God’s Favourite Child

A conversation with Ance Eikena / shortlisted for the Purvītis Prize 2023

One of the youngest among the artists shortlisted for the Purvītis Prize, Ance Eikena studied sculpture and visual communications at the Art Academy of Latvia; she has gained wider recognition for her striking performances and sculptural objects.

Inspired by personal experience, her art serves as an intimate and sensitive way of recording the human existence; empathy is her instrument that helps draw the viewer’s attention to a range of social problems.

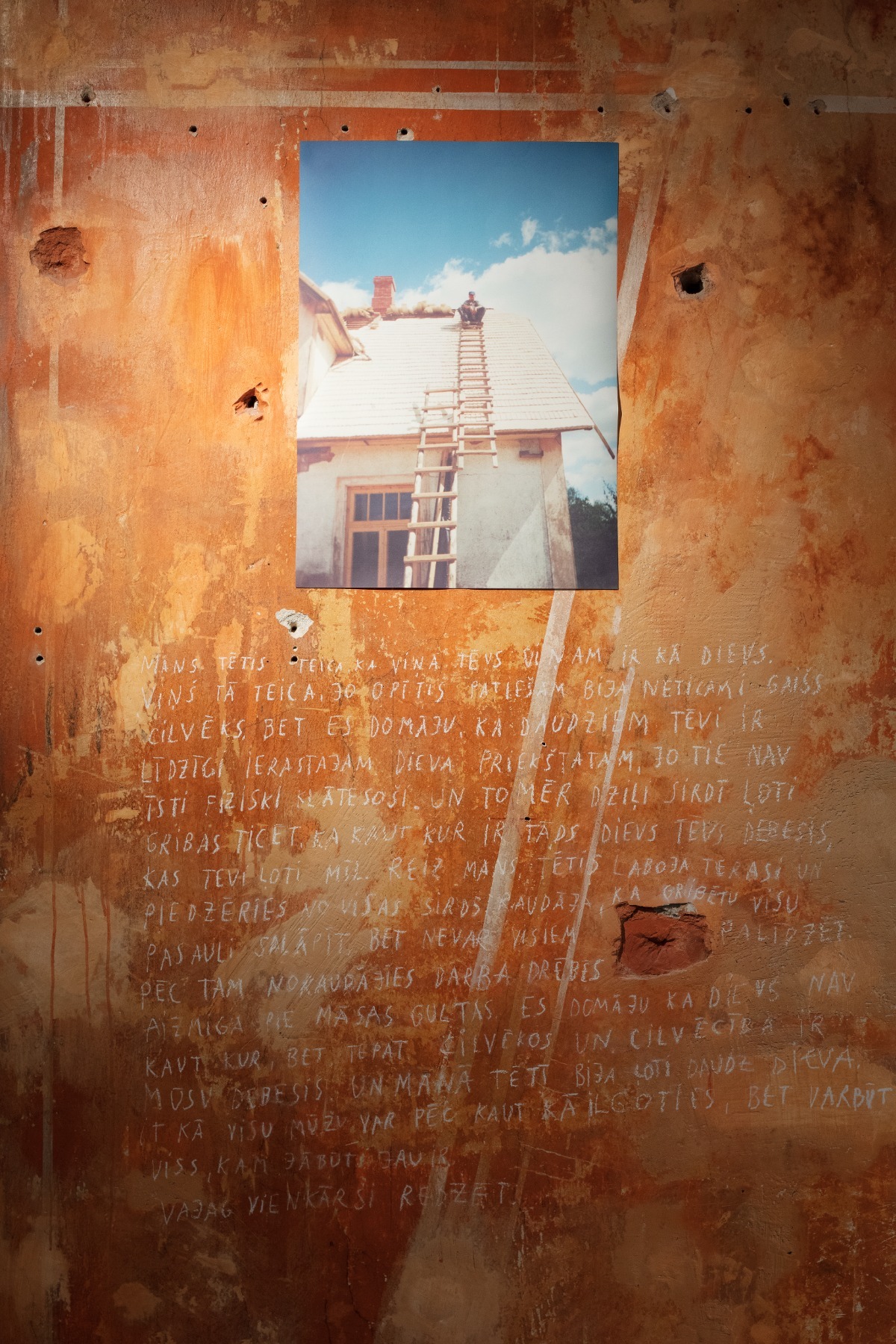

Ance Eikena’s first solo exhibition ‘Our Heavenly Father’, an autobiographical study of a father–daughter relationship, ran at the Brīvība Art Space. Objects created for the show alternated with documentary artefacts from the lives of the artist and her father. The set of the exhibition space aptly incorporated elements that are frequently present in the Latvian landscape – empty bottles left behind in room corners, stained rubber slippers and trousers, empty cigarette packs, clanking metal buckets. These somewhat embarrassing yet immediately recognisable symbols conjure up the reality of life in Latvia.

Avoiding a didactic approach of depicting and condemning the consequences of alcoholism, Eikena’s texts and altars reveal the internal contradiction that anybody suffering from this disease must deal with. The narrator created by the artist finds a way of detaching from a personal tragedy, transforming it into a more comprehensive discussion on selfishness, shame and premature coming of age. The blindness of this selfless love is revealed through the childish voice praising Father’s merits; meanwhile, the juxtaposed coarseness and shabbiness of the featured objects point at the beastly, egotistic and destructive nature of the object of this love. The dichotomy of the ‘Madonna and Child’, scrawled with chalk, and the picture of a man affected by disease explicitly captures the Latvian reality where the roles are frequently switched between the portrayed: the children often find themselves turned into ‘madonnas’ at an early age, while their parents become their ‘babies’ who need to be cared for.

The personification of God adds a human dimension to a statistic abstraction and a national tragedy. ‘Our Heavenly Father’ makes the viewer more human – but also more divine. The significance of this art experience is not in any way diminished by the fact that an open display of emotions is a rare occasion in the somewhat restrained and stiff art milieu. The unmediated directness of Ance Eikena and her choice of narrative pave the path to a revival of socially relevant themes in Latvian art.

Our Heavenly Father. Exhibition view at the Brīvība Art Space, 2021/2022. Photo: Kristīne Madjare

You have previously touched upon a range of social subject matters in your art. What prompted you to make the ‘Our Heavenly Father’ exhibition right now, at this particular point in time?

My first painting of Dad dates back six years; for the last three years I have known very clearly that my first solo exhibition is going to be ‘Our Heavenly Father’. I have been working on the show throughout this time, both in my mind and in practice, although I did not know where and when exactly it would take place. I just knew that I would have to do it at some point. It grew and changed with me. And then, late last summer, the artist Katrīna Neiburga offered a chance to mount an exhibition in the winter, in the most fantastic space I could have ever wished for this story. I suspect that the exhibition would not have happened for several years had it not been for this opportunity, but now it was clear to me that postponing it any longer was not an option: the time for it to get born was now.

I did feel somewhat confused and did not quite understand why it had to happen at this particular moment in terms of the cosmic order of things: this was a time in my life when I was not dreaming about professional matters at all. And yet ultimately it was exactly for this reason that I felt so free to make this exhibition as a love letter to Dad, God and the young Ance who dreamt about becoming a great artist as a child. I mean, in this very honest and genuine way.

The title of the show, ‘Our Heavenly Father’, the set-up of the exhibition featuring something reminiscent of small altars, and the texts all invoke thoughts of divine worship. It contrasts with the socially accepted way of discussing alcoholism as something weighty and tragic. How did you arrive at this approach to the subject matter?

A couple of years ago, during a truly sad time of my life, I was passing by a church on a Saturday morning and bumped into somebody I knew. I don’t quite remember what exactly was said; I think it was about my insecurity, my being afraid to enter the church because of feeling too much of an outsider. And he told me that it was the sinners, the poor and the lost souls that God held the most dear. I have this card with a text written by the former pastor, theologian Juris Rubenis: ‘I am God’s favourite child even when I’m not His best-behaved child.’ So this is one of the most beautiful ideas I have ever heard: a love that is so infinite and accepting that it embraces you tighter when you are having a hard time instead of rejecting. Sadly, people experiencing hardships are so much more often neglected, abandoned, pushed away. That is why this idea is so hard to grasp. And that is why the question even arises of how you can link something as hard and heavy with God.

I think that alcoholism is first and foremost caused by a shortage of love. Sometimes it is the love you were never given as a child, resulting in a feeling of emptiness in your chest and a shell that keeps you from accepting the love of your fellow humans as an adult. This well of sorrow and loneliness is so deep and so bottomless that the person simply cannot deal with it. Alcohol may create a short-term illusion of filling this void, but the truth is, the only thing we all need is feeling accepted, understood and wanted. Feeling a healing kindness. It’s the same with children who throw tantrums and are disobedient – they need more cuddles instead of punishment. And the sad dads who drink also need to feel more love. That was the starting point for this exhibition all those years ago – the thought that, well, here is my dad who drinks, often lets me down and hurts me, but I understand him, I feel sorry for him, and I love him very much. It’s seeing the hurting yet loving heart hidden behind the countless walls. Forgiving and accepting the other person when it is a very hard thing to do.

Could you tell us in a few words about your creative process – how do you arrive at a specific subject and how do you choose the right medium for it? Which comes first?

Since my high school years, ideas usually have been arriving ready to me, almost as if there was a kind of AI algorithm inserted in my mind that would generate artworks on demand.

I enter a request and after a relatively short time a specific vision, complete with form and content, is produced. I proceed to analyse it and search for solutions, but the fundamental idea usually stays the same it was in the beginning.

It is important that the subject is close and familiar to me, otherwise the result cannot be a genuine and honest piece. I don’t like inauthentic and contrived things. Which is why I never stop questioning every detail during the process of making, to make sure there is nothing superficial and unjustified about it.

I normally find it important that there is a kind of greater cause behind the piece, otherwise it would be like littering the world with superfluous stuff. On the other hand, if your heart desires to paint flowers, you really must do it because you must save yourself before you attempt saving the world.

Your works tend to be very personal and frequently cross the line between personal life and art. Are there any subjects that are off-limits for you?

I don’t think there are. At least I cannot name any right now, off the top of my head. The only thing I try to keep in mind at all times is respecting other people. For instance, I did not use Dad’s most sorrowful letters, no matter how well they fitted the theme.

You have worked in a variety of media. Is there a single one where you feel you are able to express yourself with the greatest ease?

It changes with every work. Of course, sculpture is and will remain my realm. I feel it with my soul and with my whole body. I was recently carving a plaster mould, which I hadn’t done for a long time, and it was like being sixteen again, when I did that for the very first time. It was an incredible feeling, like encountering your most genuine self.

For quite some time now I have been fascinated by your playful ways of working with text. You once said in an interview that you were a human first, then – a tractor driver and last – a sculptor. Meanwhile, in your ‘Heavenly Father’ exhibition, text becomes one of the key elements. How deliberate is the role that text plays in your art?

Text was important in the exhibition because it simply is a way of saying something very honestly and from the bottom of my heart. We all see the world differently, and not everyone possesses this highly developed ability to read a story from images and objects.

Language is a way to come one step closer and speak more intelligibly. And I do want to be closer to the viewer.

Unlike other Latvian artists of the younger generation, you are one of the few who include immediate references to various acute social problems in your works. What prompts you to do that and why do you think other artists avoid these subjects?

It’s simply that these social problems are part of my own life, issues that feel painful at certain moments or things that seem unfair and make me want to address this injustice. For instance, the inaccessibility of the urban environment is a story that wouldn’t perhaps preoccupy me so much if my mum did not have mobility problems, which means that I have a deeper insight and understanding of this issue. Not to mention personal concern and pain. Creating a work of art on the subject is my chance of initiating a significant conversation by doing as much as I currently can. I would like to start helping people directly at some point. But I have a lot to learn before I can do that.

Regarding other people, it is hard to tell; we should ask each of them personally. Yes, there are people who seem to have more money, self-confidence or status, and it’s easy to presume that they simply do not have these problems. But that’s just the external shell that we see, and it is very likely that not everybody is interested in dealing with these matters in their art, as simple as that. Or they may prefer to keep it separate, as their personal life. The closer to home the subject is, the greater the self-exposure and opening of old wounds. Perhaps we could speak about a desire to avoid unpleasant things by the public in general, but I don’t want to make it sound like a reproach. I think it is wonderful that every artist has his or her own niche and, at the same time, an infinite field of potentialities. Different art for immensely different worlds.

What effect would you like your works to have on the viewer?

I don’t give it much thought, not particularly; I find it normal and wonderful that the elicited feelings can vary so much. Even if the viewer does not feel anything at all, that’s also normal. Of course, I do always have a hope deep in my heart that it will strike a chord with someone, at least. During the run of ‘Our Heavenly Father’, a girl who is very dear to me but whom I haven’t seen in a long time, wrote to tell me that she had visited the show and it had made her cry a lot and prompted her to call her dad, which she didn’t normally do. Her dad had been very happy about it, and so had she. And that made me cry. That’s all you can ask of art. In this sense, my faith in the power of art was reborn in me with this exhibition. And a former fellow student tearfully told me the same thing at the opening of the show. That’s an emotional equivalent of the nomination for Purvītis Prize.

I would also very much want people not to be afraid to look for their own interpretation. If you don’t assure everybody that there are no wrong answers, that they are all correct, many people tend to think they do not understand art. But is there ever a single thing to be understood? It is the most fantastic experience when I can tell a viewer what I was thinking when I was making the piece and then listen to their version of the story. The viewer listens to what the artist has to say, and the artist accepts the viewer with an open heart, in a friendly and calm conversation. The two worlds expand at this moment, mine and theirs. And I also sometimes read my own work in a number of different ways.

What are your future aspirations?

I want to be healthy, happy and strong. I am glad and grateful to be invited and given opportunities to take part in various projects. If things go right, this could be a flourishing spring. I very much rely on and surrender myself to the flow of life. I dream a lot about a well-paid office work with all the social security that comes with it. I haven’t abandoned thoughts of becoming a farmer. Just living and following my mind and my heart – all of that belongs to the process of creative research. In a sense, that’s quite cool: whatever I do, that’s always developing new works. I very much hope that the tulips I planted in the autumn will sprout. And there will be a time in the coming years when I can organize huge potato-digging bees. Life in itself is the most wonderful work of art.

The conversation took place on February 2022.

Title image: Ance Eikena. Photo: Roberts Svizenecs