Against good taste

An interview with a finalist for the the 2021 Purvītis Prize, artist Kaspars Groševs

A brazen wind drives the dust along the sidewalks, empty due to it being Saturday as well as the middle of a pandemic, as I head to 427, an art gallery near Avotu iela. The euphoric radiance of the spring afternoon sun, together with the mood of an impending sunset – a motif worthy of Impressionist paintings – gives a bohemian hue to this area now popular with the alternative culture crowd. The gallery is located at Stabu iela 70, on the corner of Avotu iela, the latter street being the chief identifier of its location to most Rigans, since it is this hundred-year-old, intricate and architecturally heterogeneous thoroughfare that dominates the neighbourhood. Unlike the more central arteries of the capital, it has the (generally) leisurely and cosy character of worn and eccentric side streets usually found on the outskirts of town. In all, suitable environs for the gallery of Kaspars Groševs, a finalist for the the 2021 Purvītis Prize, Latvia’s highest art award. The gallery is one of several counter-cultural institutions that have been attracted to this corner of the city as yet unexplored by the middle-class – for just as elsewhere in the world, gentrification is taking place in Riga. On the day that my interview with the Purvītis Prize nominee transpires in the gallery currently darkened by plywood-covered windows, the space is clearly in transition – the previous exhibition (Jānis Dzirnieks' Flīzēta upe / Tiled River) has just been taken down and the next one is going up – Darja Meļņikova's show, set to open on 27 April. The emptiness of the gallery contrasts with the material and emotional density of Different Room, the work created by the gallery’s owner for the exhibition Sound We See. Space We Hear at the 2020 Cēsis Art Festival and which secured Groševs a spot on the short list for the Purvītis Prize.

When I met you, I didn't realise you were an artist – I perceived you as a musician. Which came first for you, music or art? And why did you choose to study art over music?

Looking back to my childhood and my early teens, art probably came in first because I liked to draw. But music soon followed, with experiments with cassettes and headphones that I remade into a microphone. I drew comics and messed around – I wasn’t aiming for serious art. Music enticed me with its quick results. I kept notebooks with my comics and used to show them to a couple of friends. It was the same with music – I’d record some cassettes and play them for a couple of friends. This process pulled me in; it seemed more interesting than art. In the last years of primary school in the late 1990s, I started making some electronic music; I played in groups. At first I made breakbeat and drum’n’base pieces, then I started playing nu metal, then I joined some hardcore bands, but at the same time, I kept on making electronic music as well. I was going to the Janis Rozentāls Art High School, and since I had never had the desire to properly learn music or music theory, I relied only on my intuition when it came to music. Art was on a more professional level, and I enrolled at the Art Academy. But music followed along in parallel, and over the years I began to think about what unites my artistic practice with my work as a musician. I began looking for connections, and I focused on experiments and the procedural nature of music. And things have stayed that way. If in the past I separated the musician from the artist in me, then now I’m more apt to approach music from the position of an artist.

Music and art are increasingly blending together for me.

What does that mean – to approach music from the position of an artist?

It refers to the methods and concepts that I follow when making sound. Music and art are increasingly blending together for me. If you look at the history of modern music and recorded sound after the advent of synthesizers, it’s been more about form, whereas since the 60s, conceptual art has changed the way that people think about and create visual art. At the beginning of my career as an artist, I too was interested in abstract ideas about art – for instance, Sol LeWitt's statements about art, which were like a "bible" of art for me for a while there. But with the music, there was a conflicting feeling; for example, while at I was at the Art Academy, I liked Terre Temlitz and his very conceptual approach, and Carl Michael von Hausswolff – those kinds of musicians. But I myself never reached such a point of "radicalism" because I had the conflicting feeling that I also like the form and texture of the music – its creation. Everything that, according to Marcel Duchamp, would be retinal in the visual arts. Namely, painting, which in his opinion is only a retinal experience and, accordingly, not interesting. I really like the "substance" of music, and I have always liked to experiment with different instruments – cassette players, reel-to-reel tape recorders, old organs. Only now have I become, so to speak, more modern, making music with various synthesizers and a computer... Art, on the other hand, I have always approached with conceptual, Fluxus-style ideas, with hidden or subjective jokes. But in art high school, in some masochistic sense, I also really liked painting – a class that many students did not like. I loved creating shapes and textures with oil paints. At one point I also liked to create different technique experiments on paper – gluing, spraying, burning, painting, and drawing with different kinds of markers, pens, etc. This also logically connected with my musical activity – namely, my approach to both music and art has a certain procedural nature to it. In music, it’s improvisation. As soon as the instruments are plugged in, the signal sounds and it is sometimes unclear where the tuning ends and the playing starts. It’s similar in art – it is not always clear where the "tuning" ends, at what point a "piece" has been created, and at what point is it already just an encore.

So you’re interested in both the formal and the conceptual in music and art?

One of my former students came up to me after a concert and said – I understand how you make your music. You just press some keys, everything goes into delay [an effect in which a melody is recorded and played back slightly delayed – Ed.], you do whatever comes to mind, and it will always sound very similar. And so it is. This is what I sometimes do in music – I just put the delay to the maximum and achieve the longest time-shift so that it becomes a loop. I use delay as an organic looping machine. My current pedal is basically able to repeat a sound indefinitely. Building sound with delay has long been an essential tool for me. In recent years I’ve started experimenting with other things as well, but in general, in music I always return to conceptual elements. After a break of almost 20 years – when I was a teenager – I’ve started working with samples again.

Did you realise early on that you wanted to connect your life with art?

I attended a regular high school in Imanta [a district of Riga – Ed.] for two years. After 9th or 10th grade, I tried to enroll at the Riga Art and Design Secondary School, but I didn’t know how to do anything, and accordingly, I wasn’t accepted. Then I studied a bit and enrolled at the Janis Rozentāls Art High School. In my first year there I turned 18, I think – I was two years older than everyone else. I went to school there from 18 to 22 years of age, and throughout the same time I played in a hardcore band and went on concert tours. At that time, art was more of a professional thing – to learn Photoshop, how to make videos, etc.

Is anyone in your family involved in art?

My mom studied textile design at the Riga Art and Design Secondary School, but she did not continue down that path. But she has always been very creative and still does embroidery and things like that. My uncle is a photographer and my aunt is an art teacher. My family saw that I liked to draw and encouraged me to do more of it.

Parents are not always supportive of their children's creative ambitions, and often times consider it an impractical choice.

My father was also not very supportive (laughs). I vividly remember once making drum’n’base in my room on some old computer. My father hadn't gone to work because of a migraine, and at one point he burst into my room and said – What is this pointless shit? What will you even be able to do with it in the future?! My father is a builder, but he works solo, never in groups, and sets his own rhythm; I’ve probably inherited that from him. Sometimes he would work, work, work, then he either get a migraine or just got sick of it, and he’d just decide to chill at home in bed for two days and watch TV. I thought it was cool if you could have a job where you could set your own schedule.

I vividly remember once making drum’n’base in my room on some old computer. My father hadn't gone to work because of a migraine, and at one point he burst into my room and said – What is this pointless shit? What will you even be able to do with it in the future?!

Did the fact that your father didn’t really understand your creative expressions give you any psychological complexes?

I’m sure there are some complexes. I understand why people may think that contemporary art is nothing serious. I understand their position. At the same time, I don’t want to do anything differently.

I understand why people may think that contemporary art is nothing serious. I understand their position. At the same time, I don’t want to do anything differently.

I remember an interview in which you said that you are lazy. This could probably be said by many. But perhaps it is as you just said – watching your father, you liked the idea that a person can arrange their schedule as they wish, just like he did. And now you too are free in that sense – you do things the way you want to.

Yes, I sometimes work continuously for several months in a row – I may take one free day a week – but then there are periods when I work less. I’m finally trying to introduce a rhythm into my days, because for a long time it was like throwing water on whatever was burning at that moment.

You said you went to a regular high school for a couple of years. This means that there was a time when you probably felt no real conviction about art as a career choice. Were there other options that you considered?

My father said I had to go to Riga State Gymnasium No. 1 [the top high school in Latvia, with a focus on maths – Ed.]. I went to their preparatory course and realised that it didn't interest me at all, and that I didn't understand a thing. When the day of the entrance exam came, I told my dad that I was heading out to take the exam, but in fact I just went for a walk around the Old Town and the parks. After a couple of weeks I told my parents that I had tried but, unfortunately, I wasn't accepted (laughs).

Do they now know the truth of the matter?

No, but they won't read this interview anyway. My father certainly won’t.

Has your father come to accept what you do?

Yes, he has come to terms with the fact that I am a… lover of life and a bohemian (smiles).

Art is often a very practical and tangible thing where, as in construction, skills are needed.

Yes; for example, in this gallery repairs are done every two months, and I’m the one who sands and spackles the walls, paints, does everything that needs to be done (laughs).

That’s why it’s surprising that sometimes people view artists as airheads. The artists I know are all very practical people.

(Laughs.) I'm definitely one of the less practical, but there are things I can do. At the back of the gallery, my friend and I – he more than I – have also made a music studio.

Did you also work on the comic magazine KUŠ!?

When I started studying at the Art Academy, I met more experienced people who were senior students and had done more than I had – Maija Kurševa, Anete Melece… It was through them that I came into contact with KUŠ!. At that time I didn't yet know or understand what I wanted to do in art. I had liked comics in my childhood, and thought I might like them now as well. After a couple of years, I realised that I definitely don't like comics.

At some point it became clear that I was moving towards a conceptual practice and the methods used by the 1960s conceptualists – the same Sol LeWitt. He doesn't say anything super new, but what he does say are remarks about what conceptual art is. *Last year we exhibited a work by Sol LeWitt in the gallery. In true conceptual spirit, he never actually executed his works himself. We received from his daughter the permission and instructions to make and exhibit the work. The work was one wall of the gallery divided into three parts: blue, yellow and red, and the whole thing is covered with light pencil tracings. This was done by Amanda Ziemele and Elīna Vītola, who have also been nominated for the Purvītis Prize. Just yesterday we received a letter from the organisation overseeing LeWitt's estate, asking us to send them pictures from the exhibition because we’re going down in history as one of the places where Sol LeWitt's works have been exhibited.

This approach, setting a framework but leaving the means of expression in the hands of the performer, also links back to music, i.e. the Alvin Lucier recordings released by Black Truffle, the music label headed by one of your favorite guitarists, Oren Ambarchi.

I haven't heard that; I don't follow along with the music that is being released at the moment. At all.

Is this a stage for you? Because you usually do follow along with what’s going on in music, right?

What interests me right now in music is finding YouTube videos that have just a few thousand views – marginal and rare recordings.

What are you looking for in YouTube videos with just a few thousand views?

I like experiments beginning from the late 70s and early 80s – the post-punk energy; for a while I was also very interested in “no wave”. I like directness. The experiments of that time were done with seemingly simple instruments, but a lot was done at that time that may not even be possible to do now. A convergence between acoustic instruments and electronics, various mixing techniques, collages, analogue effects. Moreover, many people are now rehashing the 90s, and they’re digging into their old playlists. This also interests me – both 90's electronica and nu metal. In fact, I first heard nu metal at a Fact concert in 1998, if I remember correctly.

Did you play in any of the groups of that time?

For a short time I played in a group with an acquaintance who is now a soloist at the National Opera, as well as with this guy Kaspars Zlidnis, who is currently a cross-fit coach and heads the fairly well-known pop group Gain Fast. Then, of course, I played with Jānis and Dāvis [Burmeisters] from the group Tesa – I played with them in the group In.stora for the longest of any group. A buddy of mine still teases me a bit about that sometimes (smiles). Admittedly, it was a pretty raucous project, but that's exactly what interests me in art right now – that teenage naivete and “superdrive”. When you think that everyone has been doing it wrong, and now we’re going to correct it. During my hardcore period, my friends and acquaintances published anarchist zines done in a DIY aesthetic and printed out with a regular copy machine – and we all read them diligently. At that moment it was such complete pleasure to read those texts, even though your critical mind was fully aware that what was being described was not really possible. Pretty quickly that emotional high dropped to disappointment, however, because you realise: fuck this shit – only the kids of wealthy parents can afford to be anarchists and punks. My realisation after this period was that my parents were not wealthy enough for me to fully enjoy all that “hardcore”. At the Art Academy, I began to think more about practical things – how to make a living and such. Then art became more like a profession, and I did many different things. KUŠ! was one of the first things I became involved with.

Pretty quickly that emotional high dropped to disappointment, however, because you realise: fuck this shit – only the kids of wealthy parents can afford to be anarchists and punks.

But there still is a lot of drawing in your works.

Yes, but I don't really like creating stories. I have a couple of friends who are very good at that – on a new and modern-day level.

What do you mean by that?

There’s this Finnish artist, Jako Pallasvuo, known on Instagram as Avocado Ibuprofen, and his comics are very self-ironic. First of all, he is aware of the positions from which he is talking about – an artist with depression, he’s nearing 40… He observes tiny things – for instance, birds pecking at crumbs at the table next to his – and this leads him to think about completely different things. His field of reference is very broad – obscure artistic mentions, philosophical themes, and, of course, humour. He is an artist who also paints, but he has really flourished in the comics genre. I realised very quickly that I’m no good at coming up with stories, and I’m also not that interested in it. My texts are also more often about language and they feature references, word play, and a certain automatism. Basically, they’re not all that much about telling a logical story, although I do try to put a driving force into them. My texts are more about textures, weird words, language rhythms and such things.

My texts are more about textures, weird words, language rhythms and such things.

From the sidelines, it looks like you're a conceptual artist, but with a grounded grasp of things.

I like simple things you can do yourself. I've never been interested in planning something complicated and then getting someone else to do it. For instance, creating a laser projection or a glass object that I can’t make with my own hands and I’d need a real expert to execute it.

At least on a superficial level, your work does not seem overly ambitious.

I like the Fluxus room at the Vilnius Contemporary Art Centre. There they have a variety of little things and small publications, including audio cassettes. I also like to make audio cassettes – it’s pointless if you make about 20 cassettes. Then 20 people have a cassette, and others don't know anything about it. We never advertise anything; there’s no time for it – also laziness – and there doesn't seem to be any point in it.

What you just said reminds me a bit of Aija Bley's film We Wanted to Change the World. The spirit of art in you seems to be in a purely youthful form. Most artists have gotten into art through the drive of youth, but later on many have, so to speak, become more serious. But the fact that you're passionate about marginal music genres and into YouTube is a sign of the presence of youth. It was through you that I found out about the band 1/2H 1/2W, an unusual group even by alternative music standards.

At Radio Naba [the freeform University of Latvia radio station – Ed.] I had the programme Nākotnes vīzijas (Visions of the Future), which I had been making from the station’s very start. In 2005/2006 I began experimenting with the radio format, and then I invited some musicians to come and play live a couple of times. One of those times was when 1/2H 1/2W came and played; they weren’t even called that at the time – back then they were known as The Best of Early Nineties.

That was the era of MySpace – I first came across them on MySpace, and for a while I didn't believe that they were a Latvian band because they sounded very different and, moreover, it wasn’t possible to contact them for quite a long time.

Of course, MySpace… (smiles). [Mārtiņš] Roķis and I made a show together at Naba and also did stuff on MySpace. At first we played acid jazz, music reminiscent of that being released by the Smalltown Supersound label at the turn of the millennium. After that we went on to material that was more noise-like and experimental. Those few of us who were interested in electronic music, including 1/2H 1/2W, found each other somehow.

When I came upon you, Mārtiņš Roķis, and 1/2H 1/2W, it was a revelation – I thought it was the best new music in Latvia. Not just in terms of sound, but the whole attitude... There was nothing didactic in your music, none of that mission quest and pathos that was indoctrinated into many artists in Soviet times. It seemed refreshing.

I’ve never thought that much about it, but if I do, then yes, I probably have always been more drawn towards the prevailing winds of opposition and an alternative view of things. That’s also a holdover from my hardcore days. It was a time when the first Skaņu mežs festivals [an annual experimental music and film festival – Ed.] were taking place, when we’d come together to party and play. I was studying at the academy, and I thought – What is going on here in Latvia? You can count the number of good artists on one hand, and the number of interesting musicians on the other. At that moment, it felt like everything was shit. Now, of course, I have realised that very interesting things were indeed happening in Latvia at the turn of the millennium, but that sense probably came from the fact that we really wanted to indulge in music – each one of us was deeply immersed in it. I haven’t been as involved in making music ever since.

Is that due to the electronic music explosion that happened at the turn of the millennium?

Yes, and also with the possibilities provided by the computers that I had access to as a Visual Communication student at the academy. I also had access to very good condenser microphones, Blue microphones, and film and video equipment. Of course, I used that equipment for my student projects, but often I’d use the condenser microphones to record various sounds and noises at home. The technical possibilities were there, and it was a time when I really wanted to do something – I had what is called “a sense of urgency” in English.

You probably never thought that you would become a gallerist.

No, not at all; but I am not a gallerist. There was never such a plan. It just arose from conversations with friends. We’d talk about the need for such a thing from time to time at parties, and then I thought about it – really, there are no small, independent galleries in Riga that would show something fresher, more experimental, and maybe not as serious and important as the large institutions do. A gallery where we could also be allowed to make some jokes and small “gestures”. This led to the opening of the gallery. Two years before the opening of 427, if someone had said that I would soon be running a gallery, I wouldn't have believed them. It came into being rapidly and spontaneously.

After the financial crisis?

Even later, when things were already getting better, because I remember that for the first couple of months we were able to pay the rent even without the support of the SCCF [the Latvian State Culture Capital Foundation – Ed.].

Do you have a commercial element that would allow you to stay afloat?

We really don't, so when the SCCF support disappears, we’ll most likely close down. In that sense, we are not all that independent.

Are there any opportunities to make money with the material you exhibit?

Internationally, yes. We have had exhibitions where people from abroad write and ask about the prices of works, but the local audience is very hesitant and also quite conservative. Another thing that we would need in order to do something commercially is someone who really likes to network, correspond with people, and explain the art. I’ve come to realise that I have no interest in doing this. I do the minimum that needs to be done, and 427 is already one of the most internationally visible art spaces [in Latvia]. We send press releases to all kinds of international blogs and the like, but at the same time, the commercial aspect would mean even more intense networking. At the moment our recognition comes more from the fact that we have peers – other places, artists, and institutions – that like what we do and who support us.

Are you and LOW Gallery the only small artist-run contemporary art galleries in Riga?

RIXC is also an artist-run gallery, but they are interested in media art, which is not our field of interest. I prefer the classical mediums in a new context and in conjunctions – painting, drawing, sculpture, installations.

My personal opinion is that artists are free to do whatever.

Are the identity wars and the current polarisation of thoughts affecting your work as well?

Not yet. This is perhaps because Latvia is, to a large extent, provincial, but neither are we offering on an international level anything ambiguous concerning this abnormally large number of identities. I don't think it's very interesting. My personal opinion is that artists are free to do whatever. Actually, it seems to me that this discussion is being used to distract from more important things. Now that American politics have become much more boring, I am happy to disconnect from the news on the internet because to a large extent these issues originated in American politics. And fortunately, this hasn’t come to Latvia in any significant amount.

Different Room, at the exhibition "Sound We See. Space We Hear" at the 2020 Cēsis Art Festival, 2020

You’ve mentioned several times that you like the lo-fi sound and an unconventional perception of sound. Have you worked with sound art?

Different Room, for which I’ve been nominated for the Purvītis Prize, is in some sense a sound work. The question is what you mean by sound art – a certain aesthetic, or simply the fact that sound is used. I have had no reason, and no desire, to create pure works of sound art as multi-channel installations – even though they still do interest me. But sound, as such, almost always appears in my solo exhibitions. Most often, a [sound] loop is played in a spatial arrangement. In the case of the work in Cēsis, my whole synthesizer setup that I use daily to make music was arranged on the floor. The equipment was connected and working at all times; a single sequence of sounds was playing live. Of course, from time to time someone from the public would come up, turn a knob, and the sound would change. I liked that the audience participated in the process. At times, however, they’d change it to the point that it no longer sounded good. There will also be sound at the [Latvian] National Museum of Art. I do hope that there the visitors don’t touch the knobs as much.

Was sound a curatorial requirement for the Cēsis exhibition?

Yes, it was basically an exhibition of sound art, not just a visual one. In the end, I added a context in which to listen to the sound. It is a small, crowded, and very insulated room with “Elektrotehnika” speakers and a good bass that you could really feel when entering the room. A very immersive experience. In the Purvītis Prize exhibition the sound will be different because I will not be able to exactly repeat something like that for a second time – I also didn’t write down the order in which I aligned all the synthesizers.

Visually, I like to do something that not everybody would call being in good taste. To be honest, I hate tastefulness.

Were you surprised that your work was nominated for the Purvītis Prize?

It wasn’t a surprise. This work is perhaps less abstract and more visual, not to mention its immersive aspect. Those who came to Cēsis felt the room – the sound, its cramped size with paintings and sketches… I think it was a very physically perceptible work. It seemed aesthetic enough in a visual sense as well. Visually, I like to do something that not everybody would call being in good taste. To be honest, I hate tastefulness. That’s why for many of Latvia’s art aficionados, my works have often been too technically incomplete, too brutal, and carelessly done. On the other hand, while studying at the Academy of Arts I came to understand that in Latvia, technically good execution is very important. And to some extent I still find the composition and technical level of of an artwork to be important, however, it doesn't worry me too much anymore, at least not in a standardised sense. For me, the main thing is that something is happening. Over the years I’ve arranged exhibitions in very different spaces – even in conditions that were completely unsuitable for exhibitions. One exhibition was at the K. K. fon Stricka Villa in complete darkness, in winter, without any heating. I Didn't Have Wi-Fi and That's Why I Started Painting was the name of the exhibition. Inspiration also came from the surrealists. In 1938 the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme took place in Paris – when the lighting for the installation in the main room did not work on opening night, Man Ray, who was responsible for the event’s lighting, handed out flashlights to everyone at the entrance. I try to adapt to every space, and how much finishing a work has or hasn’t had is not something I worry about. I’m more concerned with other levels of finishing. The space lives on its own. 427 is also changing all the time. Small things – like how the floor is increasingly wearing down… The walls have been repainted, and there are holes and stains. The back room is constantly changing – a small art collection is forming there.

That's being honest, and without any embellishment.

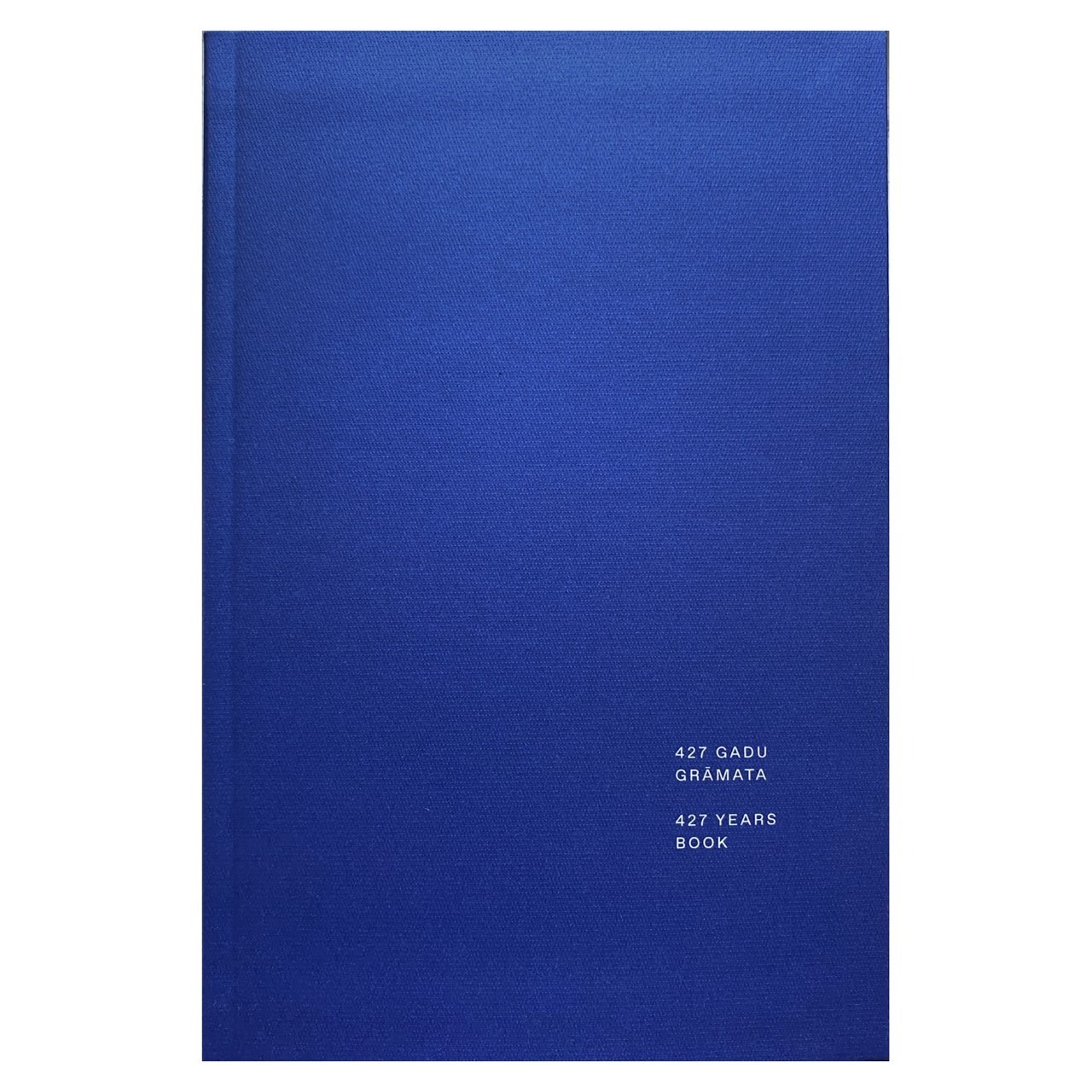

It is living – living with art. In the back room there are some pieces that people have left behind or that have somehow ended up there. The back room is constantly changing – light objects and furniture keep appearing. I like how that room is living. We've been in this space for five years, and over the years all sorts of things have taken place here. This can be seen in the 427 anniversary catalogue (The 427 Yearbook). Traces have been left behind by people, like the tags drawn by Labais Dāma [an experimental musician – Ed.]. We recently specially preserved that part of the wall to leave the tag intact.

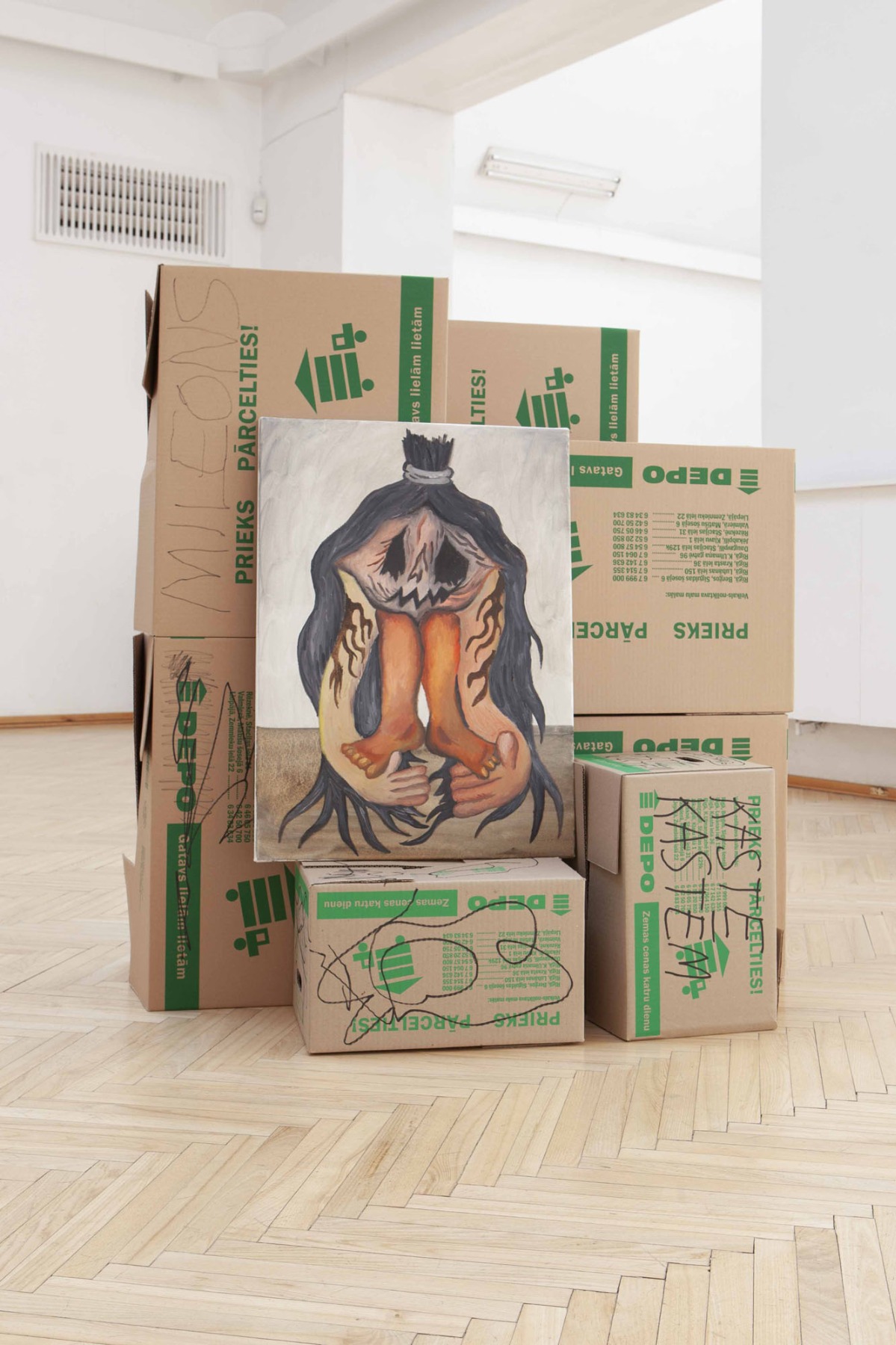

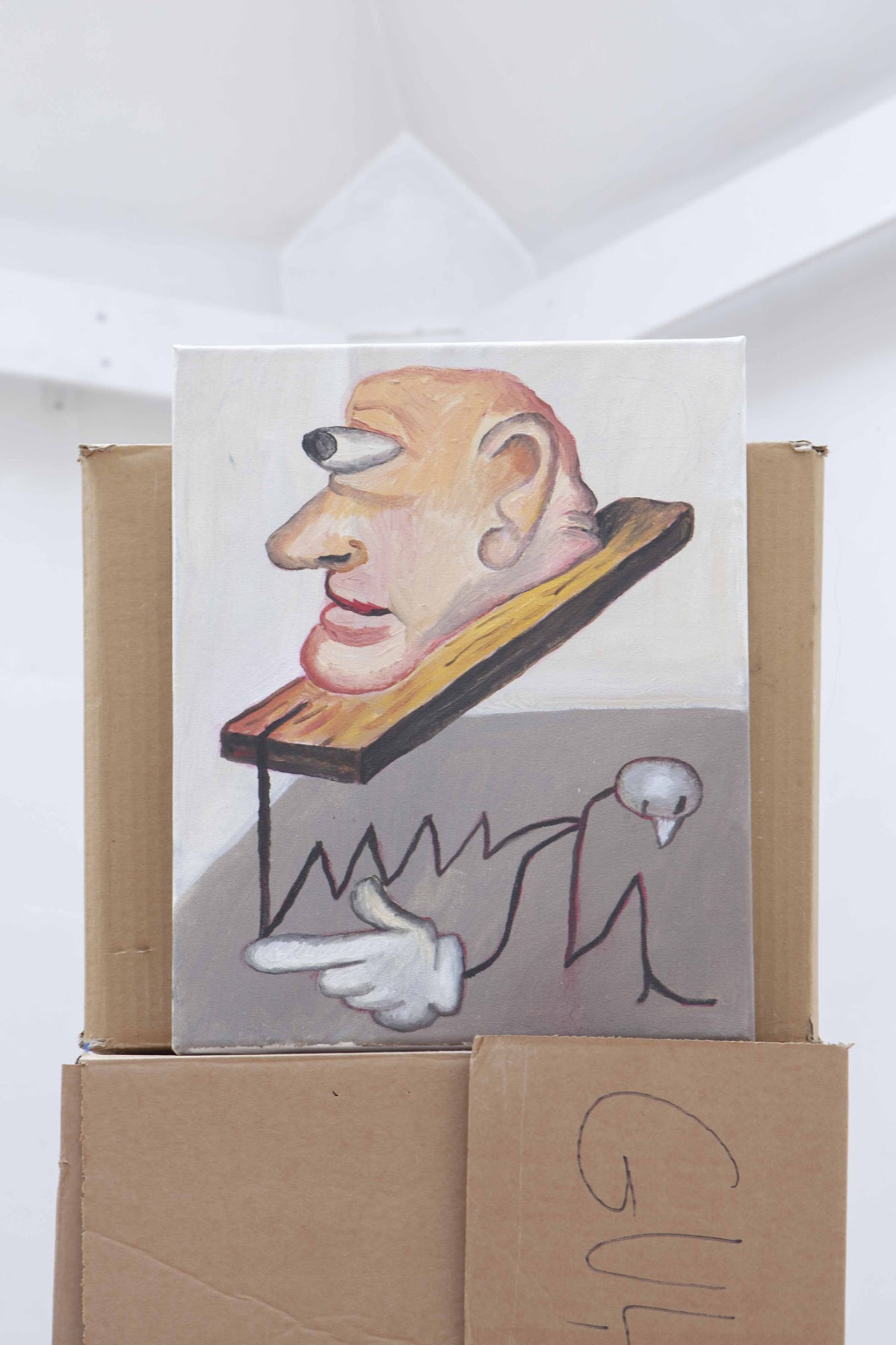

Kaspars Groševs, Demons and Ashes, 2019, exhibition view, Madona Local History and Art Museum. Photo: Līga Spunde

Apparently the people who nominated you for the Purvītis Prize considered it necessary to show respect for such art.

Incidentally, I’ve rarely had solo exhibitions in Riga. One of my favorite exhibitions of mine was at the Madona Local History and Art Museum during MABOCA [the Madona Bunch of Cool Art festival – Ed.]. Thanks goes to Margrieta Griestiņa, who worked there for a time and included me in the programme. The space there is excellent. The exhibition had no budget to speak of, and as is often the case in rural museums, the walls cannot be drilled into and the paintings must hang by strings. I really don't like that. It might be mocking to do that in a white cube gallery, but it's always terrible if done in a museum. I knew that I wanted to exhibit paintings in the exhibition, and I was trying to figure out how to exhibit them so that I wouldn't have to drill into walls or hang them on strings. So I decided to arrange the paintings on "Depo" cardboard boxes. That's a very cheap and practical material, but I like simple solutions to complex problems. Of course, the cardboard boxes “gained” a layer of writing, and the paintings themselves were strange and ambiguous. The boxes also formed the space and how the viewers moved through it. In that way, they also served as the scenography for the exhibition. You don't have to do much to make an exhibition good. A bus had been chartered from Riga, and they had obviously partied pretty hard on the way over because everyone arrived drunk and just in time for the last ten minutes of my opening (it ended at 2pm). Meanwhile, during the first three hours of the opening almost nothing happened – maybe ten locals showed up. Since the exhibition was held right before Easter, the museum, befitting a proper Christian town, was closed during the weekend. Basically, the exhibition couldn’t be seen for most of the time that MABOCA was taking place. In the end, it became an exclusive event seen by only a very small number of people. I think there were attempts to nominate me for the Purvītis Prize for this exhibition as well, but since barely anybody went to Madona to see it, only a few experts had actually personally seen it.

You don't have to do much to make an exhibition good.

Kaspars Groševs, Demons and Ashes, 2019, exhibition view, Madona Local History and Art Museum. Work "Bitcoin Millionaire", 20x30cm, oil on canvas, 2019. Photo: Līga Spunde.

Ojārs Pētersons [artist, professor at the Art Academy of Latvia - Ed.] was there.

He was also a participant.

He’s greatly contributed to the promotion of contemporary art in Riga, hasn't he?

He’s always urging that something needs to be done – directly practical activities. He believes we can talk and discuss, but until someone starts doing something, there’s no sense in even talking. We should only talk once we’ve done something. I think his attitude also instilled in me the need to start doing something at some point. Maybe it will turn out wrong or different than most people expected, but that doesn’t matter… There were various expectations for this gallery as well. Everyone projected their interests. Over the years the preconceived notions of only a few have probably come true, because a gallery is both a controlled and uncontrolled process. On the one hand, we only work with artists we want to work with, and we almost never exhibit anyone who has independently asked to be shown. Through physical and virtual journeys, we look for continuations of thoughts we have already begun. That’s why the programme is planned well in advance, but from time to time there are some spontaneous events, like when [experimental artist collective] GolfClyderman took over the gallery while I was in a residency in Prague, and the concerts performed here by TV Moscow, Kodek, and others.

You can answer or not – what do you think is the function of art?

Well, I don't really know anymore (laughs)… For a time, when I had just opened the gallery, I really felt that art had the power of presence and that the magic it has is that it doesn't speak to you as directly as music or theatre, which have words, rhythm, and powerful expression techniques that immediately pull you in. With art, especially the kind that can be seen in our gallery and also in my exhibitions, is that sometimes you come to see it and – there’s not much there. Or there is, but you don't really like how it looks. Sometimes there is no text, sometimes there is some text. Contemporary art in particular, including the kind that I like, often returns to the abstract – to the same 60s, to all sorts of experiments and materials. And that’s why it's not something that immediately interests or attracts people. You either have to become an art lover gradually, viewing art with sufficient regularity, or else you don't like it and are not interested in it.

You’ve just separated different genres of art – what is the overall function of art?

If you don’t separate the genres, you could also be talking about the art of cooking.

Not that. What unifies all art genres?

For example, music – and the same can be said for visual art and theatre – can comfort you and move you. You come and look at a shitty abstract painting and it might bring you to tears. An art gallery is a place where an emotional experience can occur, or, it can not occur. Any form of art can give you the impetus to think and look further.

Any form of art can give you the impetus to think and look further.

How is it different from religion?

From religion? Well, yes, art must also be believed. There are the basic things – either give energy or absorb energy, inspire, elevate. Visual art is a thicker onion, one where you have to peel through several layers to reach emotional catharsis. Art appears to respond to some sort of basic needs. Even when watching TV, you’re consuming the work of an artist because each show has its own production designer, its own visual editor. It’s the same thing when you buy a Snicker’s candy bar. I am now explaining to you much in the same way I had to explain to my father (as we sat in the local public sauna) why I had just enrolled at the Art Academy (laughs). Art can be anywhere. It's not just going to a classical music concert, or an incomprehensible experimental art exhibition, or a theatrical play where everyone cries. It is much broader than that. Even in a piece of clothing – there’s a tiny piece of art everywhere.

A tiny piece, yes. But there’s probably a boundary between design and art?

Of course there’s a boundary between design and visual art, but I also think that design is very creative work. It can make historic changes in how we perceive things. Exactly the same kind of power as there is in visual art or music. Of course, if we’re talking about my art, then that’s a much narrower slice of art – it differs from design, illustration, academic art, etc.

You enrolled at the Janis Rozentāls Art High School relatively late. Does that mean you had an alternative choice?

There was no Plan B at all. After finishing the 12th grade, I didn't know where to go study. I wasn't very interested in anything at that moment. And when I had started at the art high school, thanks to the rather intense schedule – you’re always painting, drawing, studying, learning computer programs – I had no time to think about possible alternatives.

Did many of your art high school classmates become artists?

Relatively few did. They’re working in all possible professions – one girl even became a doctor. But my year was a vibrant one – Evita Vasiļjeva, Darja Meļņikova, Krišs Zilgalvis, Oskars Pavlovskis, Artūrs Bērziņš, and a few others who are still active in art and design were all in my year. We were a good year – someone was crazy in one way, somebody else was crazy in another way...everyone pulled each other up – that’s the cool thing about getting into a good year. Even now, as a teacher at the art high school myself, I see that there are good years where they pull each other up and noticeably raise the level of the class as a whole. Such good chemistry occurs usually only once every four to five years, but when it does happens, the class is a good one and all of the teachers agree on that. And such years usually produce more graduates who continue to go on being active in the arts.

How do you currently feel about Riga – what do you like about it, and what do you think it lacks?

Hmmm… In fact, I probably like Riga very much. When I was growing up, I didn’t like Imanta much – even though I didn't care where I lived as a child. I liked that the forest was close, the air was relatively fresh, and living on the outskirts of Riga had a bit of a countryside feeling to it, but civilisation was also nearby. I've been living in the city centre for about 15 years now, and of course I associate Riga more with the city centre, which I do like. Not only is the art situation improving, but Riga is also becoming more interesting. And no matter how debatable, say, the new creative quarters and alternative cafes popping up everywhere are, there still is a lot left to do in Riga and Latvia because a lot is still lacking. For example, an artist-run gallery like this one was something that was missing in 2014. When we opened it, several people told me that they had had a very similar idea but never did anything about it.

What is lacking in Riga, and what (if anything) is different in Riga compared to elsewhere?

There definitely are different things. Even the same “Bolderāja" cafe on Avotu iela. I take every foreign guest to "Bolderāja", and one out of two say that there no longer are such places in their city. Or the old, dilapidated cafes that used to be on every corner. There is a healthy chaos in Riga – not everything has been gentrified and turned into a calculated system. The new Riga City Council is working differently, but the healthy chaos of Riga still remains – and this is actually the case throughout Latvia. At times there’s despair, as it is now concerning the financial aid and everything related to COVID-19, when many are once again completely disappointed in the administration’s abilities. But in general, this chaos, especially the chaos of Riga, amuses me more than it annoys. I like the peculiarities of Riga, the bad air, the kind of districts we have. We purposefully moved to the Avotu iela area from the Moscow district [of Riga] because, even though it was interesting being there as well, people from the centre and other districts did not want to go there. It is interesting for everyone to come to the Avotu iela area because there is always something going on in the area, although it is inevitably being gentrified as well. Right next door there will soon be a new fancy bar – it’s owned by the “Cēsu alus” conglomerate but not advertising this affiliation and instead pretending to be a small micro-brewery.

I take every foreign guest to "Bolderāja", and one out of two say that there no longer are such places in their city.

Is there anything else that distinguishes Riga from other cities?

Maybe the differences between cities is more of a psycho-geographical thing for me, but Riga is quite different from even Tallinn or Vilnius, never mind other cities. Every city is different. Riga’s “vibe” is very encouraging.

Passive but encouraging.

Yes, passive too. Especially now, during Covid, everyone in Riga is very withdrawn. And that’s not conditional on the current restrictions. I was in Amsterdam in the autumn, and everything there was also closed, but there still were small things that gave the feeling that something was happening. Nevertheless, it didn't feel like [Amsterdam] was a place where I would like to live. Maybe because over the years I’ve gotten to know everything in Riga – you have a psychologically special feeling about every street and quarter.

You have had exhibitions abroad. Do you feel that your work, including the 427 gallery, is perceived differently outside of Latvia?

Foreign exhibitions are different every time. I don't know how art is even perceived… The people whose opinion is important to me in Riga – yes, I like the way they perceive my art. But when you go abroad, you may hear different kinds of feedback; people are more likely to refer to something that is more familiar to them. Either on a local or international level. Yes, knowledge levels vary. The average visitor to a Western exhibition is better informed because they have seen much more. But not always. In November there was a 427 exchange event in Amsterdam with the local art space P/////AKT. It was the Artist Crisis Center, which we created together with Elīna Vītola and Ieva Kraule, two of the gallerists from LOW Gallery. One of the elements of the exhibition was me, as an employee of the crisis centre – I hung out in a corner of the space, painted, drank coffee, and also talked with visitors. I was there for three or four weeks and met practically all of the visitors to the exhibition. Of course, many who came were very educated in art, but there were also some who just seemed to watch and listen, and you realise that you could see such people anywhere in the world, including Riga. The average level in the West may be higher, but in general, artistic reactions are similar everywhere. By and large I didn't feel that there was a big difference between being at the exhibition in Amsterdam and, say, an exhibition at the Latvian National Art Museum in Riga, where I might have to talk to children more. It appears that in Latvia people take children to museums more than elsewhere. That also gives one hope that future viewers will be more open-minded.

Kaspars Groševs, Demons and Ashes, 2019, exhibition view, Madona Local History and Art Museum. Work "I Told You I’m Not Good", 50x70cm, oil on canvas, 2019. Photo: Līga Spunde

Who is 427’s target audience?

Young people, 17–25 years old.

Art students?

They are as well, but more often people without any connection to art, and who see that here is something they have only seen on the Internet and elsewhere.

The only thing I've been listening to for many years is Gavin Bryars’ Jesus' Blood (never failed me yet).

What is your favourite music that you can immediately name, without even thinking about it?

The only thing I've been listening to for many years is Gavin Bryars’ Jesus' Blood (never failed me yet). It’s based on a sample he recorded of a homeless person. It’s a 50-minute-long piece consisting of a religious stanza sung on loop with orchestral instrumentation recorded over it. I was listening to it about six months ago and bawled during half of it (laughs). I also like very “cheesy” music – lately I've been streaming the same old nu metal, like Korn or Deftones. I also like Dutch “hardstyle” – super-melodic and euphoric hardcore pop at 180 beats per minute. Like, for example, Scooter's new single FCK 2020. I like older club music tracks, party tracks that haven’t been overplayed and heard for a long time – they’ve taken on a new emotional weight. Early pieces by David Guetta and other cringey DJs. At the same time, I’m mostly listening to good music from the 70s to 90s – what they play on NTS, the radio station that I listen to from morning to night. Sometimes there’s stuff I don't like, but by and large I have no objections to what they play. Be it stoner rock, minimal synth, grime, or Balearic house. I listen to EVERYTHING.

I’ve been told that when the antique shop "Lira" was still open on Baznīcas iela, you were a frequent customer – leafing through their vinyl records, and especially interested in music from other cultures.

Yes, I have a collection of cassettes and records, and it's mostly folk music – usually from Africa, but also folk music from Europe and all sorts of marginal recordings, including records bought at various Skaņumežs festivals. Then I have my old cassettes, as well as cassettes that others have simply given me or brought back from their travels. For instance, homemade recordings from Kamchatka or some local ballads from Venezuela. I like weird and rare recordings.

Music is much like art to you, isn't it? – A conceptual interest, but one that isn’t abstracted from life.

Definitely not abstracted. The very method by which a record or a work of art finds a place in my collection unifies them. The same goes for self-reflection. Sometimes I make music, then I forget about it for 10 to 15 years, and then when I finally listen to it again, I think it sounds quite interesting – that it could be continued or used in some way. For instance, the cassette recordings I made as a teenager – which was breakbeat in the style of Prodigy – I’ve sampled and put into modern rave tracks.

Can I listen to them?

They haven’t been released anywhere. All my music that is not improvisation nor recorded in the process but has been saved on the computer and sequenced, has not been released anywhere, basically.

Can’t you put it on Bandcamp or SoundCloud?

I want to finish it. On Bandcamp there’s the project Figūras, which I recorded live and then maybe compressed and equalized a bit without changing much. I dump everything that I make in there. But the music that I’ve produced and refined has not been published. Nothing is complete; it all still has to be finished. Right now I finally want to create and publish something new. Labais Dāma and I have a small cassette label called No Sex, Just Talk.