Kristaps Epners’ Maslova

A conversation with Kristaps Epners / shortlisted for the Purvītis Prize 2023

‘Kristaps Epners’ work is based on extended research into the Old Believers’ community in Maslova, Latgale region. We found admirable the artist’s ability to find access to this closed and forgotten community that exists somewhere far removed from our eyes. The end result could be described as a video poem that manages to capture a sense of otherworldliness where the sacred legacy and the person who holds it sacred are of equal value. A church surrounded by woods, also serving as a shelter for grain from the winter frosts and the autumn damp, becomes a sacred island of refuge from centuries-long persecution and prejudice and a road to a personal faith. The artist’s respectful approach to this complex subject that resonates so strongly and bitterly with the current world events,’ – these considerations were cited as the basis for the 2023 Purvītis Prize nomination by the panel of independent experts.

Kristaps Epners’ ‘Maslova’ video installation was shown at the former Riga Stock Exchange building as part of the Survival Kit 13 Festival (03.09.–16.10.2022). The work is centred around Maslova prayer house abandoned by the congregation three decades ago. There are no icons left in the building, only paper flowers and prayer cushions remain, and yet the spiritually charged ambience accumulated over the centuries still lingers. Through a detailed focused observation where every little thing plays a certain role, the artist invites the viewer into the world of Old Believer faith: a wheat grain symbolises resurrection but the chant echoes resistance to oppression and authoritarianism.

Kristaps Epners, a multimedia artist, mostly works in video, installation art and photography. He has studied at the Visual Communications Department of the Art Academy of Latvia. Since 1996, the artist has mounted several solo exhibitions: at the Tartu Art House, the Noass Floating Art Centre in Riga, Kim? Contemporary Art Centre in Riga. Epners also took part in the Diversity United group show at the Tempelhof Airport in Berlin and the New Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, in group exhibitions at the Latvian National Museum of Art, (AV17) Gallery in Vilnius, Tallinn Art Hall, Den Frie Centre for Contemporary Art in Copenhagen, Gdansk Museum of Ethnography, Akureyri Art Museum in Iceland and elsewhere. Kristaps Epners’ works are held in the collections of the Latvian National Museum of Art, Latvian Contemporary Art Museum and Estonian National Museum.

In 2017, Kristaps Epners was nominated for Purvītis Prize for his ‘Exercises’ solo exhibition at the Noass Floating Art Centre and in 2019 – for his multimedia work ‘Forget Me Not’ shown at the Morbergs Residence during the Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art (RIBOCA) in 2018.

Maslova Old Believers’ House of Prayers in 1932 – National Archives of Latvia, Latvian State Archives, Archive Group No. 2633, Description No. 4, File No. 62

You were one of the Latvian artists invited by the curator iLiana Fokianaki to show at the Survival Kit 13 exhibition ‘This Little Bird Must Be Caught’. When and how was the idea of the work born? How did you even end up in Maslova?

[The artist] Jānis Blanks and I used to take part in adventure racing events very often – cycling, walking, boating. And for several years in a row, these races were held in various locations of Latgale. In 2014, there was a race in the vicinity of Krāslava. We were running past an abandoned Latgalian homestead: I turn my head and see a neglected overgrown yard. There was no time to stop and take a proper look, but something about it was calling out to me. Two years from the image that stayed stuck in my mind I was working on a piece for the ‘Contemporary Landscape’ show of Cēsis Art Festival. I was interested in the landscapes that open from the windows of abandoned buildings. I had explored several half-abandoned half-forgotten villages in Latgale, and one of the seven locations that were represented in the work was Maslova.

I would enter the empty buildings, and I must say that they all were different: some were swept clean, and you could tell that the residents had left it in a controlled way; others seemed to have been abandoned unexpectedly – perhaps the owner, an old lady, had been rushed away in an ambulance or something: the table had been laid, there was even tea in the cup. Thieves had combed through every house. If there were any belongings left behind, they had been rummaged through in search for ‘treasures’. In one of the houses I found a hundred-year-old folder containing original documents – a hundred years of the Latvian history. It starts in the aftermath of the First World War: it’s the 1920s; somebody has just been assigned a plot of land. They get some money from the Bank of the new-founded Latvian state to build a house. Then they are granted a credit for building a cattle-shed. Then it becomes clear from the receipts or letters that there have been some difficulties with payments; there are threats to take the property away from them. Then come Russian papers, then – German papers, war time papers that show how much milk or meat they must give away. Then come the post-war years and then, like a cherry on a cake, a daughter or a granddaughter has sent a picture from Saint Mark’s Square in Venice. It seemed so surreal in the context of the abandoned house. All of this has come together, condensed into a single folder.

What struck a chord with me in Maslova and what I cannot explain rationally (nor do I wish to) was the space: it was empty yet at the same time charged. I sensed this ephemeral energy in there. A house of prayers in the middle of nowhere. Apparently, unwanted by anyone: everything has come to an end; the congregation ceased to exist back in 1993. Neither myself nor my family have any connections in Latgale. It is inexplicable to me that I ever stumbled upon this place. Latgale had always seemed like a very distant place, but I don’t see it like that anymore. The truth is, it is not the distance that seems insurmountable but rather the mental detachment. I have had conversations about what Latgale is, and I agree that there is a sense of genuineness in Latgale. Unless they are inveterate drunks, these people are very strong. I think they are the strongest people in Latvia.

Kristaps Epners. Maslova. Work as part of the Survival Kit 13 festival (03.09.–16.10.2022.). Exhibition views. Photos: Ēriks Božis

How long did you work on the project? Could you tell us more about the actual process of creating the work?

It was for ages, but then again, taking my time is typical of me. But it’s not like the process was extremely intense throughout. I had developed a semi-finished version, without a specific exhibition in mind. It was an audio and video recording of the chant, like a study for a finished work. At the time when I met with the Survival Kit curator iLiana Fokianaki, she had already decided that the exhibition would deal with sound, freedom of speech and various forms of protest. I showed her a fragment, and iLiana said that it was a perfect match with her idea and asked me to complete the work.

It was already when I was preparing the work for the show that I arrived at the idea of filming Maslova while walking in circle around the church and knew that the prayer should dominate the whole piece. That’s the way it frequently happens for me: some kind of ‘message’ seems to appear as if randomly while I am working. I must say I generally believe that, if you think about something in an intense way for a long stretch of time, it really does approach you on a level of coincidence or serendipity. It happened to me with the project about Miervaldis Kalniņš [‘Forget Me Not’]. I was working on it; I had already got hold of the original Siberian footage, 8-mm and 16-mm films – a wealth of wonderful material, but how do I put it all together? And then one day somebody asked me for something from Dad’s archive; I picked up a box, spilled the content, and a sheaf of letters landed in my hands; I saw a signature – ‘Miervaldis’. I looked and I found more and more. First, the text was wonderful on its own; second, it provided the work with a solid structure.

Sometimes you can think about things rationally and yet be unable to arrive at anything. It never works this way when you have to get something done really quickly. But during a lengthy process, I believe, things do come together and click, condense or materialise.

“Maslova”, 2022. Film still

Is the prayer house really used as storage for grain?

No, I brought them over for the purposes of filming. The story about the reasons why the cornfield and the grain should feature in the video work unfolded gradually. When I first went to Maslova, I saw empty shells of grain everywhere in the building – not just on the floor but also as high as the shelves for the icons.

A hundred metres from the prayer house lived two hard-working farmers, mother and daughter with their couple dozens of dairy cows. As we got to know each other better, the younger woman revealed that they had previously grown their own wheat, and sometimes, saving the crop from pouring rain, they used to spread the grain intended for the cattle on the floorboards of the abandoned Old Believers’ prayer house to dry. Mice and little birds then scattered some on the icon shelves as well.

It immediately struck me that it was a very special combination – this energetically loaded space and the grain. It was only later that I learnt that Old Believers had this tradition at their funeral feasts of pouring hot honey over live wheat grain and eating. Then the whole thing clicked in place. The greatest surprise was this aspect of the Old Believers’ tradition; the live wheat grain signifies resurrection for them: like a grain does not die in the soil but grows and bears fruit, so will the dead who have lived their lives in keeping with the commandments of their faith resurrect and live in eternity. The funeral ritual is an extremely important part of the Old Believers’ tradition – the wake when women stay up and chant all day and all night.

The third aspect, of course, was the political context: the war where the grain becomes a global political weapon in the aggression toward Ukraine and blackmail of the whole civilised world perpetrated by Russia.

To what extent did you delve into the differences between the Old Believers and the Eastern Orthodox Church?

While I was working on the Maslova project, I spent a lot of time in the archive – examining documents and maps, searching for photographs. Judging from documents dating from the 1920s and 1930s, from various reports, Maslova used to be a centre of faith: practicing Old Believers of quite a few surrounding locations came to Maslova. According to a 1927 report, the congregation comprised residents of 26 villages, 1 hamlet, 8 scattered settlements, 2 properties and 1 manor with 260 families and 1217 souls; however, none of the parishioners remembered the exact time of its beginnings. It literally says that: ‘Apparently dating from the olden times.’

In mid-17th century a church reform took place in Russia. It was centred around the idea of the Third Rome, born some time before the reform, back in the 16th century. As in: people of Orthodox faith, unite to preserve undistorted Christian faith! Moscow is destined to become the Third Rome, following the original Rome and Constantinople, both of which ‘fell’. That was a political decision by Tsar Alexei Romanov, and I can feel power and imperial thinking go hand in hand here.

The first of the Romanov Dynasty tsars, Alexei I, also known as The Quietest, ascended the throne at the age of 16 and was known for forging economic ties with Europe. Inspired by an influential priest from Jerusalem, the Tsar agreed to proceed with the church reform proposed by his favourite, Patriarch Nikon. Without considering the differences of opinion among the highest clergy, the reform was carried out by force: this is how it’s going to be from now on. As a result, the reform incorporated a strong Greek influence (disregarding the fact that the actual Greek tradition, the original source of Christianity in Russia, had evolved significantly, to some extent due to the influence of the Catholic Church), both regarding the ritual and changes made to the texts and spelling of certain words. For example, the name of Jesus – Ісусъ – was changed to Іисусъ. Similarly, the sign of the cross was now made with three fingers instead of two; the direction of processions around the church was changed to counterclockwise. Other things that a religious person may find essential were changed, too.

A very large part of believers did not accept the reform, and the ‘proper’ Orthodox Church, the one that enjoyed support from the Tsar, started to refer to them as ‘raskolniki’ – schismatics; Old Believers as a term was only introduced in official documents in 1905. There were harsh repressions against the opponents of the reform. Spiritual leaders were tortured and later killed; public trials were held. In the early stages of the persecution there were some cases when whole families, along with their children, self-immolated, so that, purified by fire, they could end up in Heaven instead of the hand of their persecutors. The Old Believers fled to places they deemed harder to reach for the authorities, to the outskirts of the Russian Empire – coast of the White Sea, Karelia, Siberia and even beyond the Russian borders, including Rzeczpospolita, specifically the region that is part of Latgale in today’s Latvia. They felt safer there.

The territory of Latvia was left empty at the time. After all the wars and diseases, the local landowners were happy to see people arrive – people who wanted to work the land, people who did not drink. The Old Believers lived in their own communities, their own villages; they built their houses of prayer. Houses of prayer could only look like living houses and could not feature architectural elements characteristic of churches (for instance, stand out with their bell towers). Compared with other houses of prayer, Maslova is quite an opulent one, with decorative elements on the façade, papered walls and a bell tower – although three sections of rail hang in the tower instead of actual bells (Old Believers frequently used pieces of rail to call people to the service, replacing the forbidden bells).

The laws relaxed with time, although the bureaucratic process of obtaining all the permits was quite hard; in 1905, the Tsar issued a manifesto of religious tolerance. And with the foundation of the Latvian state, Old Believers became equal members of the society and enjoyed the same rights as any other religious denomination.

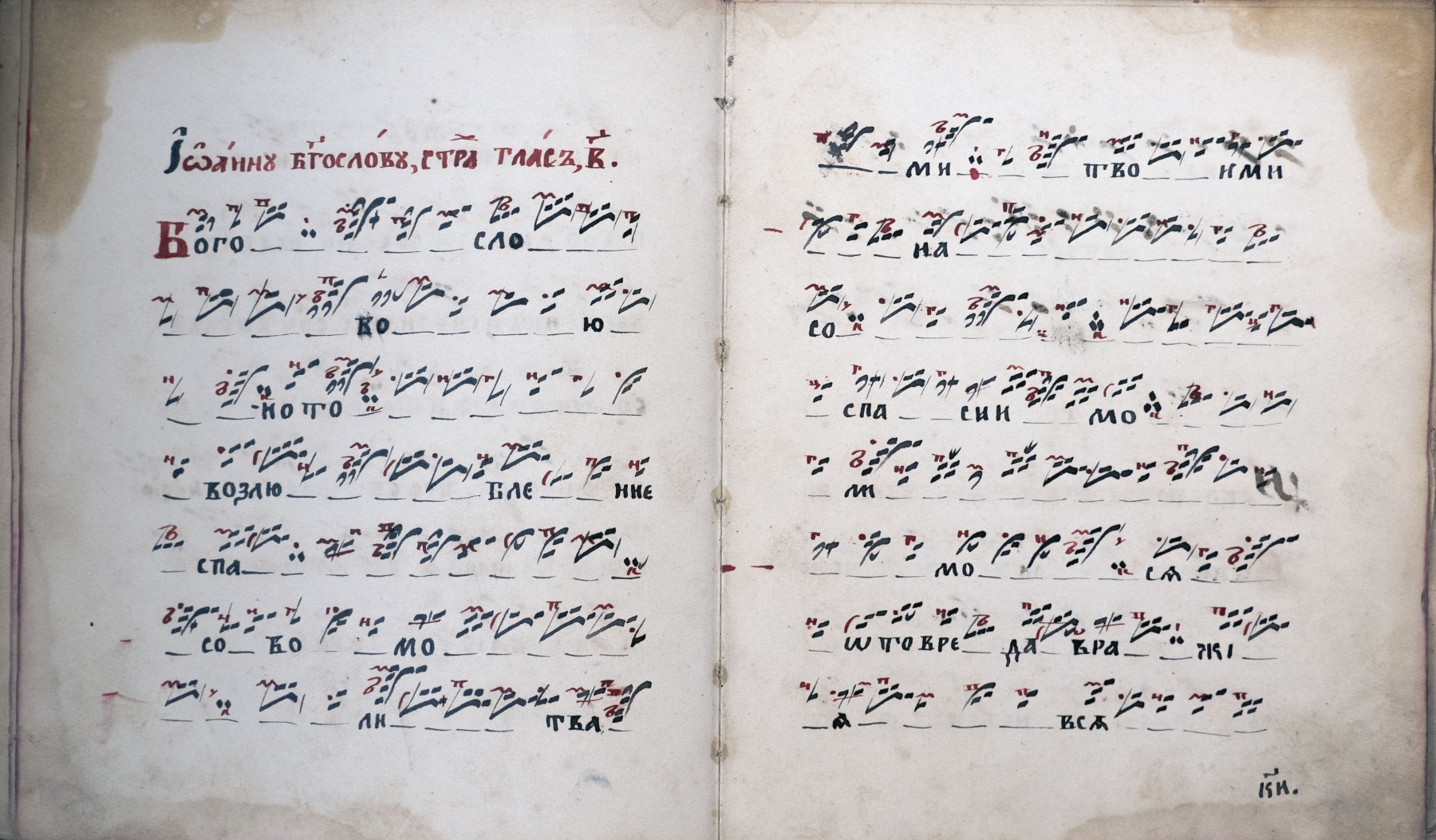

Hymn book belonging to the Timofeyevs family. Film still

One of the changes introduced by the reform had to do with singing.

Yes, the Old Believers’ tradition does not accept the polyphonic chant. That is why I asked the protagonist of my film, Varvara Dorofeyeva, an Old Believer from Dagda, which is not far from Maslova, to sing for me, because apparently one of the numerous prohibitions brought by the church reform was banning Old Believers from carrying on their tradition of singing in unison. Initially only men were allowed to sing at the service but it seems that it is not considered as important today.

The European system of musical notation was standardised over centuries; today we use notes to transcribe music. The Old Believers’ chants, which are always prayers, are never transcribed with notes: the system came to Russia later. Besides, it came from ‘the West’ and was therefore to some extent associated by the Old Believers with the secular, temporal world. The Old Believers use a very specific system of transcription: the chants are performed following ancient symbols of notation that are visually reminiscent of flags of hooks; they call it Znamenny Chant (‘sign chant’) or Kryukovoy Chant (‘hook chant’). The text is written down in Old East Slavic, a language used exclusively in the church (at church services, in the liturgical texts). The way these chants are sung is determined by the hooks – not the pitch but the correct spiritual, emotional and logical way of singing in accordance with the musical correspondence: each sign is a movement of the soul. To me personally this very specific musical system was a revelation; it was something I had never encountered before.

[The publicist, art and sacred heritage expert] Elvita Ruka is promoting inclusion of this unique chant tradition of Old Believers in the territory of Latvia into the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage. (It has already been included in the Latvian National Intangible Cultural Heritage list.)

Due to the fact that Old Believers historically scattered in every direction and ended up settling down very different territories, the communities lived their separate lives, interacting with the local environment, and each acquired various unique features, including some related to their understanding of the singing tradition. Old Believers in Latvia sing their chants very differently from Old Believers in Romania or Siberia. On a theoretical, ‘advanced’ level, only a handful of people know Znamenny Chant in Latvia; these so-called Regents can read, understand, sing and teach others all the signs. There are a couple hundred people who carry on the tradition and can sing from memory and experience – on the ‘oral level’, so to speak – like Varvara from Dagda.

Maslova Old Believers’ House of Prayers in 1978 – Information Centre for Cultural Heritage of the National Cultural Heritage

Administration, the Photo Negative Collection, inventory No. 28759 and 28769.

You said that you spent a lot of time at the archive. What kind of photographs were you trying to locate?

It often happens that I spend days and days rummaging through archives but ultimately there is nothing to show visually from the research in the end result. I went to the archives with one thing in mind: I wanted to find an old photograph of Maslova, dating back as far as possible, that would show some kind of life around the prayer house. The oldest one I ever found was from 1932, without any visible activity going on, but it was visual evidence of what the building looked like immediately after the capital renovation on the money allocated to the Maslova congregation by the Latvian government. The photo was shown at the exhibition.

During the interwar period there were nearly a hundred Old Believer congregations in Latvia. Each of the congregations received annual allowance from the state but in special cases, when a renovation of a prayer house was required, they were given larger funds. And Old Believers were mostly true patriots of Latvia. The leaders elected by the congregations had to confirm their loyalty with an oath of allegiance. The Old Believers felt grateful for the freedom of faith they could enjoy. The historical experience of life in Latvia while it was still part of the Tsarist Russia was also relatively less traumatic. As for the attitudes in today’s Latvia, I could not say either way. The minds of so many people, and not just in Latgale, have been befuddled so badly.

I also visited the State Inspection for Protection of Cultural Monuments in my search for photographs of Maslova. I found materials from field trips in 1978, 1985 and 1995: a visiting expert from Moscow had toured the extant prayer houses and compiled a registry of icons. Maslova was full of icons back then. The photographs on view at the exhibition were from the materials of these field trips.

Thanks to the 1927 report on the Maslova congregation that I found in the State Historical Archive, listing placenames of locations populated by Old Believers, I was able to transfer this information to the map and get a visual idea of the territory around the spiritual centre that was the Maslova prayer house. Following the directions on the map, I started visiting the houses one by one. On one of these trips I met a man who said he was Catholic but told me about his classmate back at Vecokra school, a descendant from a famous family of Maslova Old Believers. The surname of his classmate, Timofeyev, was familiar to me: I had memorised the names of generations of spiritual leaders of the Maslova congregation during my time at the archive. It turned out that he lived less than 15 kilometres from the place. I called him and was on my way. As I was approaching his house, the road started to feel suspicious: the surfacing was solid but quite obviously had not been used by cars for some time. I passed an abandoned house, then another one, crossed a little river and found myself in the yard of a small homestead surrounded by woodlands, with a view of almost the Garden of Eden. The owner, a chatty man, confirmed my suspicion that several of his ancestors had served as spiritual leaders in Maslova.

I asked him for pictures, but he did not have any. ‘And incidentally, Kristaps, what’s the difference between the Orthodox Church and Old Believers?’ he asked me. And that’s a man whose grandfather used to be chair of board at Maslova congregation, an icon painter and scribe who copied Old Believers’ manuscripts.

My search did not end on that. Next, I met up with this man’s cousin Zoya in Jugla, Riga; she had no photographs, either, because her mother, a very religious woman, had burnt them all before death. Zoya gave me the contact details of another relative, but the woman also did not have any pictures of Maslova. What she did have was manuscripts copied by hand by their mutual grandfather from the Maslova congregation. I included a frame with a spread of a hymn book belonging to the Timofeyevs in the film.

I never found the photograph that I had in mind.

“Maslova”, 2022. Film still

Did you get to have a proper conversation with Varvara Dorofeyeva? How did she react to your interest in Maslova?

I ended up contacting Varvara because I needed a living Old Believer. It turns out that she comes from a large family of Old Believers. She grew up in the village of Sotnikova, not far from Maslova, and her grandfather had built a house of prayers for the Sotnikova congregation in 1927 with his own hands. In 1964, the head of the local kolkhoz used deceit to wipe the prayer house off the face of the earth. They moved their icons from the Sotnikova prayer house to Maslova, but when the Maslova congregation disbanded – to the new house of prayer in Dagda, where Varvara is the principal figure now. Varvara used to attend the Maslova prayer house frequently, up to the moment it was closed down – as a child, driving in a horse-drawn cart with her grandmother to visit the cemetery where her ancestors are buried, and later, visiting her mother, who lived nearby. This is her place.

Varvara belongs to a different world. She never gets angry, because anger is a sin. Although Varvara is very forthcoming and open, which is untypical of Old Believers, I can never tell what she really thinks.

The architect, researcher of sacred heritage and lecturer Ludmila Kleshnina told me that Old Believers in Latvia are much more open than their brethren in Russia, because they have been living in a much more welcoming environment for centuries, and their attitude toward non-believers is different. In Russia, if you visit an Old Believer’s home, they will offer you a drink from a cup that is meant for strangers only. They are very hard to get through to. The centuries of suffering endured by Old Believers’ in Russia have left an indelible mark. I can’t say the same about Varvara, although at some point she did say to me: ‘Ой, Кристапс, не знаю…’ (Oh Kristaps, I’m really not sure about this…)

I got a taste of the Old Believers’ different attitude toward the rest of the world – ‘leave us alone’ – when, shortly before the main filming day an orthodoxically inclined Old Believer from Riga turned up unexpectedly in the yard of Varvara’s house in Dagda: a young man, with glazed-over eyes, clutching a tablet and unmistakably already worked up. My experience from previous contacts with Old Believers had been very pleasant until then, but he started interrogating me about my exact plans and intentions. He said he had seen a Hungarian film [‘Natural Light’, 2021, director Dénes Nagy] featuring footage shot in Maslova. The prayer house was now defiled because there had been a half-naked woman in the footage. And he is saying all this addressing Varvara, but I have shooting to do in two days: I have made arrangements for a load of grain to be delivered, I have booked the camera operator Valdis Celmiņš… (I shot most of the material for the film but asked Valdis to film the key footage where the camera circles the prayer house.)

Varvara is an Honorary Citizen of Dagda; she is the one keeping together the Old Believers’ community there. I personally went to Dagda and brought her to see the exhibition in Riga; her daughter and granddaughter, who live in Riga, were also present. Varvara was in tears. But she belongs to one world, and her daughter and granddaughter – a completely different one.

“Maslova”, 2022. Film still

Then you are not the only one who has immortalised Maslova in a work of art?

The Latvian film studio Mistrus Media made a co-production with Hungarian filmmakers. They used the Latgalian landscape in the film, including Maslova house of prayers.

We were spending some time in Berlin, and I used to call the Maslova neighbours every now and then. And one day the ladies tell me that the yard had been full of cars the day before: somebody is shooting a film. I was immediately aware of the potential danger, knowing how cynically film crews can treat the environment they use as a set, and contacted the art department of the Latvian side. It turned out that the story demanded an impression of total poverty, and to create that, they were planning to remove the wallpaper from the walls of the prayer house, promising to replace it once finished. But I needed Maslova the way it was – untouched, up to the last little empty wheat grain in the corner of the room!

On the one hand, Maslova is unclaimed property: there is no-one to ask for permission to do things. On the other hand – how can you do that?! It is not a tumbledown abandoned private house, after all.

I turned to the State Inspection for Protection of Cultural Monuments for advice. Since Maslova is not listed as a cultural landmark, I was advised to submit a petition to the Inspection, which I did. But these decisions are never made overnight, whereas filming was scheduled in a week. Although I had been promised by Mistrus Media that they would not touch the wallpaper after all, I still contacted the local cultural landmark inspector in Krāslava and asked her to drive over and keep an eye on the place. She had indeed done that and kept the wallpaper safe, strictly forbidding anyone to touch it.

Despite the fact that the Inspection eventually decided to support listing the prayer house as a regional architectural landmark, Maslova has not been granted this status; the land is owned by the local government but the building – by a congregation that does not exist anymore. The Andrupene Parish does not want to assume this responsibility: it would mean that they have to take care of the building, which they are not willing to do due to shortage of funds. So the reality is that the prayer house is no more protected than it was before. It is only thanks to the fact that there is a dairy farm next door with two hard-working women and a couple dozen cows that the prayer house has not been turned into a dump of rubbish or burnt down during all these years.

In the name of a balanced account of events I must now return to my Orthodox Old Believer. We spoke, and he admitted that the idea of all the restrictions imposed by the status of a cultural monument makes him mad, because he, too, is planning to take down the wallpaper in Maslova. Truly, we all look at the world through different eyes.

“Maslova”, 2022. Film still

Do you know why the congregation stopped existing?

The countryside is changing; everything is becoming different as a result of globalisation. It is not unexpected, there is no novelty about it: these cycles of transformation are natural. Maslova is no exception to that rule. People leave the countryside, people die, people stop believing in God. How many truly religious and actively practicing people there are in Latvia? Dagda is a dozen or so kilometres from Maslova; they practice the Old Believer faith there; there is a small congregation there.

A stone’s throw from Maslova, there is Lake Okra. It is not a large lake: a bird’s flight distance from the opposite bank to the house of prayers is two kilometres. From the archive materials I know where to find Old Believers’ homes.

On a Friday night, I drive to one of these houses on the opposite bank from the house of prayer. There is a family sitting around the table in the yard, enjoying a drink. I tell them what I am searching for. The host invites me in and shows framed photographs of the family on the wall. It turns out that his mother, an Old Believer, is also present in the yard – an elegant lady sporting a bob haircut. Apparently, she used to cross the lake in a boat and attend the house of prayers. Not anymore. Again – all the pictures, apart from the ones on the wall, have been burnt! We talk, and at some point the lady tells me that Maslova does not exist anymore. ‘What do you mean – does not exist?! I spent last night in a tent right next to the building,’ I say. I show her pictures on my phone but it’s no use. The day before, she went to tend the graves in the cemetery that is located 350 metres from the Maslova house of prayers. The path to the cemetery is a winding one, so you cannot really see the building from there: bushes and trees obscure the view. She was there, and now she tells me that the place is no more. And so the conversation was left open for us.

Had the war in Ukraine already started when you were making the work for the Survival Kit show? What was the impact it had on the process?

Yes, the war started in February 2022, and the shooting was done in the autumn. I also used some things from the 2016 footage.

I told Varvara at once that I am deliberately using the chant in a specific way; it is like a prayer against the horror of war, because war is always a terrible thing. She agreed. I sensed that there was a sensitive line that should not be crossed, so I spoke very carefully; I didn’t say that one side was culpable while the other was not. If you address people in a very categorical way, the doors will close for you. After all, the person does not need you; it is you who needs them. The same goes for the language. Varvara does not understand a single word in Latvian; I had to speak in Russian with her.

The sublime influence of art and culture disappears when confronted by extreme violence. We know examples when it is simply swept away and replaced with brutal force. I believe that respectful treatment of a mind befuddled by propaganda and an art form that does not speak a didactic direct language can help heal a traumatised consciousness.

Where are you at right now as an artist?

I must say that I currently don’t have any inner motivation to start new things. The war has had a huge impact on me. I am renovating my flat, knocking off plastering from walls. It is like therapy for me. Ieva [Epnere] and I had a joint show in Vilnius in 2022 at the AV17 Gallery. It was at the time when the war started. I thought – is there even any point in showing anything? On the other hand, I have to do something. But there is a huge question mark regarding all that for me. In any case, it has made me re-examine all the cultural, artistic and humanitarian ideas.

The whole Survival Kit show was about the relationship between art and sound and the ways they ‘echo’ democracy. Art and music as a declarative gesture of nonviolent resistance or a form of collective performativity. Can art provoke any actual change?

I think what matters is the hope that art can change things. Then comes the brutality of the real war and sweeps it away, all of it. I think iLiana chose my work for the reason that Old Believers as a whole are living evidence that you can survive and hold on to your conviction; what they believe may be erroneous, but it does not matter. Old Believers are very conservative, very much driven by text, by books; they strive to stay unaffected by change, and that is why they strongly believe that they are the genuine ones. That’s what all ideological struggles are about. The German culture – who needs it if the person living in this environment has been zombified? Or the Russian culture? And what about the monuments to Pushkin that are being demolished in Ukraine right now? I think we are witnessing an insane time right now, and the great worry is – what happens if the tension reaches an extreme level? It would be important to have something to come back to once the horror is over. That is when there is a point to culture in the broader sense of the word. If we do not have that, there is no goal, no motivation.

Title image: Kristaps Epners. Photo: Māris Ločmelis