Residents of the Blue Lagoon

A conversation with Kaspars Groševs and Evita Vasiļjeva shortlisted for the Purvītis Prize 2023

Evita Vasiļjeva and Kaspars Groševs have grown up in the same artistic environment, the creative paths they pursue sometimes parting and then intersecting again in different cities, exhibitions, and embodiments of their ideas. This time around, the meeting place is the ‘Blue Lagoon House’, made together and at a leisurely pace, filled with direct and indirect references to Hardijs Lediņš and NSRD’s* ‘approximate art’, finding a new appreciation for local art communities through utopian thought projections and the confluence of materials.

Evita Vasiļjeva and Kaspars Groševs, ‘Blue Lagoon House’, 2022. Exhibition view at the Cēsis Contemporary Art Centre

Evita Vasiļjeva is a Latvian-born Europe-based artist, educated at the Department of Visual Communication of Latvian Academy of Arts (2005‒2009) and the Amsterdam Gerrit Rietveld Academy (2009‒2013), without a permanent residence at a specific address in a specific city. True to this spirit, Evita arrived for this interview armed with a suitcase to head straight for Cēsis where she and artist Kaspars Groševs are mounting an exhibition entitled ‘Blue Lagoon House’ as part of the 2022 Cēsis Art Festival. The next stop is the Lyon Biennial.

‘A teacher once said that artists make things they did not have as children. I’m not sure if I should believe her or not. I didn’t have a room of my own as a child in Soviet times. Perhaps there is some connection with my art. Or perhaps [the fact that] I don’t have a real home; I don’t have a flat of my own in one specific country and city [is the reason why I] always set up my own room in every exhibition. I am in Latvia now, but my thoughts are already with the basement in Lyon,’ she says during our conversation.

Speaking of Evita Vasiļjeva’s sculptures, critics sometimes refer to them as ‘a physical extension of thought’. At the same time, it is important to highlight the multi-layered character and architectural depth of her art, the infinite labyrinth of thoughts where the viewer is invited to search for his or her own unique experience amidst robust and rough fragments of concrete, vibrations of light and fragile spheres of soap.

Monumentalism and physicality of corporeality, tangible even without touching, are the most significant qualities that define her art, as is existence in an intermediary state, a certain incompleteness that generates a sense of openness. Evita has developed her own language, always recognisable on sight. And if you don’t know her, you could easily think that her art was created by a man. ‘It’s just that I have never wanted to make typical women’s art ‒ the kind associated with women by the viewers. I have thought a lot about these matters because the subject has been quite topical in recent years. Women are fully able to make anything, build anything.’ Evita makes her artworks with her own hands, getting some help when needed. And it is a surprise in the routine of Western European art today because ‘it does not happen like that anymore’.

Kaspars Groševs is an artist and curator who has participated in many international and group exhibitions and has held several solo exhibitions. The first of them, ‘I/O. Without Enemies’, was shown at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre in 2011. In 2014, he created and until now manages his own non-commercial gallery – 427. He has been the curator of several international projects. He graduated from the Department of Audio-Visual Media Art with BA and MA degrees in visual communication. The fusion of music and art is a frequent phenomenon in his art. And as he himself admits to Viestarts Gailītis in an earlier interview for the arterritory.com: ‘I really like the “substance” of music, and I have always liked to experiment with different instruments – cassette players, reel-to-reel tape recorders, old organs. Only now have I become, so to speak, more modern, making music with various synthesizers and a computer… Art, on the other hand, I have always approached with conceptual, Fluxus-style ideas, with hidden or subjective jokes. But in art high school, in some masochistic sense, I also really liked painting – a class that many students did not like. I loved creating shapes and textures with oil paints. At one point I also liked to create different technique experiments on paper – gluing, spraying, burning, painting, and drawing with different kinds of markers, pens, etc. This also logically connected with my musical activity – namely, my approach to both music and art has a certain procedural nature to it. In music, it’s improvisation. As soon as the instruments are plugged in, the signal sounds and it is sometimes unclear where the tuning ends and the playing starts. It’s similar in art – it is not always clear where the “tuning” ends, at what point a “piece” has been created, and at what point is it already just an encore.’

Evita, you have been living and working outside of Latvia for a long time now. Does your background make you different? Is your art different? Are you a cosmopolite or an Eastern European artist despite everything?

Evita Vasiļjeva: Both. The longer I live in Western Europe, the more I feel like an Eastern European. Differences become obvious through exchange/diversity. I have by now mastered all the codes of being a world citizen, and people struggle to tell where exactly I am from. I installed my work ‘Bed-Room-Bed’ (2021) for the ‘Adesso No’ group show a month ago in Florence, at the Not A Museum exhibition space; it is made from metal beds, and the curators were very surprised to learn that I had made the piece with my own hands, I had done all the welding myself. They were shocked: ‘It does not happen like that anymore.’ Normally you give somebody the drawing and they weld it for you. I don’t do that; I find it very normal to make your own things. I recently talked about that with Liene Pavlovska ‒ about which artists do it themselves and whether it is important to make things with your own hands. I think it might be about some cultural layers in your identity. I am half-Russian and half-Latvian. My Russian grandmother, my babushka, worked insanely hard. That’s how I was brought up, with this idea that you have to do everything for yourself. That’s what I normally think ‒ if you cannot buy it, make it. I think it can be traced back to the Soviet times when everything was always remade and adapted; nothing was ever thrown away; everything was treated with creativity and lots of sticky tape. And there was great respect for hard work; the idea that you had to work was cultivated a lot. It is this kind of unconscious baggage that is hard to get rid of.

Evita Vasiļjeva. LITTLE SOAP OPERA. Soap, flies, pigments, thread, dimensions variable

Do works preserve an energetic imprint of the artist?

E: Yes, I believe in that. The presence of the artist’s hands can definitely be felt.

The ‘Blue Lagoon House’ is a result of artistic synergy, but it is not your first creative encounter.

E: We were in the same year both at Rozentāls Art School and at the Department of Visual Communication of the Art Academy of Latvia (2005‒09). Our first contributions to various group exhibitions date from around that time. I think the first group exhibition we had was in the Old Town of Riga with our fellow students at the Viscom ‒ in a store that was being redecorated. Then we had our graduation show entitled ‘Rent 00-10’ (Noma 00-10, 2009). Kaspars showed a video where he was running in a forest and gradually disappeared, and I had flowers made out of sausages; they were filmed and projected on the wall and looked very much like real ones. And finally, our early solo exhibitions at the Kim? Contemporary Art Centre, in Spīķeri Quarter (2013), coincided in time. For some reason, we somehow seem to be working parallel to each other, each on his or her own side, but quite nearby each other. We also made an anti-drugs animation short together, ‘I Said Yes / Was Entrapped’.

Kaspars Groševs: Basically, it was Evita who convinced me to enroll at Rozentāls Art School; I was not really sure what to do next before that. I tried to get accepted at the Applied Arts School but failed, of course. And Evita made this whole romantic thing of Rozentāls School sound so tempting that I decided it would not hurt to learn some drawing and painting. We studied together and egged each other on, living in each other’s pockets. When Evita left to study in Amsterdam, we didn’t lose touch ‒ we kept meeting up quite regularly, corresponded, and shared impressions, information, reflections, experiences, and all that stuff.

Evita Vasiļjeva and Kaspars Groševs, ‘Blue Lagoon House’, 2022. Exhibition view at the Cēsis Contemporary Art Centre

How would you describe your experience of working together now, mounting a joint exhibition?

E: We both trust each other and give each other total freedom to make our pieces as we see fit. I think of it more as working alongside each other. Of course, we regularly share information on what each of us is making ‒ to make sure that our pieces are mutually complementary. Kaspars and I have similar thinking about art; about what we like. Community spirit is quite important to me. In every exhibition. Even if I feel like a very distinct individualist, the team, getting people involved is essential for me.

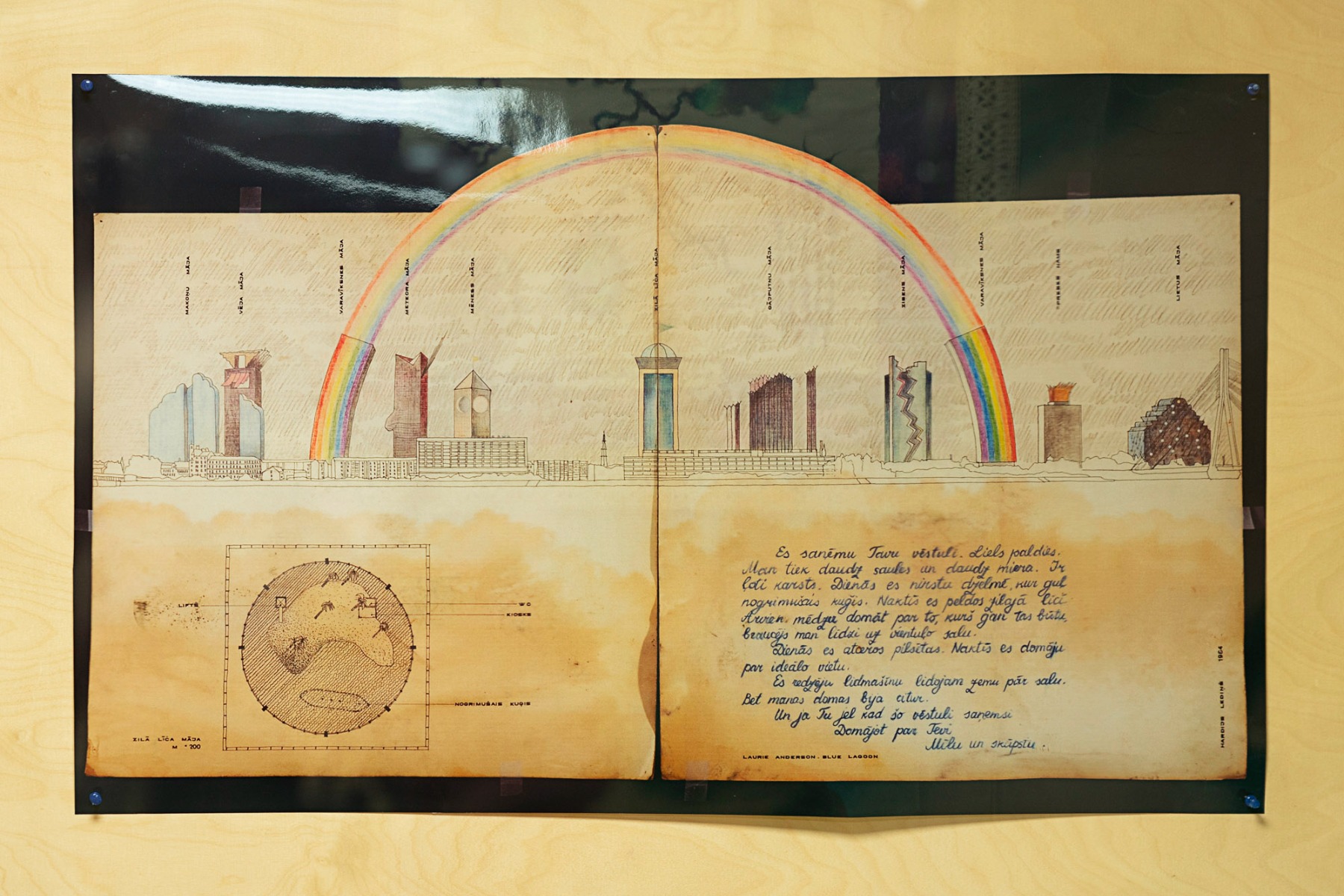

K: I think that in this case we also share the same references which each of us processes and uses in our own way. The reference to Hardijs Lediņš’s drawing provides something like a conceptual framework or an ‘approximate’ map (resonating with the practices of ‘approximate art’) while, at the same time, giving us creative freedom. The actual exhibition space also definitely determines a more specific direction; the materials, light, sound ‒ all of that is already present but we work on bending these settings and adding our own imprint to the whole thing.

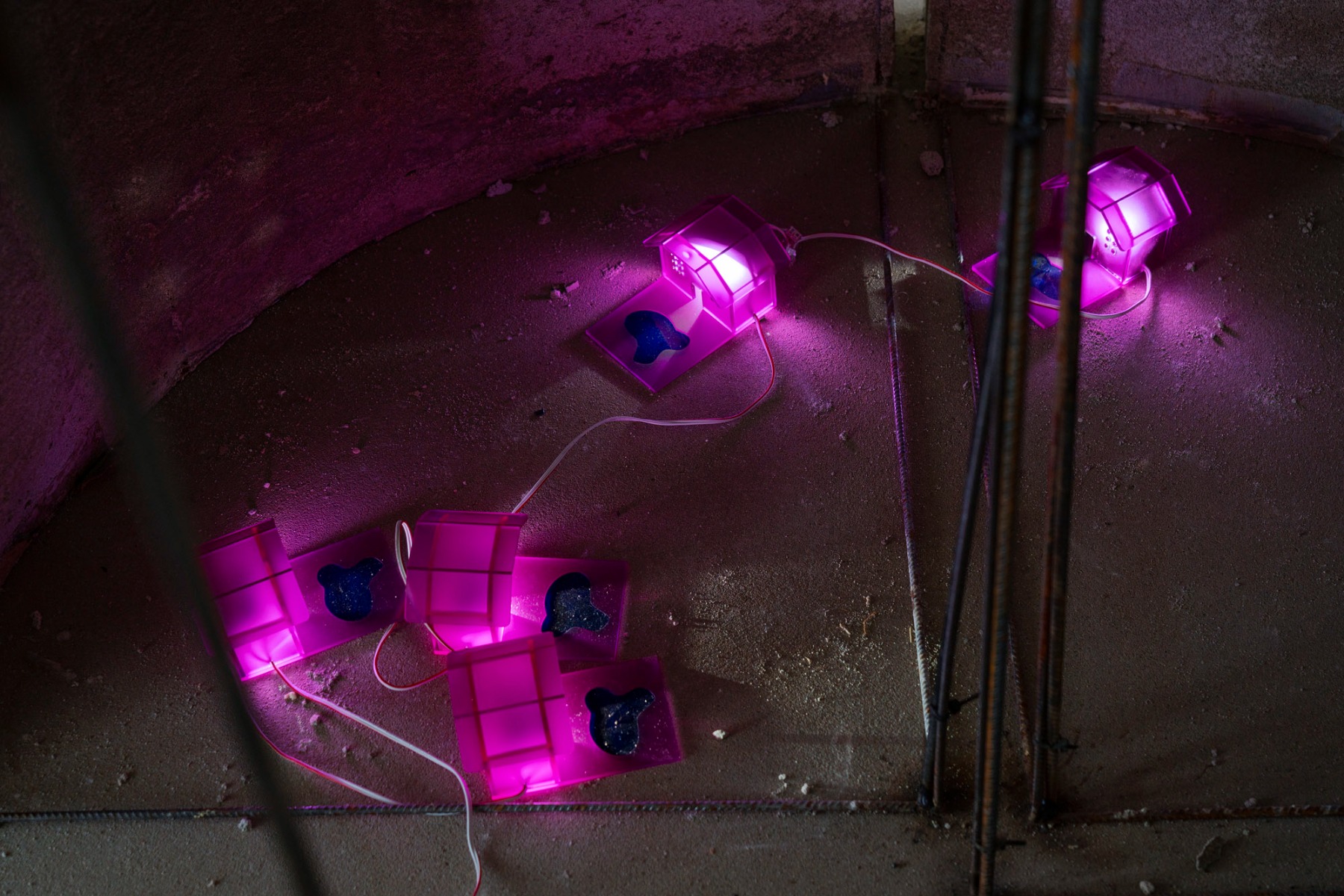

Evita Vasiljeva, Bell, 2022, Steel rods, concrete, LEDs

During the lengthy process of acquiring concrete shape, the ‘Blue Lagoon House’ has undergone a certain transformation ‒ both in relation to space and time and possibly to changes in global and personal everyday life. Could you tell me a bit more about the journey to its current image?

E: When I am making an exhibition, I never know what the result is going to be like ‒ not until the very last minute. Working on a computer or sketching without regard for gravity is one thing. But time goes by, and physical considerations also have an impact on the result. I think I was particularly strongly influenced by the war. I was in Morocco at the time and was terribly upset. Suddenly it seemed that everything had changed, and nothing would ever be the same as before. Friends took me to the beach to get some air and shake it off a bit. I changed the sketches completely after that, introducing the current idea of the Bells with a reference to sand buildings, impermanent utopian architecture, and the fragility of time. The title of the exhibition was known to both of us all the time and has never changed; what changed was our thoughts or approach to what the Blue Lagoon House was.

K: It is true that the first ideas were born a year and a half ago; forms have changed over time but the ‘presence’ of Hardijs Lediņš and NSRD from the outset provided an approximate field of ideas where we could roam and think about our works. For instance, the idea of tape loops of varying lengths floating among Evita’s work and marking the space with ethereal eeriness was already there from the very beginning. Over time, Evita’s work acquired more defined outlines; my video with blurry images of Riga’s creative scene appeared. Last year’s experiments with oil and acrylics also found their place in this field of ideas. The closer the opening date, the better-defined outlines emerged for the exhibition.

Evita Vasiljeva, Bells, 2022, Steel rods, concrete, LEDs

What about concrete? The material springs to mind when I think about your works. Also, in the context of the ‘Blue Lagoon House’.

E: I started working with concrete back in Amsterdam, during the De Ateliers residency (2014‒16). Before that, I worked with plaster. The floor was grey at De Ateliers, and I realized that plaster will not look particularly good in that room. Everything happened quite organically. Without much deliberation. They started referring to me as ‘the strong Russian woman’ after that (laughs). Overall, it seems that the point of departure for the whole thing was a kind of Eastern European code, the post-Soviet legacy. I am starting to think that there must be deeper roots for that. My grandfather was building a house with my dad. From the actual foundation. As a child, I spent a lot of time watching them; I saw the whole process. How they cast the foundation, how they buried the slab in the ground. I found it fascinating. I played with other children on the adjacent construction sites. We crawled inside the unfinished structures; it was our headquarters. A large part of the newbuilds was abandoned. They remained unfinished. Latvia regained its independence; a time of big changes started; many people lost their jobs. This stayed in my mind as a moment when time stopped. When some things were not continued. Or perhaps somebody else continued them but in a transformed state. That influenced me.

It is exactly this moment that we see in your bells for the ‘Blue Lagoon House’ in Cēsis: unfinishedness, half-finishedness, fragmentation…

E: Yes, the bells consist of segments, some of which are not completely filled. I also think about architecture and modular building ‒ about ways of putting something together. I also mostly use the modular principle ‒ forming a whole by joining separate things. But ‒ yes, preserving fragmentation. It makes a work... open? Personally, I always prefer works with open meaning. If I can simply read a piece, it is over for me. If I cannot read it completely, it continues to intrigue me. Build associations. But it is important to preserve a certain balance ‒ to not confuse too much. Because many people feel confused, they don’t get the idea and therefore reject the work. But there are others who do not understand and yet find it interesting.

Kaspars Groševs, SWIM #29 (DK), 2022, Oil on canvas

Kaspars Groševs, Moshpit, 2022, Oil, acrylics, spray paint on canvas

One of the objects on view ‒ the Lagoon booth ‒ was launched last year, late in the summer, inviting to attend public artistic and musical performances by local talents; these sets are also scheduled for the opening of the exhibition. To date, it seems that recognition, formation, and involvement of creative communities are playing a significant role in Kaspars’s curatorial and artistic practice. Could it be called a kind of mission? What is your take on the significance of creative communities in your practice?

K: Yes, seems like running the 427 Gallery has made me think more about the artists who are close to me not just geographically but also conceptually. It has helped me get to know or get to know better some very diverse super talented artists, and yet mutual support for and by the local scene has always mattered most. During the pandemic, we showed Latvian artists only, because it seemed that the artists who live and work nearby are much more accessible and real than the outside world ‒ which at some point turned literally virtual overnight. In my own work, I also tend to think more and more about various creative communes, starting to explore my own origins in the underground hardcore scene and the visual works created at the time when everything seemed so sudden and newly discovered. Images from the time overlap into the ‘SWIM (Someone Who Isn’t Me)’ series of paintings ‒ some of them more distinct, others more blurred or even disintegrated, like the punk who drowned in Madona, seen on the back wall. Some of the images are more recent; what they have in common are the various communes I have ended up in. It seems that these images also frequently influence the formal parameters.

Evita Vasiļjeva and Kaspars Groševs, ‘Blue Lagoon House’, 2022. Exhibition view at the Cēsis Contemporary Art Centre

E: I have always been interested in communes and groups as bodies of intellectual affiliation. While studying at the Rietveld (2009‒13), my fellow students and I formed an association called Last Minute Group; every Saturday, we made exhibitions for ourselves and for others. I remember it as a very important time for me; it was there that I came to understand that a collective possesses a very powerful force of momentum. After graduating from the Rietveld, I frequently changed places where I lived; I moved around mounting exhibitions and had no chance to join collectives ‒ I never stayed in the same place long enough. In 2020 Kaspars invited me through the 427 Gallery to take part in an exhibition in Paris; it was called ‘Hotel Normandy by The Community’ and was mounted by The Community collective. It was when I tasted the collective flavour again and felt a powerful rush of energy, inspiration, and a sense of belonging. The exhibition was held in a David Lynchesque spooky hotel near the Louvre. Rooms were transformed into experimental shows, each featuring an ensemble of musicians, a record label, or even a fashion collective. There was a very real taste of Zeitgeist and crude energy to the whole thing. The fleeting quality of the collective spirit marking space and time strikes a very powerful chord with me.

It has been frequently noted that one of the conceptual points of departure for the exhibition was Hardijs Lediņš’s utopian drawing of a Pārdaugava landscape, ‘Blue Lagoon House’ (1984), accompanied by text from a piece by Laurie Anderson (‘Blue Lagoon’, 1984). Lediņš’s art was largely revolving around utopian ideas ‒ but what is the role of utopia in art today?

K: I don’t think I would attempt to speculate on the ability of art to change the world for the better, but the experience of viewing art is definitely a thing that makes this world much more bearable and occasionally even enjoyable. Thinking of utopia, I tend to associate it more with certain ideas from the past and those utopias imagined in various times that frequently catch the sight of artists and curators these days. Because today even the idea of colonising Mars or something along these lines sounds more like an ominously bad-ending Hollywood catastrophe movie. It is a much more real thing to surround yourself with an environment where you can flourish and create among other artists ‒ a small micro-utopia that sometimes flashes by like a mirage before sunset.

E: Isn’t art the exact place to create your own utopia?

Evita Vasiljeva, Seven Reasons Why You Should Make Time for the Sunsets I-V, 2020-21, Soap, flies from Latvia, plastic, metal, pigments, wires, lamp

It has become almost a customary practice at Cēsis Art Festival for artists to work and create their pieces on the site, in Cēsis. What does the physical process of producing artwork mean for each of you?

E: My practice has accidentally developed in such a way that I mostly ‒ whenever possible ‒ stay and work at the location of each exhibition. I like to get a feel of the place by going to work every day, buying materials in local shops, and consulting the technicians. As far as possible, I try to collaborate with the character of the space right there, on location. It is important that the works I create interact with the environment.

K: In the early stages of my career I didn’t find the physical production of works interesting. But I unconsciously continued to develop my line and how it builds clouds of ideas. Later, when I had managed to forget the painting skills learned during my studies, I decided to start doing it again ‒ initially sticking with just the line which eventually acquired some flesh. In recent years I have once again rediscovered the joy of sitting in front of a canvas and painting; it must be the studio I have finally obtained after all these years that changed the process for me. Presently my favourite days are those when I can quickly get myself to the studio right after the morning coffee and stay there until the evening and, consequently, the opening time of the nearby bars.

‘Blue Lagoon House’ is a joint project between you two; however, you have also invited some other artists. What were the conceptual preconditions for this approach?

K: The Lagoon booth merged the seemingly different facets of various art communes, and therefore I decided to work with artists who would populate a temporary space as a reference to the Blue Lagoon House interior in Lediņš’s drawing where an island near the sunken ship houses a booth, a WC, and a lift. I think the unifying motif was transferring the NSRD ‘Walk to Bolderāja’ to the present day when ‘walking to Bolderāja’ means something different for creatives of various generations and professions ‒ namely, getting themselves to Avotu Street. This is where this sense of community is at its most powerful for me, because in a space of a single day people like Maija Kurševa, Ojārs Pētersons, $hady Ladies, Anna Malicka, and finally Rihards Lepers may all walk in.

E: It was I who invited Kamil Bouzoubaa-Grivel. I met him in Paris in early 2020, when covid had just started. He was at the Cité residency while I was at Fiminco. I liked his drawings. We discovered that we both loved weathervanes and decided that we should make one at some point. Kaspars and I had agreed early on that we would have a weathervane on the roof at the exhibition. The whole thing clicked into place quite organically, and I invited Kamil to make these things.

The show is interspersed with references to NSRD and ‘approximate art’. Which, for you, are the deepest imprints left by Hardijs Lediņš and NSRD, echoing in art today and in your upcoming exhibition?

E: I am a fan of NSRD recordings since my time at Rozentāls Art School. I think that the music is structured brilliantly. The Latvian language plays a strong role and gives a sense of belonging. Personally, I insanely love the way they feel their way and play around through sound, their open form, rhythmic construction, the openness of the language, and the universal thoughts that are simultaneously very exact and descriptive.

K: Yes, I think their music has had the greatest impact; it is harder to find direct references in the area of art (the artists’ collective Klīga comes to mind) because the things NSRD did were mostly performative and temporary. However, the absurd, humour and even light-heartedness that can be found in their videos definitely continue to reverberate in the works of various artists and, hopefully, in the exhibition as well. We also tried to capture some potential reincarnations of the NSRD energy ‒ in Evita’s architectural sculptures, in sound and video; there are some reflections of the Pārdaugva dreamed up by Lediņš in the paintings on the second floor.

The industrial space of the upcoming Cēsis Centre for Contemporary Art has previously been entrusted to larger groups of artists; this year, it has been handed over to you and placed under your artistic management. How do you experience the specific space and location ‒ has it influenced the exhibition and the featured works?

E: I definitely was influenced. Originally, I wanted to make my works from columns but there are already so many in this space in Cēsis. I changed my plans and decided to focus on the vastness of the space, the landscape-like horizontality, the presence of sunlight, and the currents of wind. The whole thing reminded me of a rotating clockwork, time that never stops ‒ and coffee is drunk every day.

K: Although I have been here many times before, the sheer vastness of this space took my breath away when I came back this year. It all started to seem more real once Evita moved in and started to inhabit the space. My room made me think about the media that could shape it ‒ not just paintings but also sound and video. It seemed natural to change very little of what had remained from last year and make myself at home in what was already here. The sunlight is wonderful, and it is cool when it’s dark.

Evita Vasiļjeva and Kaspars Groševs, ‘Blue Lagoon House’, 2022. Exhibition view at the Cēsis Contemporary Art Centre

What are the key motifs, sensations, and parting words you would want to impart to the visitor of your ‘Blue Lagoon House’ exhibition?

E: I always think of my mum ‒ how she will be worried about the things that I make and not understand what it is about. She is upset that she doesn’t understand it ‒ it makes her worry. I always try to calm her down by saying that you don’t have to understand anything – you can simply enjoy what you see. And then I ask her in the end: what do you think it is?

K: While working on the project, I caught myself thinking every now and then that Latvian art is so interesting right now ‒ more than ever. It added certain responsibility while also freeing the mind for thoughts about what should be done individually to make everything better for everyone. I hope this show will be a field of possibilities where everyone can pick up a thought, a texture, a play of light and shade, or anything else to consider or even continue ‒ like we are trying to continue and develop threads of thought from the past.

***

Invited artists at the ‘Blue Lagoon House’ exhibition:

0.0.01.0.0., Maija Kurševa, Anna Malicka, Dzelde Mierkalne, Luīze Nežberte, Līva Rutmane, $hady Ladies, Klāvs Upaciers, and Kamil Bouzoubaa-Grivel (France).

***

*NSRD or Workshop for the Restoration of Unfelt Feelings is a Latvian avant-garde, experimental, and underground music group founded in 1982 by architect, and multimedia artist Hardijs Lediņš together with artist Juris Boiko. NSRD was active until 1989. The composition of the group changed over time, artists, architects, musicians, fashion designers, actors, etc. worked there creating an alternative to the professional art scene of the 1980s and expanding the boundaries of art understanding, NSRD introduced several innovations relevant to the Latvian environment – experiments in various media and art sectors (performances, actions, video installations, photographs, video art, music, and lyrics), and also influenced the music environment development in Latvia and experimental demo recording culture.

The conversation took place on June 2022.

Title image: Photo: Kamil Bouzoubaa-Grivel