The Poetry of Structure

A conversation with Valdis Celms

Valdis Celms is a living concept, a living phenomenon. Streams of meanings and events meet to form a single codename – ‘Valdis Celms’. And these occurrences are of various layers and types. Valdis Celms is the man who designed the Riga welcome sign that has been greeting the locals and guests of the capital upon entering the city since 1980. Valdis Celms is the man who authored the renowned cultural bestseller Latvju raksts un zīmes (Latvian Patterns and Symbols, 2017) and has lately been doing important research into Baltic mythology and neopaganism. Valdis Celms is an artist who gives artist talks at the contemporary art museum Garage in Moscow. His works, his kinetic objects conceptualized in the ’70s, were unexpectedly made a reality in 2020 becoming the conversation piece of the Second Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art. It seems that this long journey of Rhythms of Life and Positron (both pieces are shortlisted for the Purvītis Prize 2021) to being materialized is no coincidence. Valdis lives and thinks long ahead of time, and bringing an idea to life can easily take 40–45 years. And this coming to life always happens to occur in the right place at the right time.

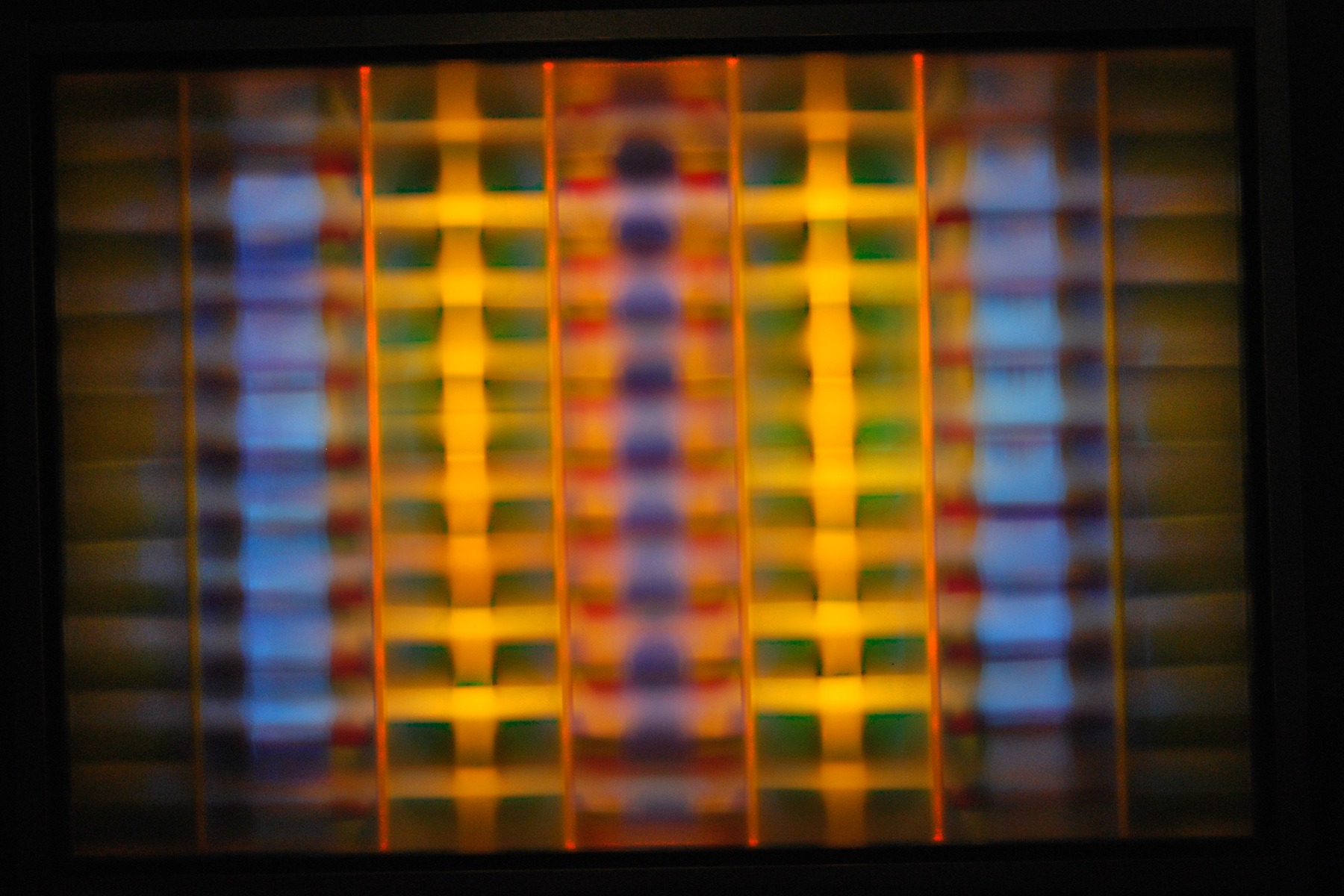

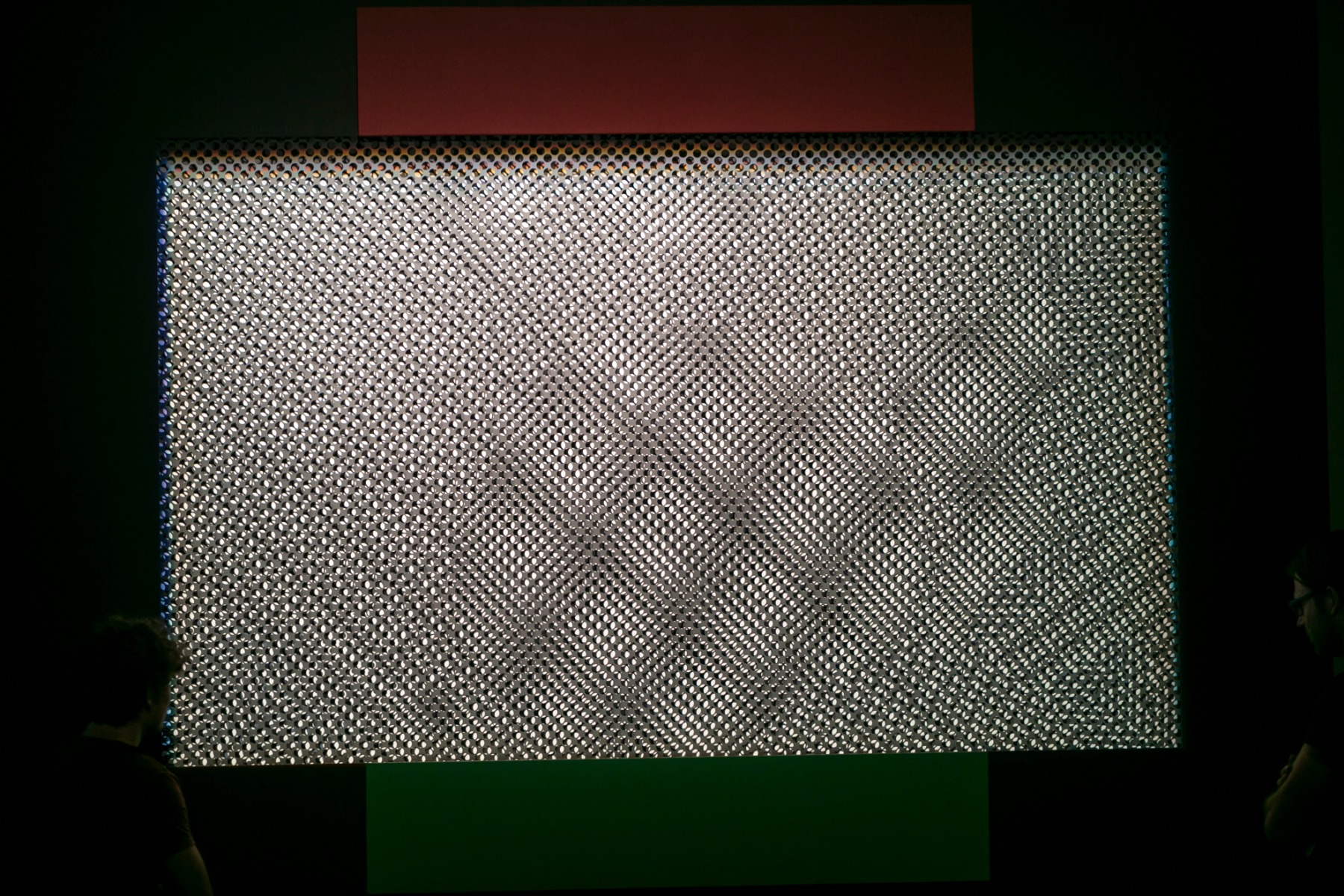

Valdis Celms. Daugava. Kinetic light screen. 1974. 105 x 155 x 35 cm

In 1961, he graduated from the Riga Technical College for Construction and in 1970 – the Art Academy of Latvia. In 1978, alongside Artūrs Riņķis and Andulis Krūmiņš, he organized the landmark exhibition of kinetic art Form. Colour. Dynamics at St Peter’s Church in Riga. In 2013, art historian and curator Irēna Bužinska put together the artist’s first solo exhibition dedicated to his seventeenth anniversary Touch. Unique design, Kinetic objects, Photo-montage, Posters at the Museum of Decorative Arts and Design. She comments: ‘In his kinetic works, Valdis Celms displays an interest in a separate, particular element and his ability to see in it the information and code that gives us the key to the Universe – the greater reality surrounding us.’ Valdis represents earlier generations and when invited to choose between a meeting in an empty office or a Zoom call, he prefers the former option – meeting in person. During the past year, it is almost the only interview I have had in this format. We set off in 1970, moving towards 2021, and this point of departure is not coincidental for either of us.

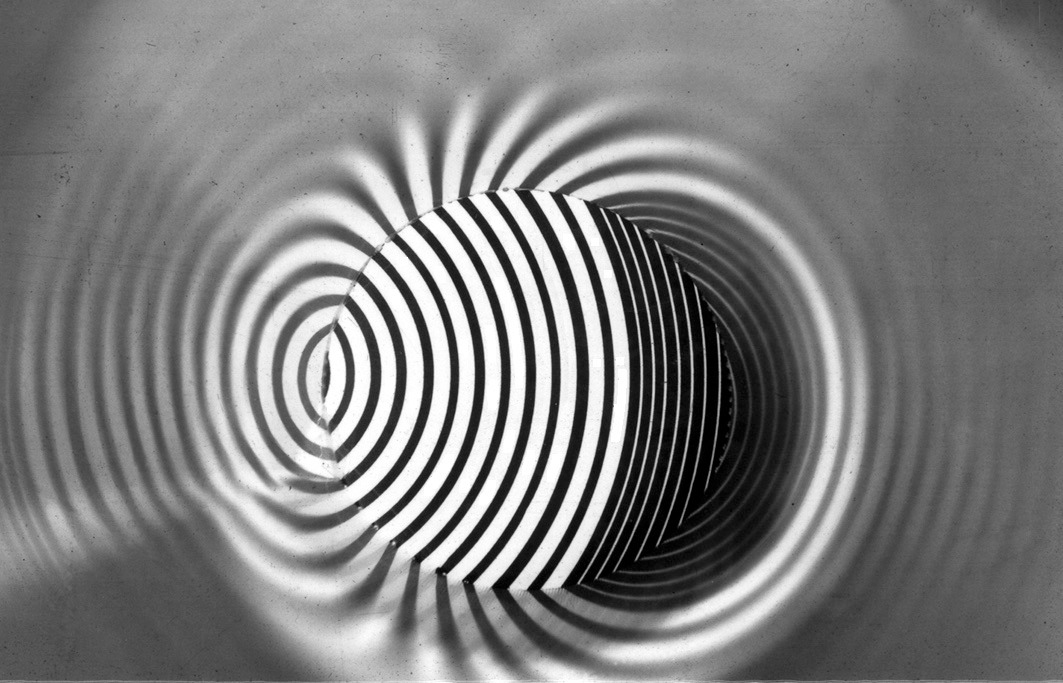

Eyesight cabinet. Beyond-World Space. 1970. Photography – motion study of a kinetic object / 18 x 24 cm,1970

Yesterday, reading your biography, I caught myself thinking… You graduated from the Art Academy in 1970, and I was born that year. So, I am very curious – what was this time like? What feelings do you have for this period?

At the time, a degree from the Art Academy was perceived with great respect. ‘An artist!’ people would say. It was almost the same with actors and writers. Moreover, the professional environment at the Academy was very different from the atmosphere in the society at large. There was way more freedom of speech in a professional sense. However, two currents collided – the academic with the ideological framework, traditionalism with the age of new ideas and the need to get with the times for the sake of progress. It became especially obvious when the Academy created new departments – industrial arts, interior and design. When I was studying at the Academy, the Industrial Arts Department, later the Department of Design, was about to be established and the study programme was still being created. The professional and ethical code was established, and professional standards were outlined.

These disciplines – industrial arts, design, interior design – were officially categorized as practical arts. Whereas, fine arts, graphic design and sculpture were rather ideological. Our department also had professors unconventional for the Academy who introduced us to the history of technological culture and industrialism. Many young talents were applying because of the creative freedom and room for experimentation it provided. During the end of year exhibitions, everyone – painters, graphic artists – would rush to the stands of designers anticipating some out-there pieces. It was a source of new ideas, new forms that pushed the boundaries of the more traditional artforms inviting them to break out of stagnation. However, it was a gradual process that took several more years.

The students were allowed to put up solo shows at the Academy. On the one hand, it was done to have oversight – to make sure these innovators were steering clear of ideologically inappropriate ideas. On the other hand, they taught independence and raised the overall visual quality – for the ones ‘overseeing’ also. There was mutual evolution.

In 1972, the Artists’ Union put on a big show called Svētki (Celebration) at the Riga Bourse building in the Dome square. That’s where the first generation of graduate designers and interior artists announced themselves. True modern art was on display – kinetic art, op art, environmental sculptures. Such were the beginnings of many things that we see continue today, things that have evolved and gotten a new lease of life.

Just like the Song Festival which was historically dedicated to all kinds of anniversaries celebrating the Russian Empire, the Academy also had its ‘ideological commitments’. But the very theme of celebration offered great freedom of interpretation – it could be a national ‘hammer and sickle’ holiday, or a people’s festival, a carnival, or a celebration of spirit. It was an attempt to escape the situation in which everything is forbidden. In fact, you can always find things that are permitted. It is a matter of intent… and skill. ‘Nothing’s allowed, everything’s prohibited,’ was too often used to excuse one’s own inaction.

Design, poster and textile art exhibitions were frequently held and were evolving quite actively. It was a wonderful time in my life, although it was, of course, very very different from the atmosphere in society in general.

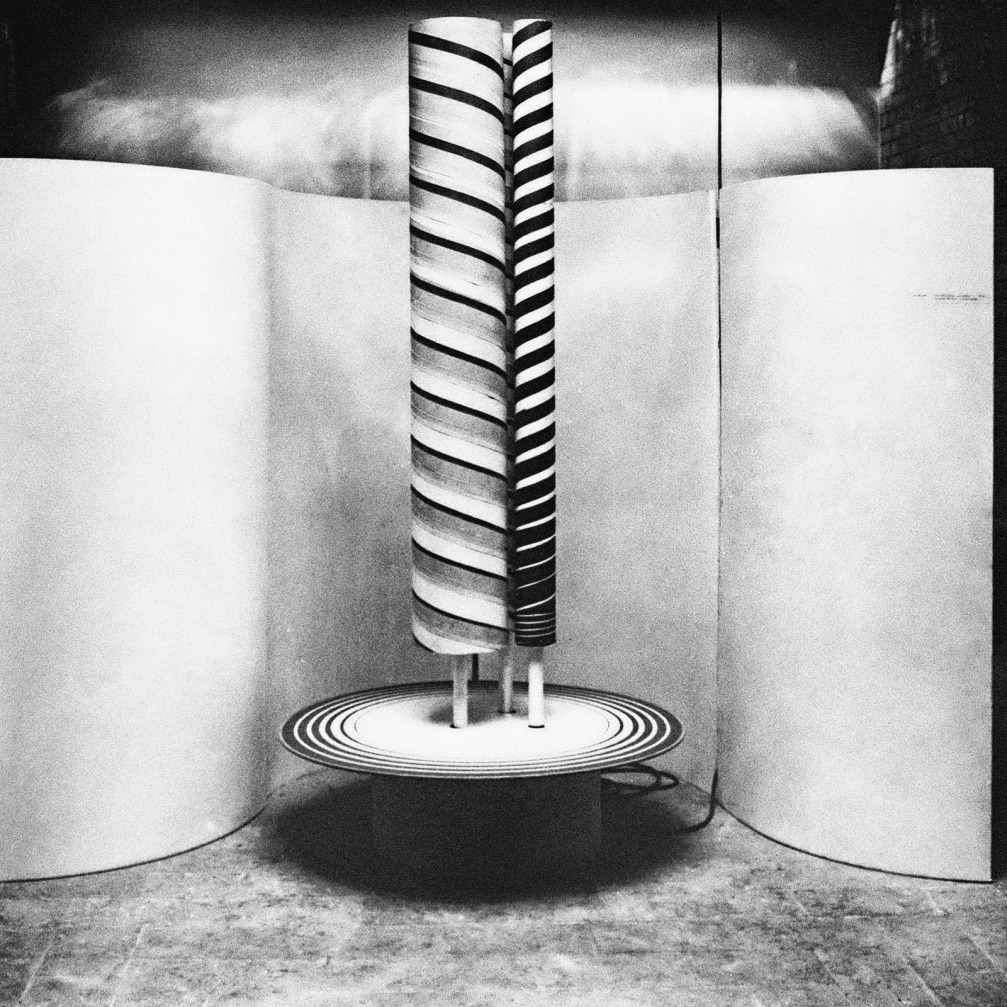

Valdis Celms. Rotating Cylinders, exhibition ‘Form. Colour. Dynamics.' at St Peter’s Church in Riga, 1978

What works did you exhibit at the 1972 exhibition Celebration?

Still being a student, I started a job with a household chemicals manufacturer in Pārdaugava as part of their team of designers. So I was standing firmly on my own two feet. I had two works at the show. The op art cube and the rotating cylinders – kinetics, also an op art piece. I also participated in designing the ‘centrepiece’ of the exhibition which was a collective project made by approximately 40–45 authors. It was a large room where the architect and interior artist Jānis Pipurs offered for ‘interpretation’ spatial structures – 2.5x2.5 meter cubes. In these cubes, various objects were placed and exhibited. Contemporary geometry entered the classical Venetian style building with columns and marble floors. And each cube was a separate event or a separate setting – some of them created by entire teams of artists. There were many different things there, even a soft floor that started ‘squeaking’ when you stepped on it. Or a giant, two-meter tall geometric flower, a swimming fish oddly twitching, etc.

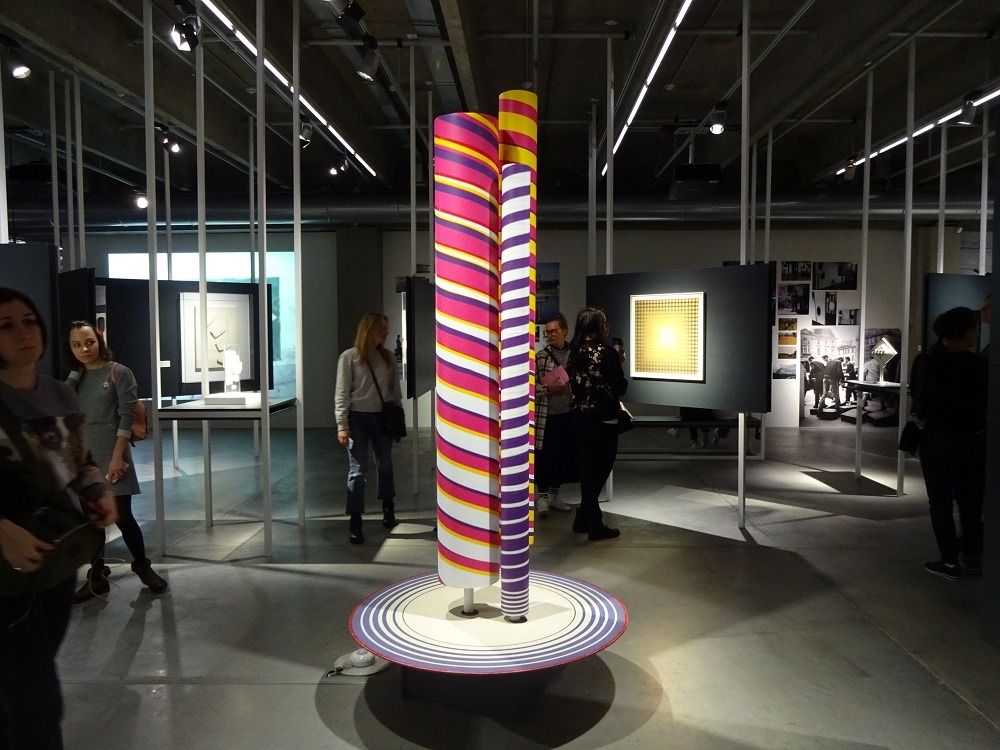

At the time I enjoyed observing how form is born, or how one form flows into another – you can track the process but the exact moment of transformation is impossible to capture. Something simultaneously is and isn’t. I was interested in this borderline state: doubt and certainty at once… Various publications about the exhibition appeared in the press, and sometimes the image of my rotating cylinders was the only illustration. I chose to base the work on the spiral – one of the key elements of sacred geometry. And at the time it was important to me to show movement upwards and downwards at the same time. In Soviet times, they used to say that everything is growing as a spiral towards a higher stage of development. Such was the scientifically supported predestination, and nothing could be done about this law of nature and history. This is not what I believed, since the spiral by definition includes movement in either direction. Outwards, back to the centre; upwards and downwards. It is an ambivalent thing – depending on how you look at it…

For example, the moon in the sky descends as it approaches a new ascent. There is inhale and then there is exhale. Growth can not be a movement in one single direction, development in itself is cyclical. And it doesn’t always result in us reaching a higher stage. That is what I wanted to show. Moreover, it was a site-specific object that was shaping the environment around itself. For exhibitions, it would always be placed at the centre of the room or by the entrance. Recently at the Garage museum in Moscow, it was also marking a sort of centre… This effect is ensured by both the form of the object and by the manner in which it works.

Valda Celma. Rotating Cylinders – Transatlantic Alternative. 2018. Contemporary Art Centre Garage, Moscow, Russia

How did your ideas come about back then? Were they the result of observation or your research into certain ideas, for instance, sacred geometry which you mentioned? Before the Academy, you did receive a rather practical education at the Technical School for Construction …

You’ve captured it perfectly. After tech school, I also worked at a constructors’ office, and I was always drawn to structural buildings, structured forms. And structural geometry… which is as close as it gets to sacred geometry. I wanted to explore how these structures are reflected or interpreted in different cultures. The same signs can acquire different symbolic contents in different cultures. In the early ’70s, when asked what my creed was, I gave the same answer I would now: I am interested in the structure of poetry and the poetry of structure. Mind and feelings have to melt into one to create harmony. No extremes, no tilt towards either side can provide true fulfilment. Nor rye bread nor cake alone is enough to sustain us. Although, from time to time, a bit of cake is exactly what you need. And it is art’s job to teach us a sense of proportion in these matters.

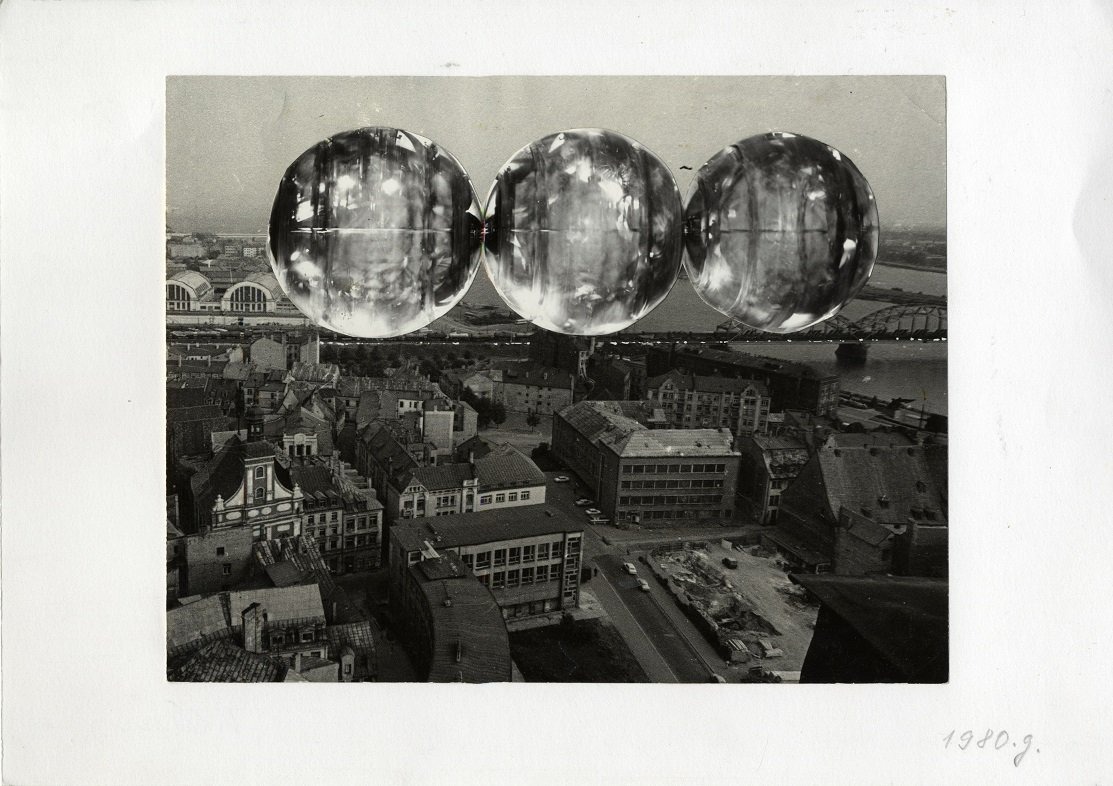

Offsets in Time (Shredded space), photocollage, 15,5 x 23,5 cm, 1980

My fascination with structures was stimulated also by my interest in structural architecture. It is not merely constructivism, it is a structural approach in general – the ability to work with large-scale systems. And, when I encountered tradition in various cultures, including Latvian, I saw patterns everywhere present a universal rhythm that in a spatial sense we call structure in the modern world. And I was deeply intrigued by this, especially during my study years at the Academy. Of course, my curiosity reached beyond the official study programme which did not have things like the VHUTEMAS (Higher Art and Technical Studios, Russian State school founded in 1920 – Ed.) approach, courses dealing with Latvian patterns or French surrealist poetry. And I was interested in all of it.

You know, the lines by Paul Eluard:

‘The flow of the river

The expanse of the sky

The wind, the leaf and the wing

The looking and the saying

And my loving

Everything is motion.’

I found my feeling here – the embodiment of my worldview where the rational and irrational interlace. In these structures, therefore, I am not simply after an esthetic. I am after imagery that could connect us to the entirety of the former cultural tradition.

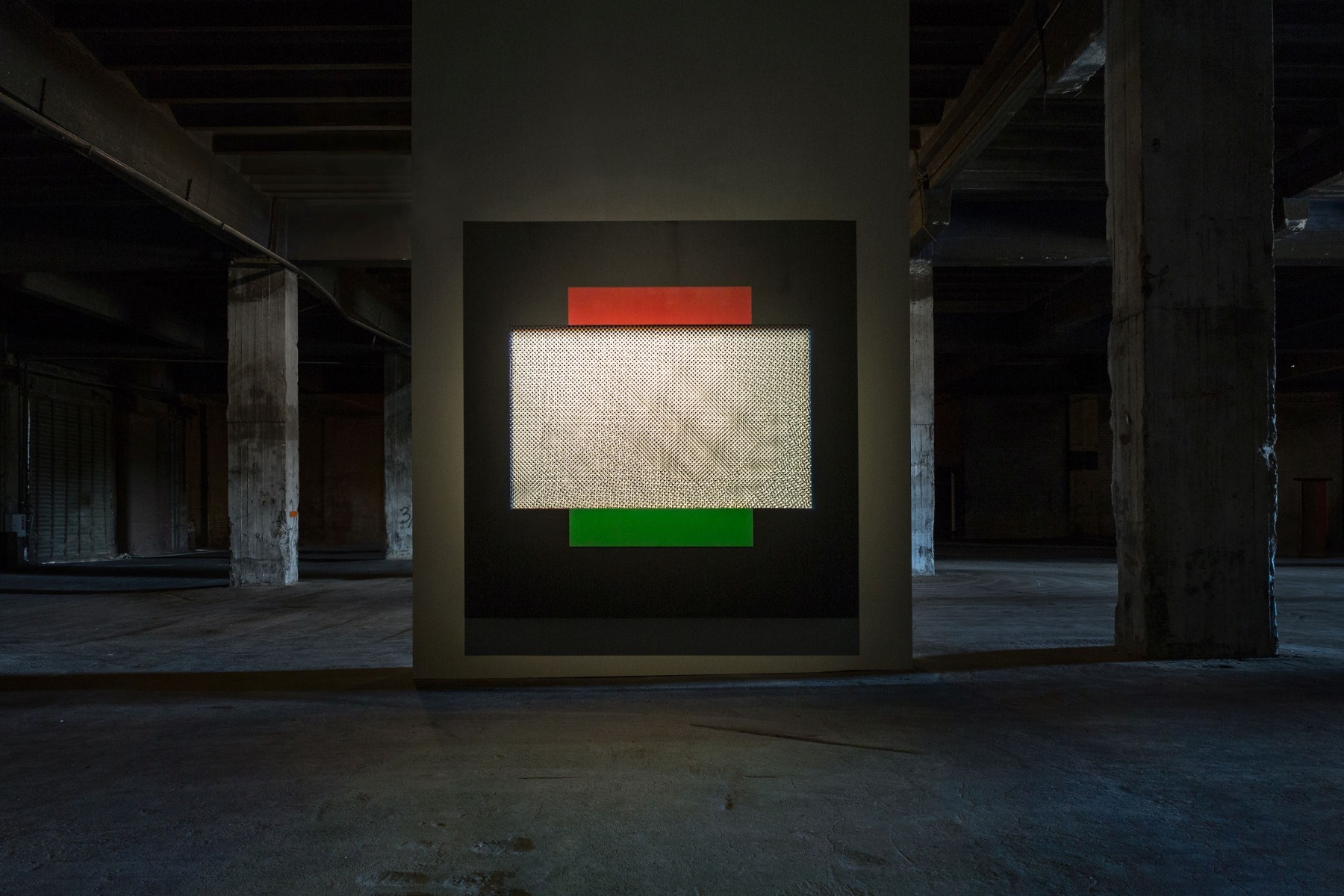

Valdis Celms, Rhythms of Life, 1969/1970 - 2020. Kinetic object, plywood, acrylic glass, vinyl cut, motor, paint, 3 × 3 × circa 0.5 metres / at the 2nd Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art ‘and suddenly it all blossoms’ / Courtesy of the artist / Commissioned by the 2nd Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art / Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

But did you employ certain existing archetypal structures or rather try to invent something completely new?

Good question. In my opinion, kinetics is a paradoxical occurrence – as art, it emerged due to technological advancements of the 20th century, however, the structures themselves as curious phenomena have existed forever since movement already is part of nature, is of nature. Observing movement was something that has always been interesting to poets. In the traditional culture, and Latvian traditional culture as well, the world is perceived as motion. It isn’t static. Every symbol is the sum of movements. And this way we continue down the archetypal path.

Meaning, I use both the avant-garde approach and my entirely archetypal cultural background. For instance, the most recent work that I created was Rhythms of Life, exhibited at the Riga Biennial. What is it? It is a large screen, a red strip and a green strip. Let’s start with the fact that all screens utilize the methods of seduction known to us since the times of ancient magic. A screen is like a mandala, a framed space commanding the attention of the spectator. You are watching, unable to look away. Because the frame separates you from the rest of the world. What else… What else did I use in this piece? Light, movement, sound. All that is missing is scent.

In nature, the sky’s the screen, in the cultural tradition – a white page we create or express our worldviews on. However, it seems we have ended up in the age of screens, the age of misinformation and manipulation. We are not perceiving the world like we used to; we don’t look at the stars. Instead, we look at the ‘stars’ on our screens, we see what the directors of the political show allow us to see.

‘The stars of the silver screen’ – this phrase is not accidental…

In the 1970s you were also working with a team of designers as you mentioned. Was this a way of combining your practical and artistic side?

Yes, I was doing that until 1976 when I actively started working on Positron and realized I won’t be able to do it all – the workload was too great. I joined the staff of the Riga Factory of Decorative Arts and focused only on that.

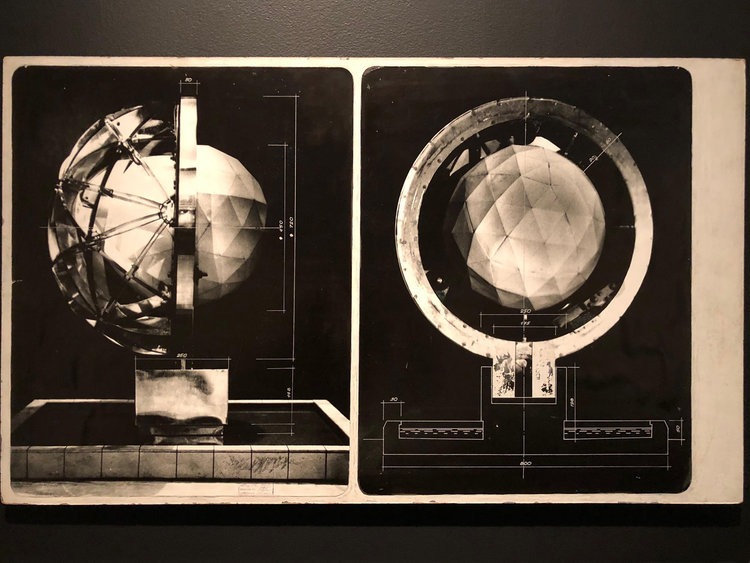

Kinetic object POSITRON. 1976. Design of the model for kinetic object

Positron was your first commissioned piece?

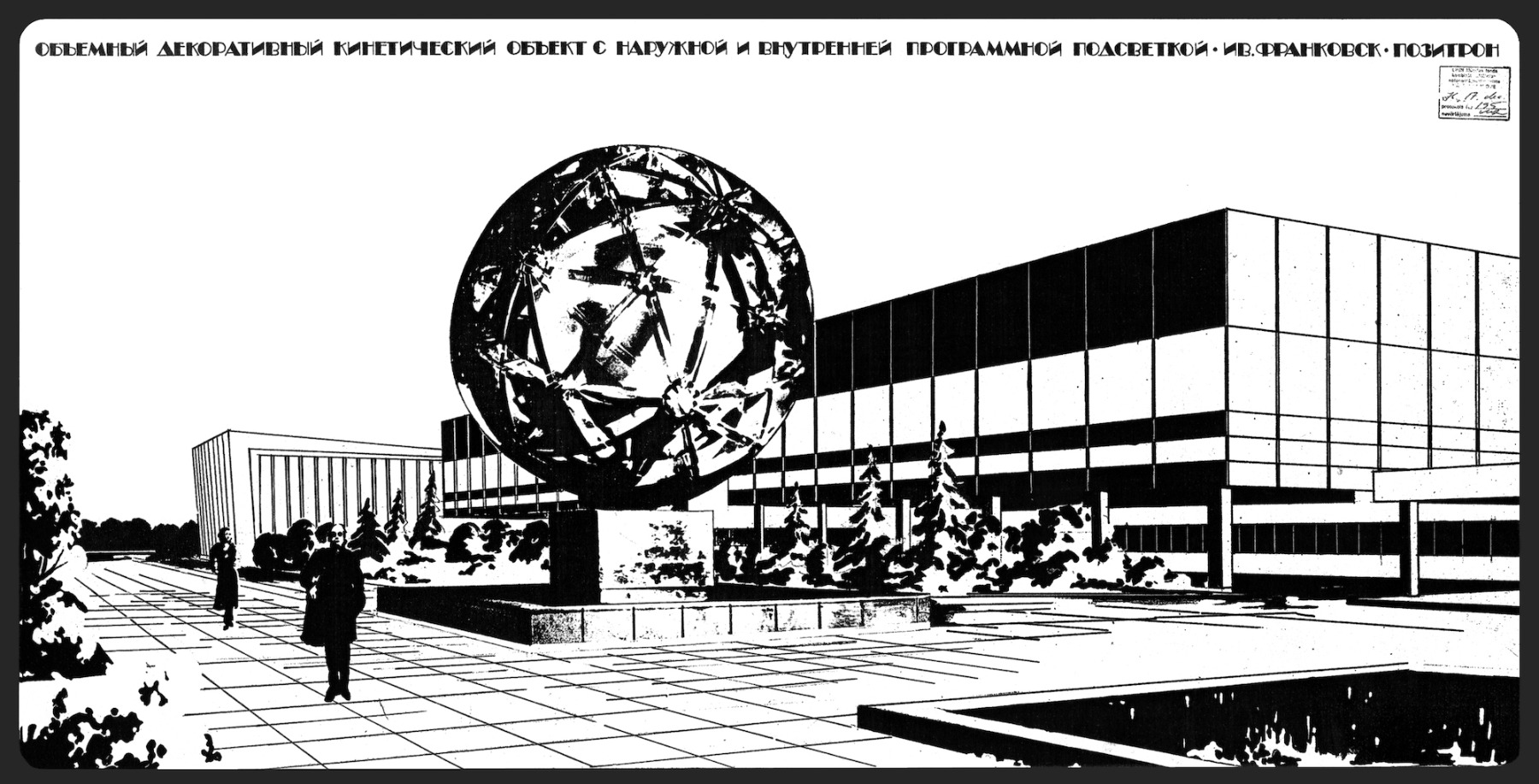

Apart from the design of the Radio telescope antenna five years prior, yes, it was my first. Prior to that, I was creating kinetic objects on my own initiative and at my own expense. And suddenly I got this commission from a large manufacturer of electronics from Ivano-Frankivsk, also called Positron. People from our factory had already been making something for them and earned us a good reputation. And the architecture they had there was typical Soviet modernism – massive ‘boxes’ stretching for hundreds of meters. But there was also a vast recreational and park area where they wanted to place a sculpture – at the entrance of the corporate building. As an accent to organize the space. I was free to do whatever I wanted. There were no restrictions, they said: ‘Anything you come up with, we’ll consider’. At first, I had the idea to build something upwards or use a pinecone shape, and all kinds of other ideas. But having sufficiently analysed the circumstances, taking into account the location, the profile of the factory which was electronics, I finalised my idea. The very notion of ‘positron’ was leading me to create something connected to science and technology, but I did not want to simply illustrate the notion. I wished to create something more crystalline with a kernel, and for it to glow. For all intents and purposes, my subject was connected to matter and energy. And we associate matter with something more or less dense, while energy is something intangible, let’s say, light. I concluded that it needs to have a geometrised kernel encased by shiny plates of mirrors as an ornamental shell. Initially, the idea was to make the core static, but then I imagined what would happen to the object during the winter and realized: it will get covered by snow and, because of ice, everything will start cracking and there will be no way to properly remove the snow and ice. The object not only had to be mounted but also maintained for a long time… Besides, the size of it was rather impressive – 7 meters high, plus 2 meters for the base. Who can climb that high! That’s when I knew I had to make a construction that rotates. And for this kernel not merely to be revolving, but spinning – rolling in place. This not only made the movement more diverse, but also made maintenance easier – the surface that was just on top briskly ‘spins’ to the bottom, and so on. This solution also gave more freedom for visual perception because it produced a variety of movements, an entire polyphony of motion. The project was finalized and the art council approved the second or third proposition, a model was built, and it all went off. The factory bosses were highly progressive people, they immediately started looking for lasers to cut metal and stainless steel. But the project was suddenly brought to a halt. Why? Precisely because the director was so progressive. He was promoted and moved to Moscow. And the new director wanted little to do with the project. As he thought of himself, by definition, to be in charge of the place and responsible for new orders and decisions rather than finishing what someone else had started.

Some of the materials for the project remained in my possession and gained a new life. Based on the Positron ideas, I created various photomontage works and variations of the object scaled down for indoors. Later, the initial project was bought by the famous Zimmerli Art Museum in America and earned recognition in its own right.

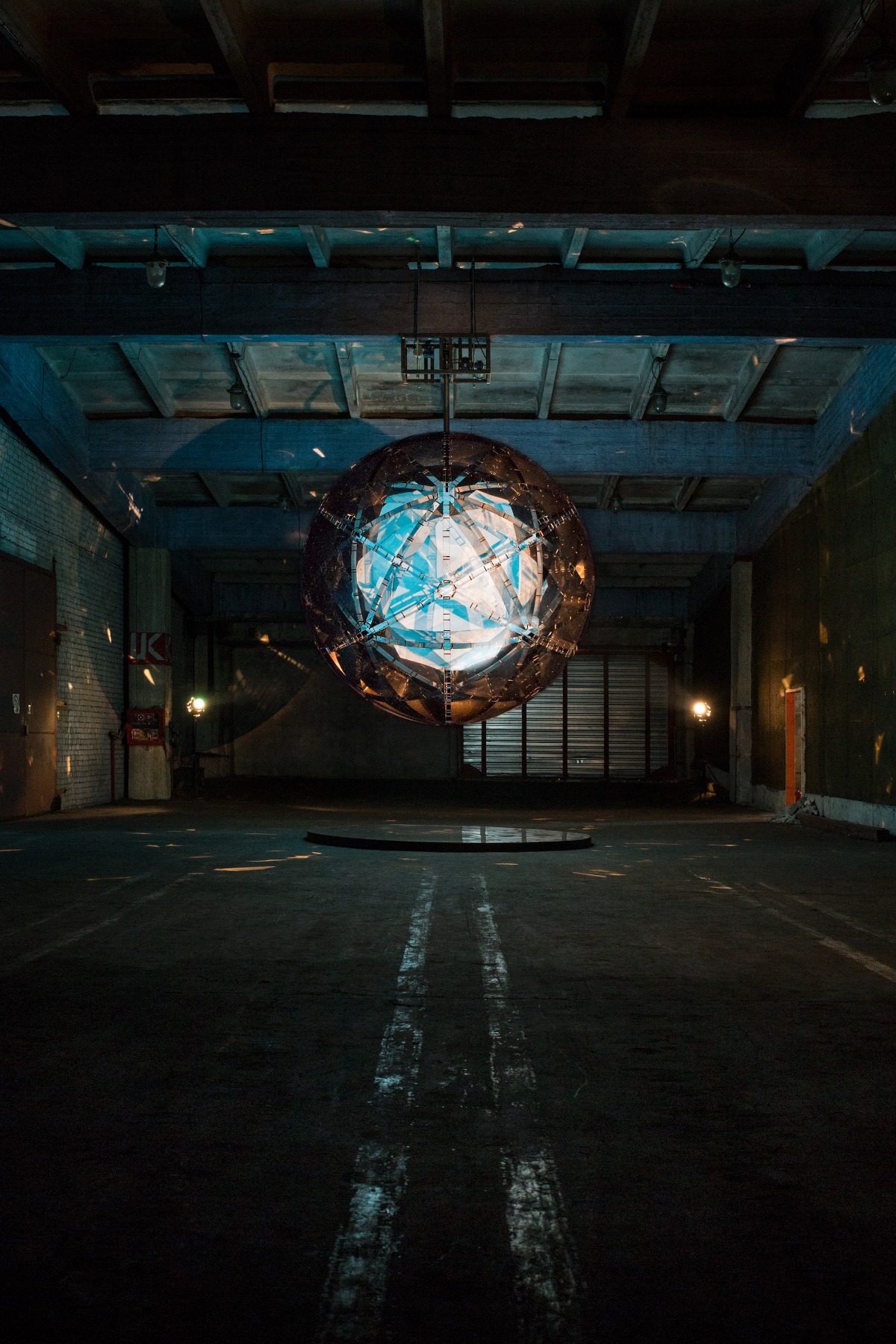

Valda Celma, Positron, 1976-2020. Kinetic sculpture, fiberglass, stainless steel, Motor, D = 3,6 m / at the 2nd Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art ‘and suddenly it all blossoms’ / Courtesy of the artist / Commissioned by the 2nd Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art, 2020. Photo: Hedi Jaansoo

How did it feel to see your idea finally brought to life for the Riga Biennial?

You know, it was a totally mystical and unreal feeling because this project had for so long remained a dream. The art committee of the Biennial had Kaspars Vanags and the head curator Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel who both reacted to the idea quickly and positively. Nonetheless, while we had no information about the location and other details about the display, I was rather on stand-by. But once they showed me the exact spot in Andrejsala, it was immediately clear to me that it can and should be done. Besides, I didn’t have to worry about the maintenance of the object after the Biennial since it had been commissioned by RIBOCA and they took on sole responsibility for the future of Positron.

For the entire year of the Biennial, I was living in this ideal world in which my ideas are understood and recognized as worthy of bringing to life. And they were brought to life according to the highest technological standards. We went through many stages. Oskars Plataiskalns and his Decoration Workshop undertook the preparation, the building and the mounting of the construction. Of course, I owe a great thanks to the producers of the Biennial – Dita Birkenšteina and Kitija Vasiļjeva.

Both pieces exhibited at the Biennial – Rhythms of Life and Positron – were first conceived in the ’70s. Rhythms of Life had also never been realised before. And under these circumstances, it gained a new life and additional meaning.

Valda Celma, Positron, 1976-2020. Kinetic sculpture at the at the 2nd Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art ‘and suddenly it all blossoms’ 2020. Photo: Jeļena Kononova

The Biennial curator Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel has often emphasized the similarities of the atmosphere in Andrejsala with that of the Andrei Tarkovsky films, namely Stalker. And here, this hall in a huge seaport warehouse with your Positron in it, for me, seemed a direct connection to the room that grants wishes. The sphere the protagonists are moving towards through the ‘Zone’. A sense of miracle…

Yes, I agree. It had a tangible unreality there. The location was spot on. And I as an artist was absolutely happy with the result.

Kinetic object POSITRON. 1976. Design of the model for kinetic object, proposal for a factory in Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine

I wonder what Positron would look like had it been made back then – next to that factory in Ivano-Frankivsk…

It is hard to tell. Of course, the location makes a difference – whether it is outdoors or indoors. But it is entirely possible that this was the perfect way for the idea to be brought into this world after all. Maybe it’s not so bad that the ideas of the artists in the Soviet era didn’t all come true. The quality of construction materials was pretty bad back then. The result could have been very disappointing. Or I would have to look at the things not working anymore and falling apart with sadness. Now, these unrealized objects are inhabiting exhibition halls or our imaginations. It was probably meant to be.

What was the overall attitude towards kinetic art in the ’70s? I recall that you and the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art invited Viacheslav Koleichuk, another renowned kineticist from the former Soviet Union, to give a lecture in Riga. He claimed that kinetics at the time was in a sort of an in-between state: not entirely endorsed, neither completely prohibited.

I met Koleichuk when some of my kinetic objects had already been made. And when we met for the first time, we really had a lot to talk about. He was a wonderful artist, able to laugh at himself and very human…

But with regards to the perception in society at large… We were not officially recognized as artists. We were seen as designers. But to designers, we were artists, representatives of kinetic art. And that, too, had different gradations – some were more interested in the technical or even entertainment aspects, some in the spiritual, philosophical concepts of it.

After the joint exhibition Form. Colour. Dynamics with works by me, Artūrs Riņķis and Andulis Krūmiņš in 1978, in one of the meetings, I said directly: this is kinetic art, kinetic advertising, and kinetic design. And they can also exist separately. But the exhibition itself is a step towards process art that we perceive precisely in the process.

At the same time, the Art Academy issued a publication that suggested that the interest shown towards our art was unwarranted, that, although we were ‘decent lads’, we were nothing special and had no deeper connections with tradition. That’s when critic Jānis Borgs put an end to this type of thinking in his article for the Māksla (Art) magazine where he wrote that art and design are not to be juxtaposed because these fields often overlap. And kinetics is both a part of art and design. Later, the term ‘unique design’ was used to refer to us as well, but I was using the term ‘art-design’ that felt more adequate and comprehensive. People were showing interest all the way up till the ’80s, but after the early ’90s, the great period of forgetfulness began and kinetic art was of no interest to critics, nor to the public. But during the last decade, fascination has developed again – rather remarkably.

Valdis Celms, Dreadful transit. 1980. Photo collage, 16 x 20,5 cm

Why do you think that is?

Well, I think that the passing of time provided a sense of perspective and allowed people to see the true value of certain things, and also that what we were doing was literally in step with the global art movements. During the ’60s and ’70s, we were evolving in the same direction although separated by the Iron Curtain.

By the way, that is precisely why the retrospective exhibition of kinetic art at the Garage museum in Moscow was titled The Other Trans-Atlantic. In a way, it truly was an alternate reality. No comments. However, undoubtedly, it was a phenomenon of its time. Vasarely’s art was a frequent subject of conversation. Calder, Schoffer and Tinguely, too. But among kineticists mainly, of course.

It was one of the few intellectual islands that existed in Soviet reality.

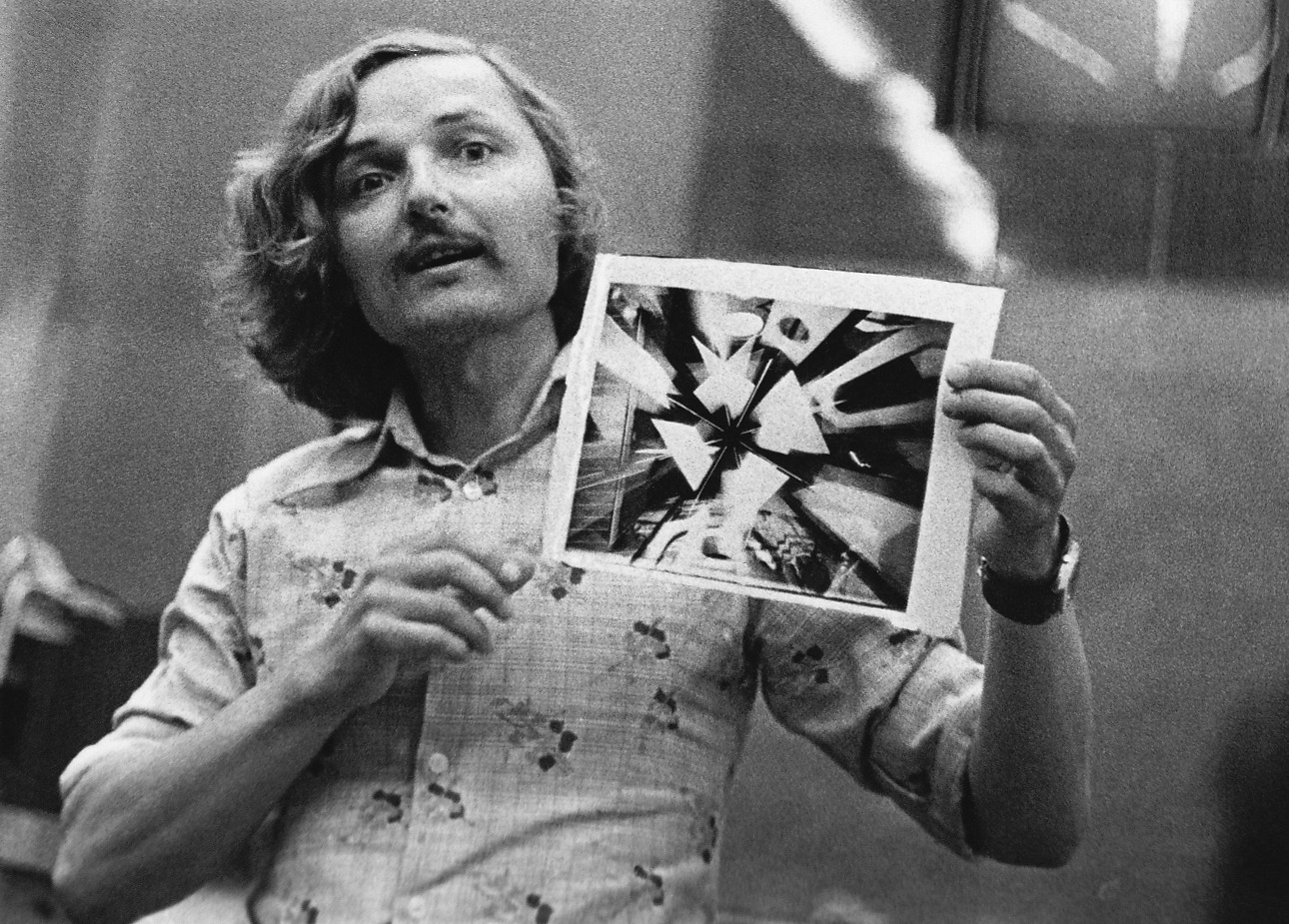

Valdis Celms at the conference 'Light and Music' in Kazan. 1979

I believe that the quality of collective technical thought is essential for this type of art, and in Latvia, it was rather high at the time.

Yes, I agree. It is not only the level on which the creators construct their ideas that is important; it also matters that the public has access to the technological foundations for bringing them forth. And we had just that. We had the Komutators factory, we had the institutes at the Academy of Science where our designer colleagues worked. But, instead of taking place officially, it was all happening on the level of personal contacts and was grounded in a shared desire and care for self-expression. It took different forms, among them amateur cinema. The only video documentation of Form. Colour. Dynamics is a film made by my friend Aivars Budahs who worked at Komutators.

But there were contacts with other ‘intellectual islands’ as well, and not only in Moscow or Leningrad. For instance, people were interested in colour music, and Bulat Galeyev was running his Prometheus Constructor Research Institute in Kazan that was conducting kinetic light and sound experiments. They had seminars and festivals there, and we also got to attend. Later, Galeyev became the resident Soviet Union correspondent for the Leonardo journal of sciences (founded in 1968, Paris, and since the early ’80s published by the MIT Press San Francisco, it focuses on innovative arts that integrate technology – Ed.), and, thanks to his efforts, an entire issue was devoted to the USSR avant-garde – artists working with light, movement, and so on. Various approaches existed in the genre of colour music as well. Some believed that machines and light bulbs blinking in the rhythm of the music were enough. But I, Krūmiņš, and Riņķis were certain that such a path was futile and music and light had to be fused in the platform of creative imagination. There had to be colour and light equivalents to the very spirit of music, not merely its rhythmic structure. Moreover, the artistic idea had to come before technology. Not everything should be simply turned into millions of bulbs.

Valdis Celms, Rhythms of Life, 1969/1970 - 2020. Kinetic object at the 2nd Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art ‘and suddenly it all blossoms’, 2020. Photo: Didzis Grozds

You have vast artistic experience not only with kinetics but also with design, posters, research into Latvian symbols and ornaments, and so on. Let’s return to the start and imagine that you will be graduating from the Art Academy in 2021. What advice would you give yourself as a beginner?

That’s a tricky question… Each era is unique in its own way. At the time, it seemed straightforward that one must do this and no other. But from today’s perspective, I would emphasize several things that, of course, I don’t mean to be categorical. First of all, it’s important to understand that the world does not begin with you. It’s not like everything starts here and now – thanks to your contribution. And it follows that it is truly worth studying the best works of previous generations. It is also not necessary to idealize the freshest ideas and exaggerate their progressiveness. Already in the ’70s, I concluded that the most interesting works are not the ones exhibiting mere dry concepts. One must remain open to other layers and influences. When you look at the best constructivist works, you notice that, in fact, there is so much ‘non-constructivism’ in them. There’s so much irrational there, while a surreal work can have constructivist influences. For instance, I like to think of Māris Ārgalis as a constructive surrealist.

Another thing – one must study nature. Nature is our true judge. And it does not mean ‘painting landscapes’ exclusively. Our culture maintains the understanding that nature is also the Universe. The difference is only in the scale: nature is microlevel, and the Universe is macrolevel.

Many think this way: I have to earn worldwide recognition because I am a world-class artist, after all. But I think there is something wrong with the sequence, the order of actions here. If you are unable to feel that you belong to a place, a culture, language and values that you grew up in, I doubt that you can belong to anything global. I would sincerely question that.

So, think, evaluate, seek a balance between yourself and the world, between yourself as a successor of the work started by previous generations and as a spiritual being on the global scale. The local and the global will always coexist. It will never be that an individual is separated from some type of global happiness. That is not how the world works. There are meadows in bloom and each flower is unique to the specific ecosystem, specific niche. Evolution does not mean that in thousands of years flowers will gradually die out and give way to some uniform biomass. Our scattering across the globe can also mean that we become blood cells or elements within some foreign organism.

I believe that if your work is of great local value, it will inevitably be valuable globally and universally. This belief was inspired in me by our symbols, patterns, ornaments which contain these structures of sacred geometry, this global thought. Human values are certainly universal, but they cannot cancel national culture. Your core is tied to your place, and if you don’t have a place, you have nowhere to grow roots – you cannot grow. And what art can we be talking about then? That is how I see it.

Valdis Celms during his studies at the Art Academy of Latvia, 1969

Nowadays, the widespread opinion is that you should definitely go and live or study abroad, and then return to your own land. Just recently Maija Kurševa was talking about this in an interview…

That is different. To study and return! Latvians have the tale about Sprīdītis and his search for the happy place. But the hero’s achievement is not him taking his hat and leaving home. No, it is his ability to return – to come home.