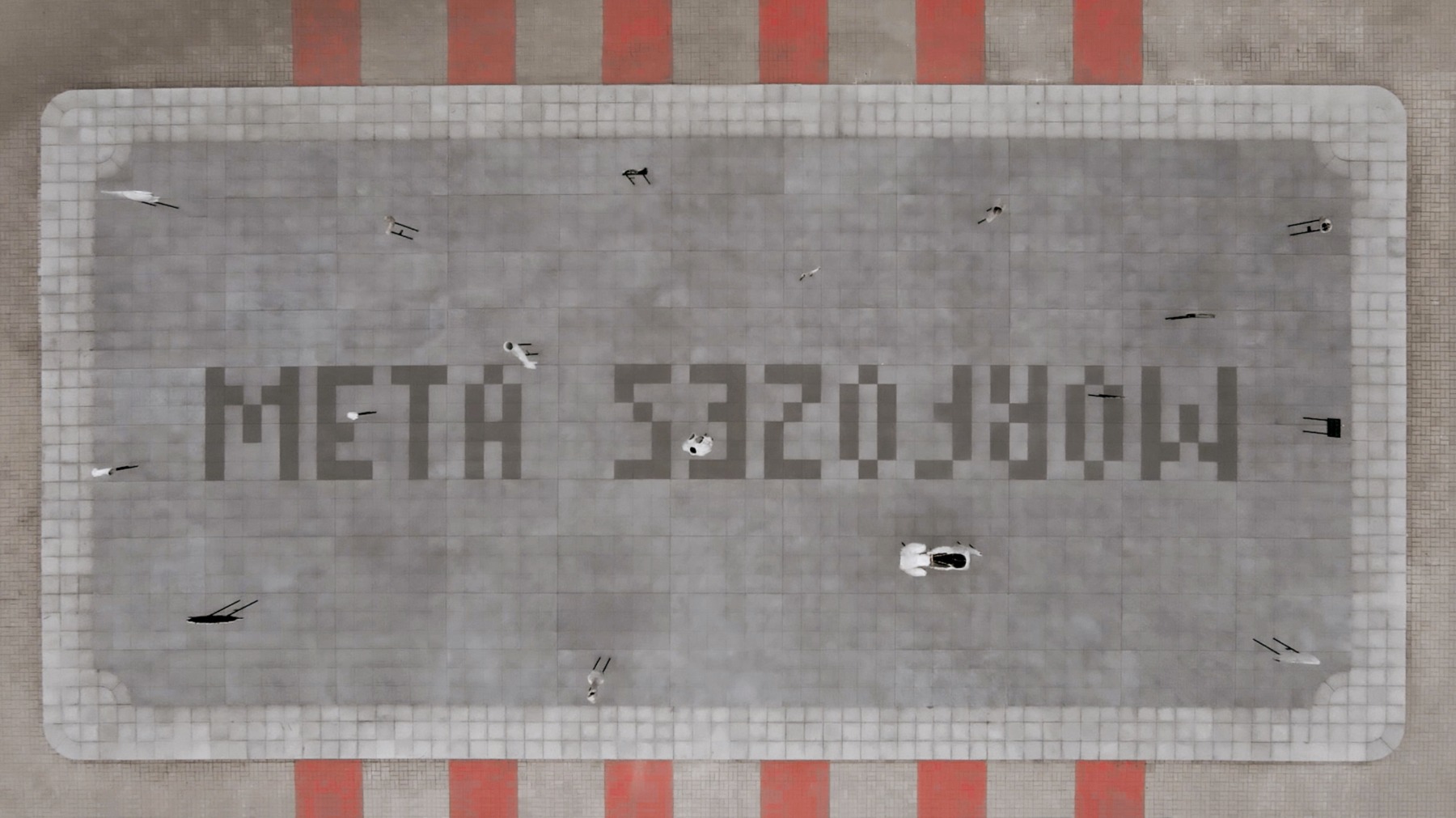

Krista&Reinis Dzudzilo. Metamorphosis. 2020/2021. Photo: © Jānis Ķeris

The past year of the pandemic has been surprisingly full for Krista and Reinis Dzudzilo: their concert performance One will take place at the Ventspils Concert Hall this summer; in autumn they’ll be holding their solo exhibition ALMA MATER at Alma gallery in Riga; and this past November, their large-format environmental object Metamorphoses (which is still on view) was unveiled in the square near the Latvian National Opera. Not to mention the duo’s collaboration with movement artists Elīna Gediņa and Rūdolfs Gediņš on the production Very Good Minutes, about the relationship between Asja Lācis and Walter Benjamin; it is to be presented on the Large Stage of the Dailes Theatre, and will hopefully be seen by audiences in the near future. In addition, the Dzudzilos, in cooperation with the Latvian Literature team (an export platform for Latvian literature) and Una Rozenbauma (the author of the #iamintrovert campaign) have created the object In3 or Introvert In Interior, which will be representing Latvia at this year's London Design Biennale.

How are things going for you during the pandemic?

Reinis Dzudzilo: It's been almost a year. Everything is the same and everything is not the same; a lot has changed externally, but at the same time, internally it’s been constant. In terms of work, the first half of last year was very calm – after the theatrical piece we did in January at the Liepāja Theatre, Century of Indifference, we returned to our studio, which is where we like to be, work and think. In February, Krista’s Through a Glass Darkly still managed to open, but then with the onset of the pandemic we just completely holed up in our studio. The nearest engagements we had planned were to take place in the autumn, so we were able to work quietly. We’re working on a new work, Tagadne (Present), which will hopefully be presented in August of this year at Hansas Perons. It embodies the way we want to operate; it’s a four-part work in time. We hope that we will be able to turn this time-space moment into an arrow that can fly and, eventually, hit its mark. Nevertheless, after the peaceful first half of 2020, many unforeseen events and activities happened.

Krista&Reinis Dzudzilo. ZRwhdZ. Riga. 2019. Photo: © Ansis Starks

Krista&Reinis Dzudzilo. ZRwhdZ. Riga. 2019. Photo: © Ansis Starks

Krista Dzudzilo: Present has come a long way. Meeting Krists Auznieks was serendipitous. You can't plan the most important events in your life; they happen to you – wrote Rob Riemen. The moment we heard Krists’ Fire and Rose, we wanted to make this piece our own, immerse ourselves in it and just be. Of course, this is also a kind of egoism. And now it has indeed directly become a part of our work and life. We have chosen a career path in which we do work that is personally important to us. That is why 2019, which is when we represented Latvia at the Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space, was completely quiet for us besides this one work. To some extent we reorganised our entire lives for ZRwhdZ, which was shown in Prague and then at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre in Riga.

Krista&Reinis Dzudzilo. ZRwhdZ. Riga. 2019. Photo: © Ansis Starks

Interdisciplinarity is your foundation – you regularly work in theatres, opera houses and concert halls; you work closely with musicians, directors and actors; there are often many people involved in creating your work, even when they are distinct works of visual art on display in a gallery or urban setting. How important is the role of ideological synergy, and all other types of synergy, in your art? What is the substructure that holds everything up?

K.Dz.: It is essential to be aware that it is very important for the various areas to talk to each other. For example, art and music.

R.Dz.: At the base is a ritual, and that is very vital. Like any [religious] mass that seemingly always deals with the same thing, but you're invited to experience it now and definitively. This synergy, or becoming one, is one of the most beautiful acts that can take place. Transformation into ‘one’.

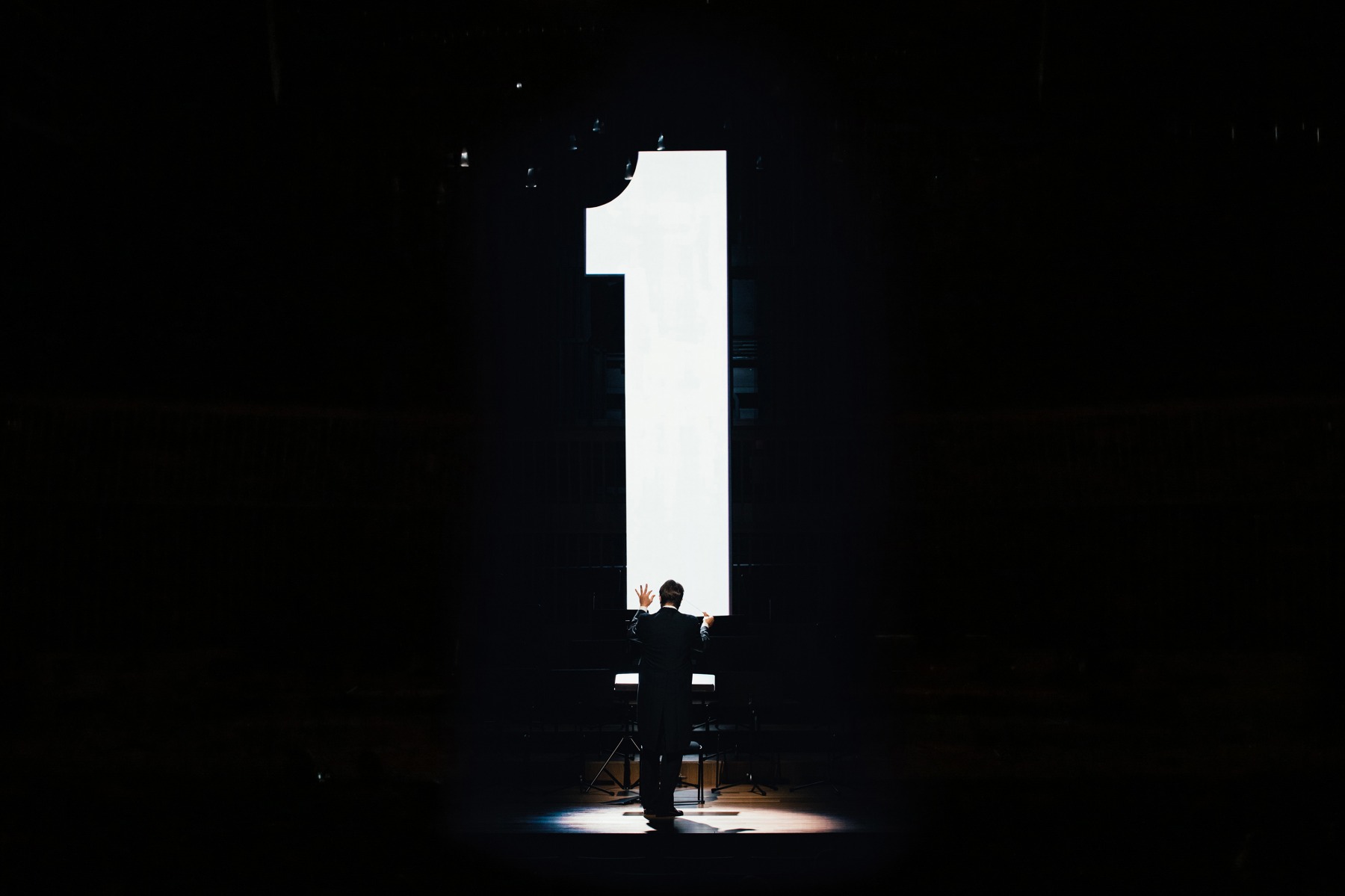

Concert performance "One" / Darius Milhaud, The Six Little Symphonies / Ventspils Concert Hall / Photo © Kristaps Anškens © Dzudzilo

K.Dz.: You can rediscover something or immerse yourself realising that, formally, nothing new may come of it. It can be reassuring to see or experience something new in something that has been there from the beginning. Our works are often created with the involvement of many people. They are made by other people's hands or by other people's bodies. For example, the concert performance One at Ventspils Concert Hall in which, from the point of view of visuality, not much was physically created from anew – just a five-metre-tall numeral ‘1’. It is the event itself – the presence of living people in a space that has its own architecture, and the music, which was divided into its primary elements only to eventually reunite, and the movement of the spectators and their attitudes towards what they see and hear – that becomes an object of art. It was a beautiful and multi-voiced dialogue that became an unexpectedly meaningful event for us.

Concert performance "One" / Darius Milhaud, The Six Little Symphonies / Ventspils Concert Hall / Photo © Kristaps Anškens © Dzudzilo

R.Dz.: It reveals that conversation is also formed through form and viewing. To see and understand something, you don't have to recreate what is to be seen. In other words, you are always creating that which will be seen, but that doesn’t mean it must always materialise as a new object.

Is the space a part of your artwork?

R.Dz.: Yes, it is an integral part of the work. Perhaps even the most important part. Because it both opens the work and shapes it; it’s what allows you to see it.

When I was going to the Jānis Rozentāls Art High School but lived on the opposite side of the Daugava River, in winter, when the river would freeze over, I would sometimes walk across it. And when you’re in the middle of the river, because of the new space you’re in, you see things that you usually can't. You’re seeing another city, but as Krista says, the same one that has always been there.

K.Dz.: Art provides the opportunity to be in a different reality. To create a space that invites contemplation. The reality of art is something completely different from everyday reality. That is why we often have objections to attempts at directly showing everyday reality. Honestly, it’s not even possible – it is always a created reality.

R.Dz.: A created space of reality that stops when it ceases to be observed. It does not exist without a viewer.

K.Dz.: We’ve talked a lot about the fact that works are destroyed, but this is a common thing in the theatre. It is sad but, at the same time, natural that you are here, you’re creating something, it’s important to someone, and then it is no more. You leave the space and you don't know if it continues to exist without you. To some extent this may be related to the fear of death, or to not understanding it, but it does make you accustomed to the fact that it is natural for something to end.

Krista&Reinis Dzudzilo. ZRwhdZ. Riga. 2019. Photo: © Ansis Starks

Through the ‘death’ of your work, have you come closer to your personal understanding of death?

K.Dz.: Every day brings us closer to our own death, but do we understand any better... At times, and for a brief moment, it seems that something is understood, but then this eternal, independent unknowing returns. Rather, the death of works shows how calm and harmonious everything continues to be even after something has physically ceased to be. What remains then is the memory of the place – memory as a personal thought process – and then that too becomes fainter. Everything comes to an end, yet everything continues to move on. Here I could mention Gandelsman’s reference to Zeno's paradox about the arrow that flies and, at the same time, does not move – the arrow is flying forward but, at any given moment, it is standing still. That’s beautiful! This was also one of the themes we were thinking about when creating ZrwhdZ.

R.Dz.: As you said this, I visually imagined how movement remains in one’s memory. Death stops the possibility of creating new movement, but ‘life’ is still soars in the memory. You know, maybe it is through the birth of works that we have come closer to understanding death.

Krista&Reinis Dzudzilo. ZRwhdZ. Riga. 2019. Photo: © Ansis Starks

A significant trait of your creative expression is the presence of music.

R.Dz.: Music has always been very dear to Krista. It was different with me. Before I met Krista, I definitely didn’t listen to music as much as I do now.

K.Dz.: Music is extremely important to me. I used to reproach my mother about not giving me a musical education. When I was old enough to understand the deficiency of music in my life, I realised that the opportunity to become a professional musician had already passed.

R.Dz.: And you didn't want to be an amateur musician...

K.Dz.: Absolutely not. I remember how in 4th-grade music class we were taught to recognise various very famous and well-known compositions. I thought that once I could recognise all of the classical music works, I would become a real person. It was only later that it became clear to me that this would never be possible. But I started to seriously listen to classical music at this age. Music became the absolute art form for me. Its meaning is fundamental in my life.

Reinis mentioned that you, Krista, definitely did not want to be an amateur. This obsession with perfectionism seems to continue into your art.

R.Dz.: Yes, definitely. It is probably related to some trauma of Krista’s, as well as mine. Perhaps not necessarily trauma, but experience. It’s a way to deal with the world and organise it, understand it. To near the ideal. Whatever you call it – let's call it the golden ratio, the truth – and move towards it. It is clear that completeness already exists in forms that are not always perfect, but perfection of form is essential to us. Unfortunately, I didn’t have much chance to talk to my grandparents, who passed away quite early. My grandmother was completely deaf, while my grandfather was hard of hearing, nearly deaf. All three of their children, my mother and her two brothers, were born hearing. I am convinced that this has affected me in the second generation as well, and that it is my legacy – the lack of one sense causes one to concentrate and pay more attention to another sense. I think that’s where my greater focus on the visible world, visuality, and visual order comes from.

K.Dz.: It is interesting that similarly both of my parents worked in a school for the deaf, and I spent my childhood with deaf children. Visual dominance has played a very important role in both of our childhoods. We both experienced TV without sound and only with the images. Proportion, movement, colour and montage are dominant. Humans have an almost uncontrollable desire to attach themselves to the story they are hearing; there is a desire to follow the words, but in the same way you can follow the visuals that are not based on the story but on a change, or no change, in the images. You can look at one red area that is moving and really see that movement as something surprising or suggestive. It can be even more interesting than any sound.

R.Dz.: Or, you can stop the movement, stop the narrative, and create emptiness. To do that, you must be a perfectionist.

K.Dz.: Perfectionism (but not pedantry) and an inclination to do your job as well as possible does not mean that there are no coincidences. Especially when living people, performers and viewers are involved. Accidents and life will happen, regardless of whether planned or not. Artificial coincidences are not compelling – that would be like predicting that a person will breathe in air – it’s going to happen whether you plan it or not. But what is interesting is to create the conditions that invite a person at a specific moment to see, feel and understand that they are breathing air. This perfectionism we’re talking about is perhaps like a ‘podium’ on which one can see and experience chance. And there is no need for doubt – it will happen.

R.Dz.: This pursuit of completeness can be compared to architecture. You are both told and not told how to navigate through a structure. But it must be entered, and it is important for us that the beginning and end of a work lead the viewer both in and then out.

Performance "Pathetique. On Visible Language" during the Homo Novus theatre festival in 2017. Idea and artistic realisation: Krista Dzudzilo&Reinis Dzudzilo. Photo: © Didzis Grozds © Andrejs Strokins

Performance "Pathetique. On Visible Language" during the Homo Novus theatre festival in 2017. Idea and artistic realisation: Krista Dzudzilo&Reinis Dzudzilo. Photo: © Didzis Grozds © Andrejs Strokins

Silence and emptiness are a part of your story.

K.Dz.: A work begins with ‘clearing the slate’, with a silence that allows you to detect something, observe. It’s either a curtain, darkness, a white space, or something else, and then you can experience the beginning. The birth of something. It’s as if you’ve been given a telescope that gives you the ability to bring into closeup a specific detail in a completely physical way

R.Dz.: My mother's brother became a conductor; my sister, for her part, enrolled in the study programme for musical composition this year. We spoke to my mother's brother, who watched our performance Pathetique. On Visible Language during the Homo Novus theatre festival in 2017, after which he said that perhaps the reason for his becoming a conductor was his parents’ deafness.

K.Dz.: He remembered that in his youth he was complimented on his beautiful hand movements. Only after seeing Pathetique did he realise that this could be linked to sign language, which in the most direct sense is hand choreography that reveals language.

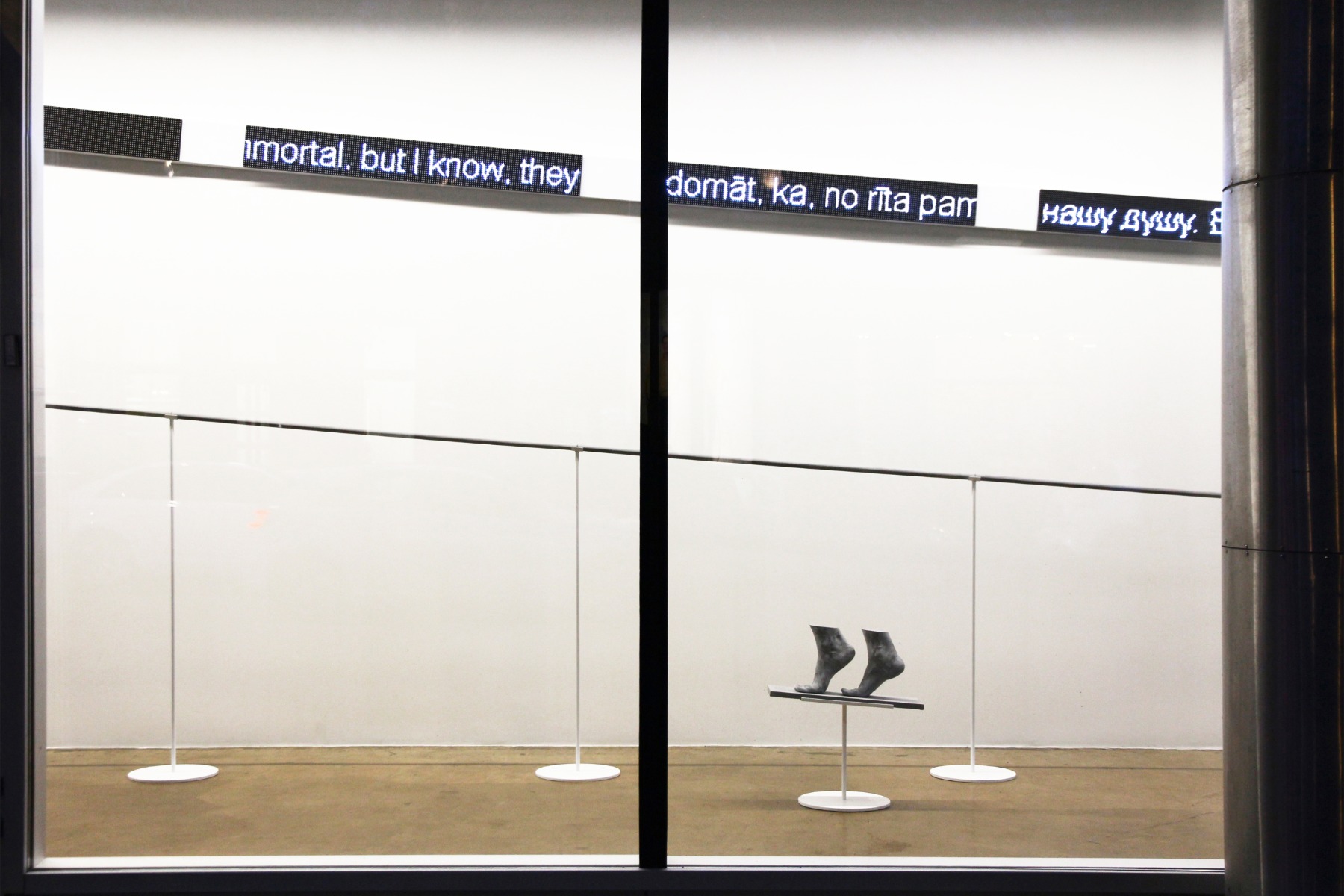

Kristas&Reinis Dzudzilo. Solo exhibition ALMA MATER at Alma gallery in Riga. 2020

One can find references, quotes – artifacts – in your art. To what extent do you both have a significant connection with the history of art and culture – with the past? Wagner, Tchaikovsky, Malevich – they may not be directly quoted, but there is a sense of their presence.

R.Dz.: Of course, one of the reasons could be school, where you go through history and through the past during the learning process. ALMA MATER at Alma gallery was also a walk through the past. As Krista often quotes: the ancient Greeks headed into death backwards. But... it's clear we're heading into death. All the time.

K.Dz.: That was more logical – that we’re heading into the future backwards. In reference to the fact that the past is always before our eyes; it has a face whereas the future is invisible, unknown.

R.Dz.: This answering of ideas, referencing, is a very interesting game.

K.Dz.: We are two who create one work of art, and we are always in conversation with each other. And yet it is a necessity to talk regardless, even if this ‘someone’ is dead, as it happens with music, the written word, or an image. The conversation is always alive because it takes place in the present. Perhaps our cultural-historical or geopolitical situation is also a reason for that, but I definitely have a desire to listen to the voice of the past (as well as the present). When we were in residence in Paris, something fanatical woke up in us. We decided that we wanted to spend a lot of time in the Louvre. On our seventh visit, after having been there for five hours by then, a strange and at the same time invigorating feeling came over us. We realised that the artists who created these works are somehow with us; that direct conversation is possible outside of this particular time.

Kristas&Reinis Dzudzilo. Solo exhibition ALMA MATER at Alma gallery in Riga. 2020

But aren't you afraid of repetition – of, in a completely unconscious way, making your own art into a kind of banality?

R.Dz.: No. We’ve already talked about it – banality. The stars themselves are not banal, but a person or their interpretation of the stars can make them banal. In this sense, the structure of a year is also banal – it constantly repeats the four-season cycle. We have worked a lot in theatre, and we will probably continue to do so, but certainly not as much. But at the same time, perhaps even more but in a different way. We are gradually approaching this goal.

Why do you want to move away from theatre?

R.Dz.: We want to go beyond the theatre in which we have been working up to now.

K.Dz.: In fact, we have been moving towards this for a long time. We’ve been having a conversation about the visual arts and theatre for more than ten years now, and it’s not over. At what moment does something overlap, at what moment does something begin and end; when can we talk only about theatre, and when can we talk about the visual arts. And since the beginning of this conversation, Reinis has always been a deep ‘believer in theatre’ and has tried to convince me. On the other hand, I am always in favour of the visual arts and remind him that we are visual artists even when we work in theatre. Creating works for the theatre is an opportunity to look for this point of contact at which the conventional form of theatre meets the visual arts. That is what interests us. Undeniably, most of our work in theatre has been adjacent to the existing form of dramatic theatre, but we have always remained true to our convictions. Nevertheless, we are increasingly realising that in order to be true, we need to talk about what we are most directly interested in. In this regard, the already mentioned visual theatre performance of Pathetique. On Visible Language was important.

Performance "Pathetique. On Visible Language" during the Homo Novus theatre festival in 2017. Idea and artistic realisation: Krista Dzudzilo&Reinis Dzudzilo. Photo: © Didzis Grozds © Andrejs Strokins

Do you wish that scenography was just as important a component as the story or the characters?

K.Dz.: I don't even know if it's especially important to think about which component is the most essential. The work and the work’s relationship with the viewer are what is important; which component is at the forefront at some point is not the deciding factor. Yes, the most crucial thing is that the conversation in the foreground.

R.Dz.: There is no separation. It is a universe.

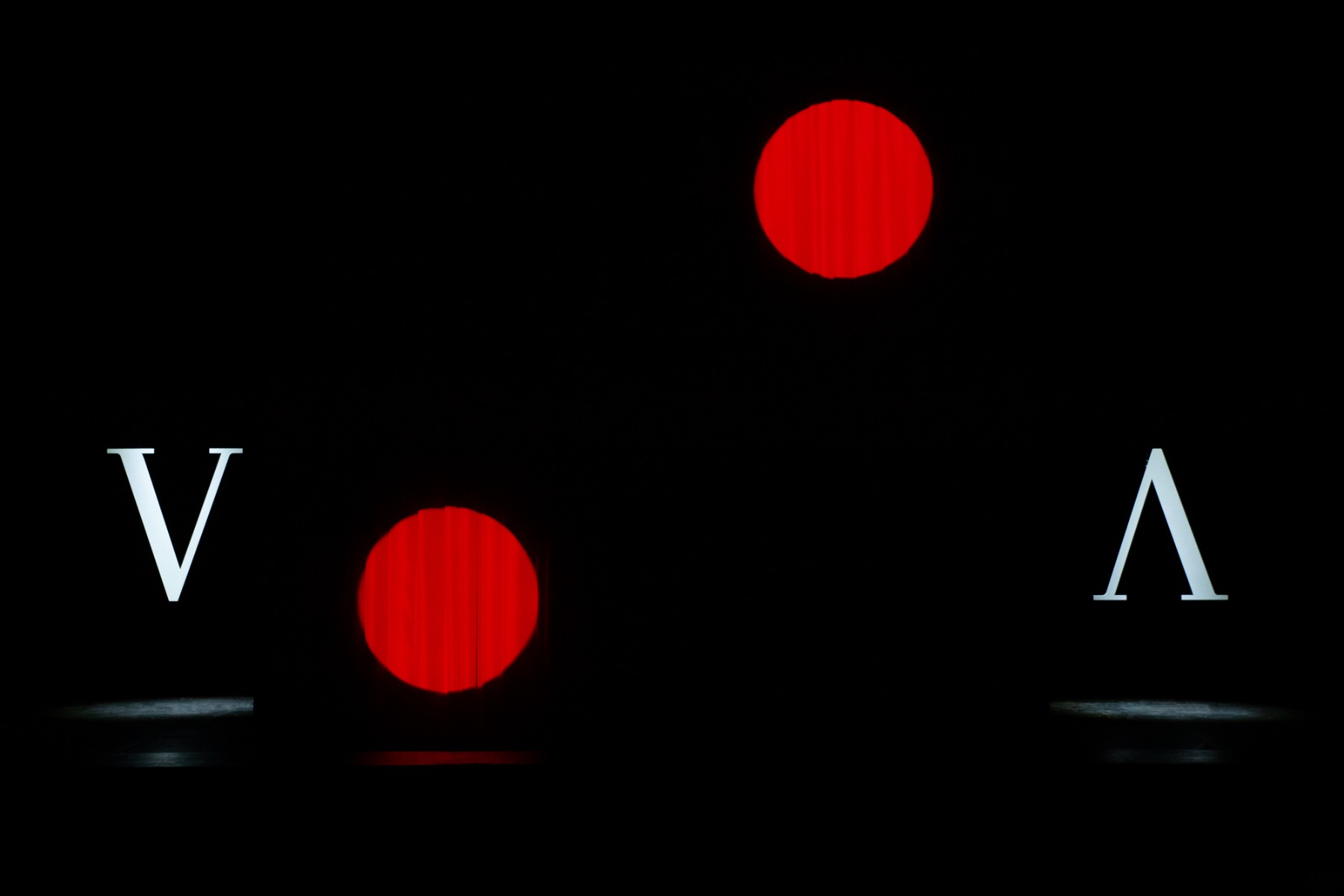

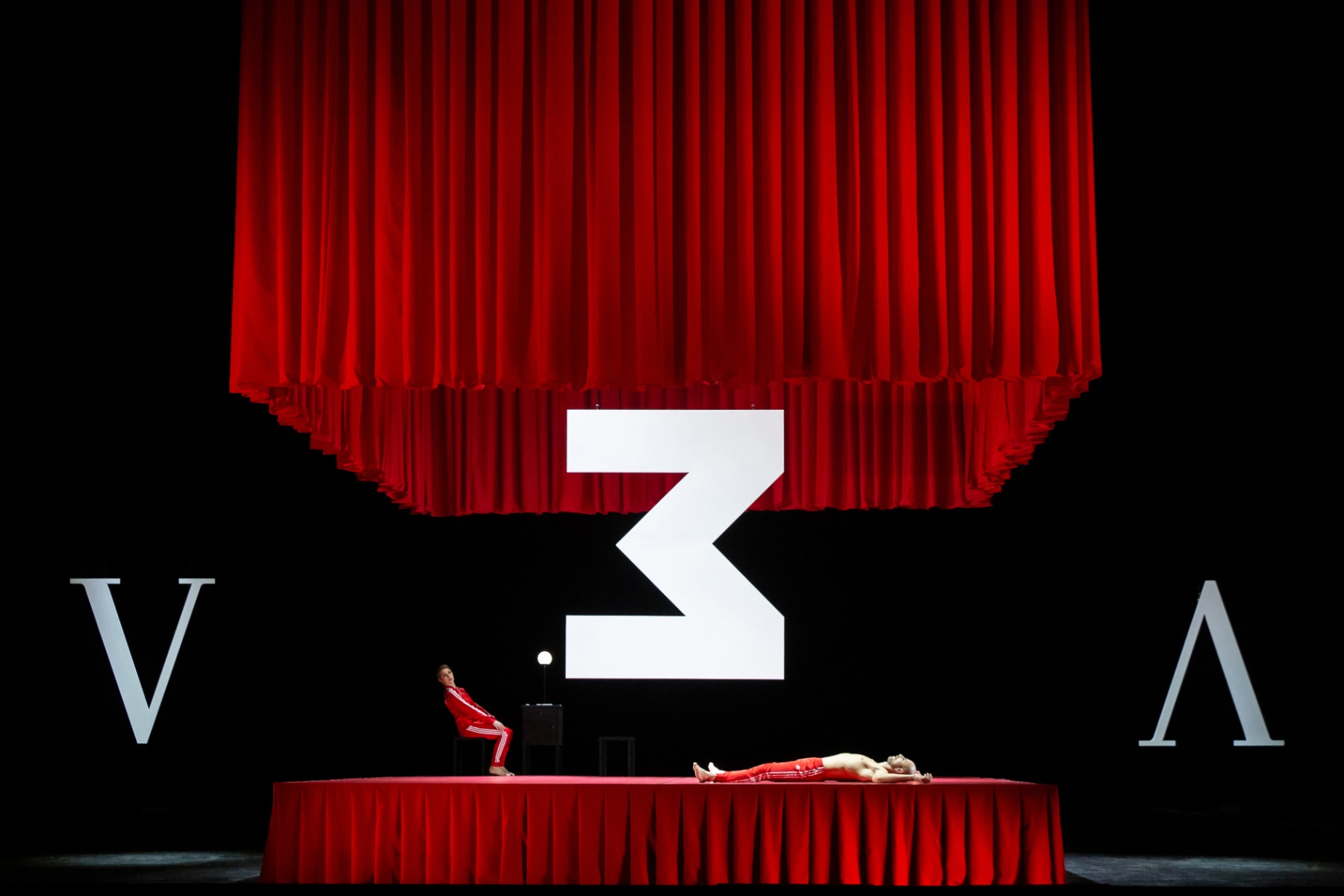

Production “Very Good Minutes”, about the relationship between Asja Lācis and Walter Benjamin / created in collaboration with movement artists Elīna Gediņa and Rūdolfs Gediņš / on the Large Stage of the Dailes Theatre, 2020. Photo: © Agnese Zeltiņa

Your latest show, Very Good Minutes, about the relationship between Asja Lācis and Walter Benjamin, was created in collaboration with movement artists Elīna Gediņa and Rūdolfs Gediņš [due to the pandemic it has not yet been performed in front of an audience]. It has been described as a conversation between movement artistry and the visual arts, and in it you use your familiar set of tools – perfection, minimalism, and a kind of absolute beauty in the creation of which you use the same banalities already mentioned in this conversation, for example, the colour red. They are codes that are easy to read but simultaneously become energetically dense in a given context.

K.Dz.: Very Good Minutes is a very good example of a conversation between us and the choreographers and performers. In this case, they created the movement material [choreography] before we started thinking about what it might look like. We spoke, one could say, to the material they had created, which is a subtle, beautiful, and bodily filled intellectualism, and we felt that it should be treated as an artifact, as an object of art to be exhibited – in this case, not in a white cube but in a red one. In the context of this performance there are also several important aspects related to contemporary dance as well as to visual theatre: respectively, reflections on the venue of such a performance in the Latvian theatre scene. That is why the colour red is significant – because contemporary dance does not have access to this banality, the red velvet curtain that is so common in theatres. Dance and visual theatre are mostly consigned to a peripheral space, or they can only be found in decidedly non-commercial projects. The venue for this performance is also important – the largest theatrical stage in Latvia.

R.Dz.: We had already agreed at the beginning that we would treat the movement material as dramaturgy. A very important part of this production was Walter Benjamin’ Moscow Diary, which gifted us with visual images. And one of these was the colour red, which marks both the time period – the beginning of the 20th century, the revolution, and the birth of the union – as well as, of course, the suprematist Malevich and the ‘square revolution’. Art is dead! Long live art! And we want to repeat that: Art is dead! Long live art! Theatre is dead! Long live theatre!

Production “Very Good Minutes”, about the relationship between Asja Lācis and Walter Benjamin / created in collaboration with movement artists Elīna Gediņa and Rūdolfs Gediņš / on the Large Stage of the Dailes Theatre, 2020. Photo: © Agnese Zeltiņa

K.Dz.: Another important thing is the interplay of words in Russian, in which the word for red, krasniy, also means beautiful. We talked amongst ourselves about many things: suprematism; geometric shapes which are themselves perfection; how the globe, which is round in shape, can become a square; at what moment can a round world turn into an angular world, and when does this angular world turn into a battlefield; when dance and bodily relationships become a form of battle. Walter’ and Asja's relationship described in the diary is based on a game that appears on stage as a passionate playing of dominoes – which are also rectangles with circles. Of course, it is a formal labyrinth, but getting lost in it and finding yourself is very interesting – both for Rūdolfs and Elīna and us two. The concept of play is extremely important in this production: What is a game that takes place between two people? Can a sexual act can become an Olympic sport? How do clothes or a naked body in motion change a character?

The element of sound is also significant in the production as a whole.

R.Dz.: Yes; both when we read the Diary and when we saw Rūdolfs’ and Elīna's movement material, it became clear to us that we had to work with audiovisual techniques in which the foundation of the sound could come from two different language branches – Germanic and Slavic. Asja and Walters communicated in those languages, as did the two occupying powers in Latvia during the last war. They are both foreign languages, but at the same time they have also been ‘local languages’.

K.Dz.: This audio pathway consisting of different words simultaneously becomes a musical score that at times forms the rhythm of the performance, or it becomes the musical pitch for the next scene.

R.Dz.: The presence of audio helps in the creating of images. But in general, I agree with and acknowledge that the most important thing in art is not ‘what’ but ‘how’.

Because the most important thing is form?

R.Dz.: Yes, for us it is definitely the primary component. And the movement of this form – even something as simple as moving from left to right. Even if you know that the ‘form’ will move from left to right, this knowledge doesn’t give you anything until you see it and experience it. It has to constantly pierce into your present. Art in the present [moment], which can be executed through an organised event at a certain time, creates this opportunity.

Is the character of the viewer important to you?

R.Dz.: Yes; the work does not exist without a viewer. If the work is shut up in a closet where it is not visible to anyone, in our opinion, it (without the viewer) does not exist.

K.Dz.: But at the same time, the works last for as long as we do.

R.Dz.: Because they are being seen?

K.Dz.: Yes.

But is the viewer of today able to see, to perceive?

R.Dz.: Yes, of course. But in my opinion, the work of art must also take responsibility. It can, of course, be arrogant towards the viewer. What matters is the extent to which the artist is interested in their work addressing or affecting the viewer.

K.Dz.: I don't know how to look at art ‘correctly’; I don't have an answer. I too react differently to works of art at different stages of my life and even at different times of the day. There definitely must be a desire to stop and listen. I have thought about how I feel when I see my works in a gallery – a space that is specially designed for exhibiting and viewing them; a space that has been built and created with the aim of being conducive to art. It is extremely interesting to think about how the body of a piece of art is built in order to function and be alive. At the same time, I feel that my paintings are too similar to the gallery space itself and that they live better outside of it – in conditions that are much ‘louder’ and where this ‘little silence’ can become a place that grabs you.

Were you able to see anything at the Louvre in the hustle and bustle of the crowds?

K.Dz.: It is a mess of art – there’s a disheartening amount of artworks there. But at the same time, by being there often, we gained peace. Like finding yourself in a kind of fog. All the works and the building itself become one entity, let's call it a fog, and then your attention is drawn to one item – a painting, or an Egyptian earring, or a detail from a column from the Roman Empire – and such an encounter can be really impressive.

R.Dz.: But at times a panic would arise from its denseness and intensity.

From the energy?

R.Dz.: Yes. In the same way that you can feel a bit ill when approaching a bookshelf: just from the amount of information that lives there and that you can come into contact with, from nearing all the characters that can be found in there – both living and dead. But the moment you pick up a book, it's…

K.Dz.: It is your existence. In the past, when our friends would visit, they would note that Reinis' desk was absolutely empty, whereas mine was covered with books. And that gives me a sense of peace – that they, the living and the dead, are around me.

R.Dz.: But I often feel that they keep asking why I’m not answering. I mean, the ones whom I haven't answered yet, the books I haven't opened. Like uninvited guests whom you like, but are not quite ready to receive today.

K.Dz.: They demand attention.