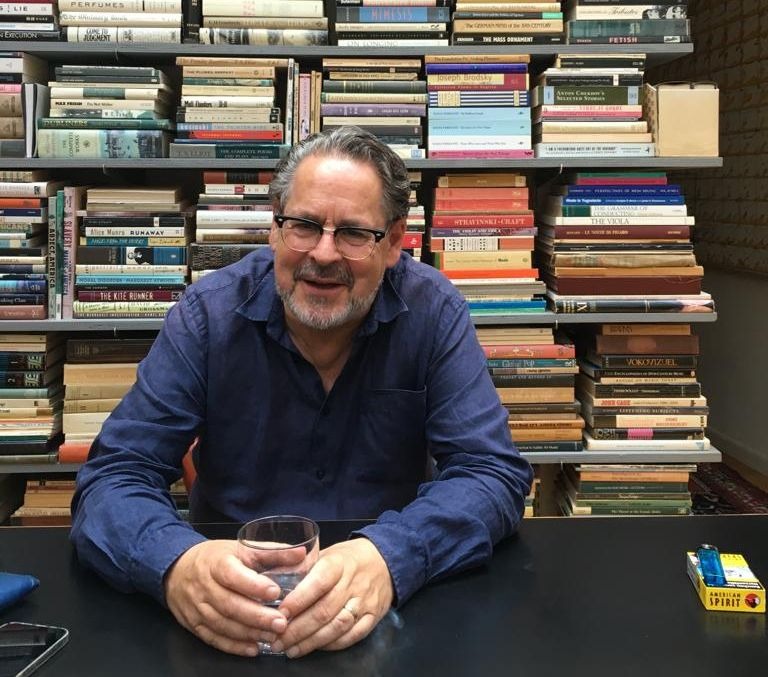

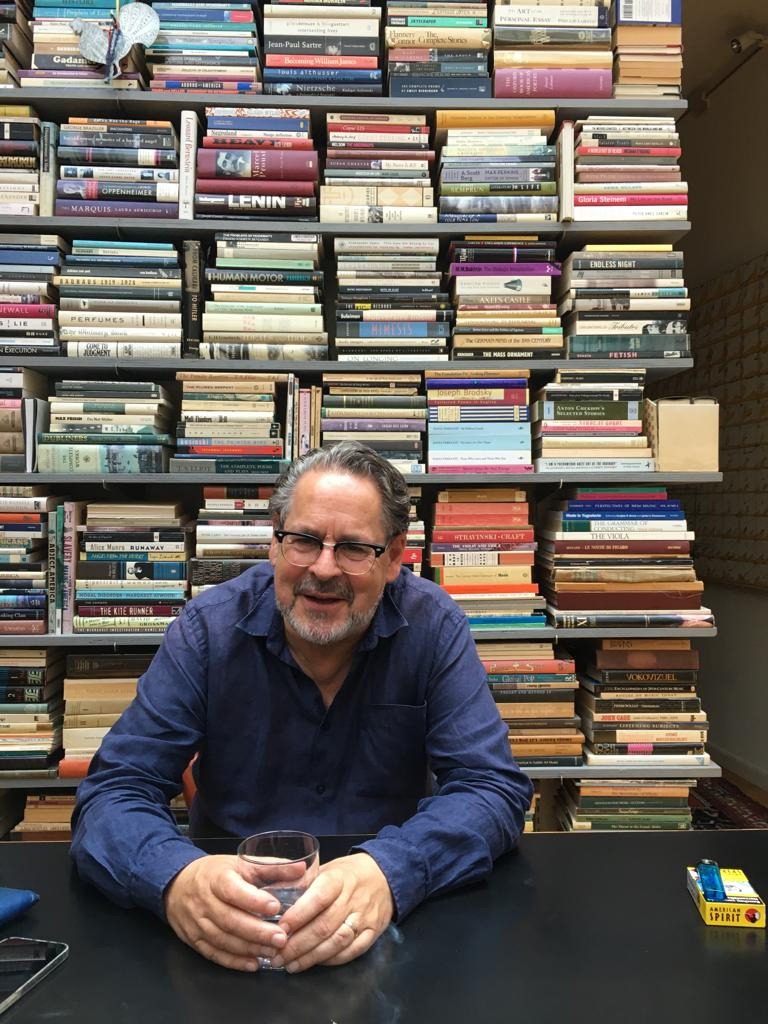

Drawn to challenges

An interview with curator Udo Kittelmann

Udo Kittelmann is one of the most prominent figures on the contemporary art scene. His frequent large-scale exhibition projects include the The King is Dead, Long Live the Queen at the Museum Frieder Burda which opened 12th of May 2023; Human Brains (2022) and The Boat is Leaking. The Captain Lied (2017), both of which were on view at the Fondazione Prada in Venice; and K (2020), which was shown at the Fondazione Prada in Milan) have always evoked admiration for the curator’s ability to think complexly on infinitely many levels, and his ability to whirl and develop an idea, allowing himself to simply flow, guided by curiosity. Questions are asked and answers are sought as he maintains a clear focus and discovers a world in which different phenomena are revealed in layers. For him, the power of art lies in its ability to make people discover. We live in harsh times and in a complex world that is changing at an unimaginable speed. “And when I see what is happening, I want to create something that hopefully responds to this.” Kittelmann is like a conductor under whose guidance the orchestra/exhibiting artists/team strive to create what is known as a Gesamtkunstwerk. And yet, at the end of his twelve-year career as Director of the National Gallery in Berlin, he organized an exhibition in a flower shop showing works by Austrian ceramicist Walter Bosse. “I don’t believe in hierarchies, I never have. [...] I have the privilege to continue my days of playing in a sandbox as a child. Nothing has changed, only the tools.”

The following conversation took place in Riga, where Kittelmann had traveled to as a member of the international jury for the 2023 Purvītis Prize.

Exhibition view of "The King is Dead, Long Live the Queen" - Kerstin Brätsch, Towards an alphabet_Dino runes (Baden-Baden Version) A-K (Detail), 2023. Museum Frieder Burda © Kerstin Brätsch; Julia Scher, Girl Dog (Hybrid), 2005. Courtesy the artist and Esther Schipper, Berlin / Paris / Seoul; Almut Heise, Große Museumsszene, 1989. Leihgabe der Künstlerin © VG Bild-Kunst 2023; Galli, Wer das Gelbe nicht ehrt..., 1981-87, Oft sieht man die Zitrone kaum, 1989, Wer bis drei zählen kann, kann gerettet werden, 1996-99. Courtesy the artist and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin; Foto: Nikolay Kazakov

Please tell us about your latest project currently on view at the Museum Frieder Burda, a dedication to an exhibition organized by Peggy Guggenheim 80 years ago. Just as in the exhibition back then, this show also features artworks by 31 women.

Maybe I should start with how I began to think about this exhibition titled The King is Dead, Long Live the Queen. As we all know – and for very, very good reasons – over the last ten to fifteen years there have been many exhibitions dedicated to women artists – to female artists’ work. But most of them I criticized for one single reason: They were very much a discourse of feminism, women’s power, gender, and lately, queerness, and they did not, in my understanding, consider the artworks that had been chosen – the power of the artworks themselves. And then I read about the exhibition titled 31 Women that Peggy Guggenheim (1898-1979) had organized in 1943 in her gallery at that time, Art of This Century gallery, in New York. Some of the artists in the exhibition are still known today, however, most were unknown – they were mainly the wives, partners or muses of the male artists that were being presented at that time by Peggy Guggenheim. That is one part of the story. But when I read that it was probably Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) who came up with the idea, and that he also helped shape the exhibition, I became quite curious about why 31 artists. This is quite strange; usually, we have 5, 10, 15, 20, and so on and so forth. As you know, Duchamp, at that time, was very passionate about playing chess. And so I created, let’s say, my theory about the number 31. Duchamp was very much interested in numbers. Always. The chess game has 32 figures, 16 on each side, and if you take one out, you cannot play. Or the other way around – who is the weakest figure in chess? It is the king, and the most powerful is the queen. So that is how I came up with the title.

Exhibition view of "The King is Dead, Long Live the Queen" - Patricia Waller, o. T. (Superman), 2011. Courtesy of Galerie Deschler, Berlin © Patricia Waller and VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023; Galli, Wer das Gelbe nicht ehrt..., 1981-87, Oft sieht man die Zitrone kaum, 1989, Wer bis drei zählen kann, kann gerettet werden, 1996-99. Courtesy the artist and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin; Photo: Nikolay Kazakov

Then I started to think about an exhibition with 31 female artists. Without one single theme enveloping the whole show, without covering each work with a shroud of discourse or ideology. In my text, I did not even mention the words “women’s power”, “feminism”, or so on. But the works that I chose are all strong enough that they speak for themselves about issues such as feminism, women’s power, gender, and racism to the average viewer who comes to see the show. I believe very much in the power of the pieces as stand-alone artworks. Increasingly over the last 20–25 years, we’ve been having all these discourses – undoubtedly important – but we should not lose the idea of first letting the artworks speak for themselves. I did the show with incredible female artists and incredible works of art, and so far, it has gone very well. What I asked myself more and more as the opening came closer was – would it have been the same if I had collaborated with 31 male artists? Because the collaboration went brilliantly. It was really a pleasure to work with all the female artists. I guess there is a difference between the egos of men artists and women artists – between how they think about themselves.

First row (From left to right):

Beatriz Morales; Rosa Barba; Sara Nabil; Asta Gröting; Hiba Alansari; Conny Maier; Patricia Waller; Marianna Simnett;

Second row (From left to right):

Julia Scher; Heidi Manthey; Monica Bonvicini; Almut Heise; Leiko Ikemura; Leda Bourgogne; Roey Victoria Heifetz; Karin Sander; Alexandra Bircken; Annette Kelm / exhibition “The King is Dead, Long live the Queen” at the Museum Frieder Burda in Baden-Baden. Photo: Nikolay Kazakov

Could you elaborate on that last point?

All of the women artists that had been invited and then worked together really understood how to collaborate with each other. There was no competition, not at any time – not about what kinds of works I or we chose, nor about where and how a work was installed or hung. It was a great, great experience.

Did this surprise you in some way? Because the way you’re talking about it, it seems that you weren’t expecting this.

First of all, I took this exhibition on also because I wanted to work again with the women artists I had worked with from the late 80s onward. And, of course, I also chose upcoming women artists that I was curious about.

If you work on an exhibition with so many artists, you never know how it will turn out; you never know about the energy; you never know where it will finally lead. It is always a challenge to create an exhibition just with one or two artists! Yet it is nevertheless much easier to organize and think about than an exhibition with 31 artists. It is a kind of little “documentina”, or a little biennial with 31 artists. I really enjoyed it, I have to say.

Is there a difference between art created by a man and art created by a woman?

It is possible, but is not what is relevant. To me, what always counts is the result. I guess the best result would be that one cannot ‘t even tell if an artwork has been created by a woman or a man. It is mainly about that – first of all, we are humans. That’s it.

Exhibition view of “Transformers” at the Museum Frieder Burda / Jordan Wolfson, “Female Figure”, 2014. Animatronic sculpture, sound, 182.9 x 73.7 cm. © courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York, Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photo: Nikolay Kazakov

That is true, we are humans, and that is exactly why we would like to ask you about the exhibition you did at the Fondazione Prada devoted to the human brain. If we look at ourselves, at what we are doing in this life, we always want to find a purely personal purpose for doing something because, in the end, we are the only ones who are experiencing our one and only life. Besides the professional challenge it presented, what was the personal reason for you doing this exhibition? Were there any questions you wanted answered for yourself? Or perhaps you were searching for something? In essence, why did you take on this exhibition?

To begin with, I have always searched for something, and am always drawn to challenges. And when Muccia Prada got in touch with me and asked if I could imagine creating an exhibition about the human brain – about neuroscience – I thought about it for a day or so and answered “yes,” even though I did not yet know how I was going to do it. For a long, long time now I have believed that exhibitions should not be limited to just the subject of art. Historically, that might have been the case, but it no longer holds looking from today’s perspective. I wrote in an essay in the catalog for another exhibition, titled Transformers, that I really believe that the idea of an art museum, as we know it today, will come to an end very soon, and for many good reasons.

But going back to the Venice project – I wanted to challenge myself. There had been a committee, and in the beginning, I was the only one from the art world – all the others were philosophers, doctors and scientists. Wow! They had a totally different idea about how to shape an exhibition on the topic of the neuroscience of the human brain. The majority wanted to illustrate the topic the same way it has already been done in books or on YouTube, TV or more. But I had a totally different idea about how to do it and to attract all types of visitors. Therefore, I invited the artist Taryn Simon, who is for me, one of the most visionary artists of today, to co-create this exhibition with me as it was clear that my vision alone would not be enough. And in the end – luckily, I have to say – we did it. But what a journey it was! And while Simon came up with the Conversation Machine, to hear all the voices simultaneously engage in a conversation about the meaning of the human brain, for sure she created a masterpiece which most certainly will remain as a new way, intellectually and aesthetically of how to engage people to think about something so complex.

Exhibition view of “Transformers” at the Museum Frieder Burda / Foreground: Ryan Gander, “I ... I ... I ...”, 2019. Animatronic sculpture, sound, 19.4 x 24 x 22 cm. Sammlung Harm Müller-Spreer. © The artist/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022. Background: Gerhard Richter, “Candle”, 1982. Oil on canvas, 100 x 100 cm © Gerhard Richter 2022. Photo: Nikolay Kazakov

The body of this exhibition combined art, science, and fictional story. What was your biggest challenge in creating such a complex piece?

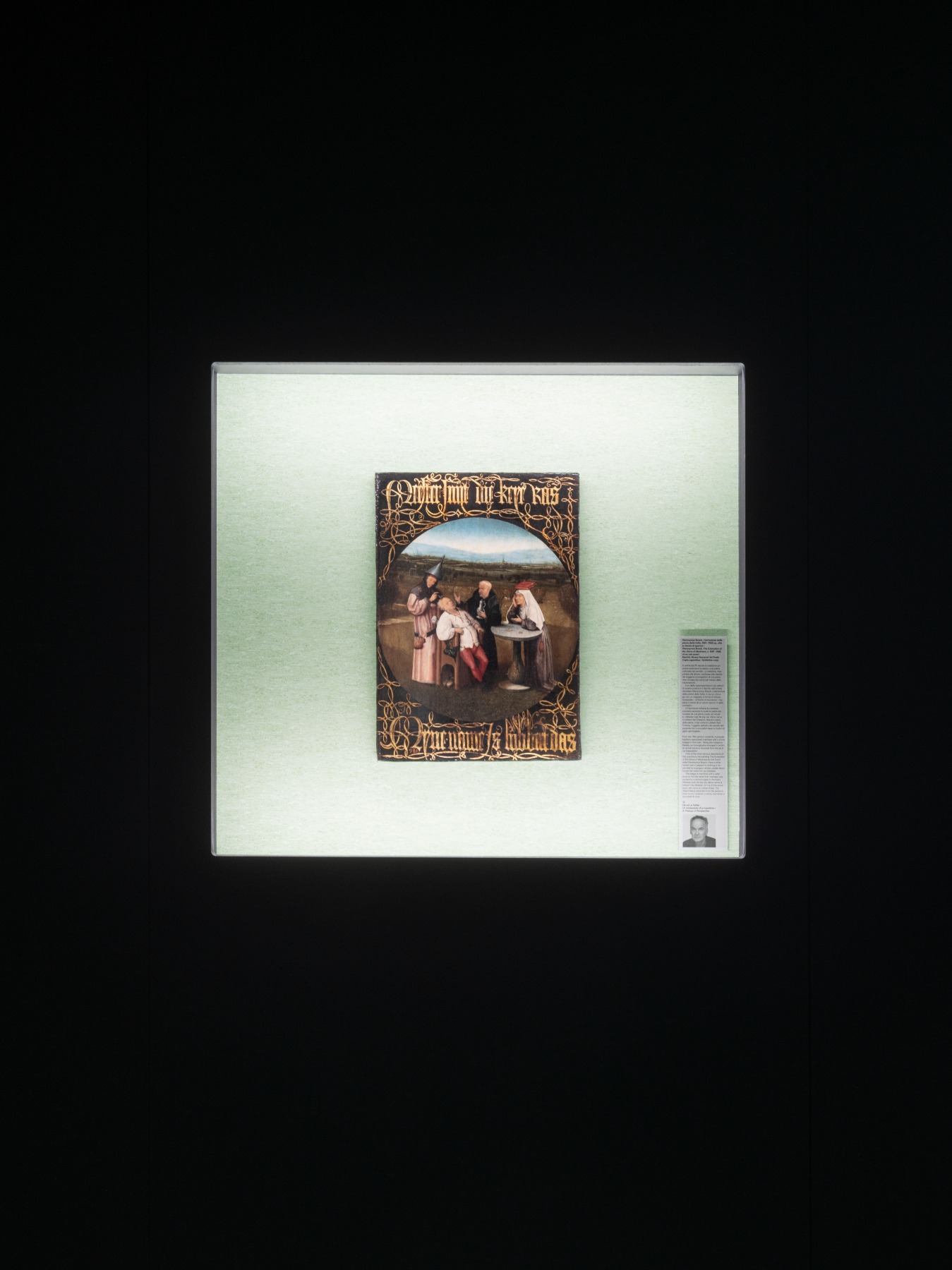

Some of the artifacts that we exhibited as artworks were not originals, but very good facsimiles. In general, I doubt more and more over the last few years that originals need to be presented when it comes to a visual impression. The largest task was to invite many scientists from different disciplines and cultural background to talk about neuroscience and to invite authors and poets to write fictional texts about the artifacts that were exhibited. It was a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk. I also wanted to create a perhaps not new but, let’s say, refreshing idea of a museum. It does not matter whether it was an art museum or a science museum.

Exhibition view of “Transformers” at the Museum Frieder Burda / Louisa Clement. “Representative”, 2022. Robotic TPE body produced using the measurements and appearance of the artist, implanted, artificial intelligence chatbots, programmed using the characteristics and biography of the artist, 169 x 40 x 30 cm. © Louisa Clement / Cassina Projects, Milan. Gerhard Richter, "Party", 1963. Oil, nails, and cord on canvas on newspaper, 150 x 182 cm © Gerhard Richter 2022. Photo: Nikolay Kazakov

It is a formidable hypothesis, but in terms of how such a complex organ as the brain works, it takes all of these impulses – what we see, hear and experience – compiles it and processes it, and then somehow, like an instrument, helps us navigate this world. Connecting this to art, I think there is some similarity because one of the missions of art is to help us – to provoke us to think, to help us steer through this journey we call life.

It is mainly about to provoke a thought. What makes you think? That is what art and poetry are all about.

Precisely.

In a way, that is what I am always searching for. How can you make people think? And to make them think, you have to challenge them. Don’t make it too complicated, but also not too easy. You have to find a balance...

It’s like what the brain is doing all the time – it’s balancing.

Exactly, exactly. This was very much constructed into the architecture and into the pieces we chose to keep, let’s say, one’s mind “fresh”.

In an interview after the exhibition, you said that one of your discoveries in making this exhibition was that the brain is the only organ in our body that we cannot feel.

Exactly. It is totally abstract. You have no idea that your brain is the organ that coordinates and runs everything. I never thought about that before.

It’s a bit shocking.

Yes, exactly. This exhibition, this entire project, brought everyone who participated in it to their limit. It was really a tough job.

Exhibition view of “Human Brains: It Begins with an Idea” Photo: Marco Cappelletti Courtesy: Fondazione Prada The neurophysiology of memory explained by Wilder Penfield, neurosurgeon of McGill University Montréal; footage from the film Gateways to the Mind, 1958

You love being interdisciplinary within your projects. For you, it is essential to combine different mediums and cultural fields – you like to involve literature, music and movies, as well as reference today’s and past cultural icons. How would you describe your curatorial method?

It is the thinking – the power of thinking. It started a long, long time ago. Dealing just with artists and artworks and the art world as we know it was not enough for me. I was curious; I wanted to find out more. Literature enhances imagination. Reading stories allows me to have ideas which I feel always inspired to translate or transform into exhibitions.

My understanding is always to have enough time and space to react quite spontaneously. Because the world is changing at a tremendous speed. And when I see what is happening, I want to create something that hopefully responds to this. Maybe through, for example, artworks, but from time to time I mix all the different mediums together. It does not matter if it comes from a feature film, poetry or other cultural studies.

I’m in a very, very lucky situation as a human being. If I have to explain to somebody who is not familiar with what a curator does, I always say: imagine that I have the privilege to continue my days of playing in a sandbox as a child. Nothing has changed, only the tools. That is it. This is how I see it. Some people would say it is quite naive, but I believe it is very, very important to keep a bit of naivety, to not lose your sense of humor.

Exhibition view of “Human Brains: It Begins with an Idea” at the Fondazione Prada, Venice 23 April – 27 November 2022 / Photo: Marco Cappelletti / Courtesy: Fondazione Prada /

Cylinders of Gudea Iraq, c. 2120 – 2110 BCE, terracotta Musée du Louvre, Département des Antiquités Orientales, Paris Exhibition copy

And also be open to discovering new tools.

Yes, exactly.

You mentioned that the concept of the museum as we see it nowadays will soon end. I remember my conversation with Sam Keller some years ago, before the pandemic. He said his famous words: that for him, the museum is a forum; it’s the last space of true freedom. But you’re saying that you feel that the concept of the museum is over and done with.

What I want very much is a museum that is permanently on the move. I don’t want it to be anymore aesthetic than it is. I want it to be more free, which is quite difficult because we are losing freedoms. It doesn’t matter if you work in a museum or elsewhere, we are losing freedoms. So we have to fight for freedom.

We live in tough times.

Exactly.

Do you believe that not only art but culture in general can help people survive these times?

Absolutely.

Exhibition view of “Human Brains: It Begins with an Idea” at the Fondazione Prada, Venice / 23 April – 27 November 2022 / Photo: Marco Cappelletti / Courtesy: Fondazione Prada / The Conversation Machine

Videos, interviews and orchestration by Taryn Simon

Produced by Fondazione Prada for the “Human Brains: It Begins with an Idea” project

For some of us it helps us understand more and better.

As always, it is culture that has given people optimism and hope for the future.

And also to help undergo this shift in consciousness that we need now just to move forward.

I’m very curious about where this road forward will take us in five years. And for the very first time in my life, I have no answer. I have no idea. It is extremely unsafe.

We should somehow adapt to this and learn to navigate uncertainty.

What I strongly believe is that we have to trust artists, filmmakers, people from the theater, and people who work in the cultural fields in general. They should be trusted more than ever.

Do you think there still is truth in art?

What is the truth? I’m not sure if this is the right term, “truth”. Even a lie can be sometimes quite helpful. Truth...? But there is hope. Culture always goes in parallel with hope. It does not want to destroy or damage you. It wants to construct something. Even if it is deconstructing. That is the idea with deconstruction – to construct something new.

Exhibition view of “Human Brains: It Begins with an Idea” at the Fondazione Prada, Venice

23 April – 27 November 2022/ Photo: Marco Cappelletti / Courtesy: Fondazione Prada / Hieronymus Bosch. The Extraction of the Stone of Madness. c. 1501 – 1505, oil on oak panel / Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid Exhibition copy

If we go back to neuroscience, we are exactly what we see; what we have seen throughout our lives. How do you see the role of education today, and of art education particularly?

That is a good question. I can only say that, living in Germany, there has been a great loss in education in general. It is unbelievable. And this is not just the case over the past five years or so – it started at least 30 years ago. Also in Germany, in German society, politicians do not give enough attention to how children should be educated. This is a big, big loss.

But do you see some changes? Has anything begun to change?

I doubt it. I see some progress, but it is not enough. I do not know how it is here in Latvia.

It is the same.

It is the same everywhere, I guess. In the Western world for sure. But you can create the future only through education and by giving the best education possible to young kids – it is the only thing that can really change the world.

I recently had an interesting discussion with the psychologist and neuroscientist Richard Davidson – he’s done several meditation studies with the Dalai Lama and says that neuroscience is still in the kindergarten stage in terms of what we know about the brain.

What we know about the brain is nearly nothing.

It really is almost nothing, but nevertheless, it’s more than it was a hundred years ago. Davidson said we know nearly nothing, but we do know enough to act – yet we are not acting.

What is known is how easily you can manipulate the brain. We have known this for years. And the tools we have created for manipulating the brain are becoming increasingly advanced. I’m very much afraid of this. How will this influence education? How will it influence the thinking of young people? And yet we are just at the very beginning of it.

We already know that great manipulations can be done in cinema, for example. And that in other visual arts, such as in staging exhibitions, you can also manipulate the audience.

Absolutely. At least for me, in the analog world – by doing exhibitions – I have always wanted to influence the audience. By challenging with provocation through sound, by what they could see, or by what they could experience. It is about how to strengthen one’s thinking or boost imagination. But now, new and different tools are being continually introduced, and this is something else because it is not limited by humans thinking about how to manipulate other humans. These techniques are becoming increasingly powerful and it could is become dangerous. I have known this since I have worked on this exhibition [about the human brain]. It is frightening how easy it is to manipulate the brain.

Your persona is always associated with something huge: large-scale projects, big spaces, and many, many people being involved. Do you sometimes feel like a conductor who needs an entire orchestra in order to perform?

In the beginning, I started out in a rather small space: 10 by 10 meters, and 10 meters high, so a perfect white cube. But over time, I felt increasingly ready to... The size of spaces was never a problem because in the end, you have to fill it. But how should you fill it? You can fill it with very few things, with small ideas that might become very good ideas. Or the other way round – you fill it with masses of words, but then maybe you fail with the initial idea. I loved it becoming more and more complex. And the more complex the thinking process, the more I was convinced that I had to work with a team. It was not about me as a curator. Yes, you start with an idea, but then you need partners as the range of ideas expands and becomes more complex. And this is amazing if you have the right people to work with. But you’re right, maybe it’s more like conducting or coming up with an idea, and even letting other people realize the idea. I am becoming more aware and relaxed about these things.

Exhibition “The fabulous world of Walter Bosse” at the Berlin gallery “Brutto Gusto” curated by Udo Kittelmann.

Photo from Udo Kittelmann's archive

And about your ego as a curator as well?

Absolutely. But I still have to do it. There is the will. After the Human Brains project in Venice, I thought: “Wow, now I really need a break.” And I decided not to work for a while on any big projects. When I stopped being the director at the National Gallery about three years ago, I thought about what should be my last exhibition while still in the position as the director of five museums. I came up with the idea of showing ceramic pieces by Walter Bosse (1904-1979), an Austrian ceramicist, and I asked a small flower shop in Berlin if I could show the pieces in their shop. This was my last exhibition as Director of the National Gallery in Berlin. And I did not do it within the institution – I did it in that flower shop. It was amazing and the owner of the flower show has never seen so many visitors before.

Because art went outside of the museum, out of the institution.

Exactly. Some people do not see ceramic as an art form, but I do not accept this, hence I do not believe in hierarchies; I never have.

You also tried to break hierarchies with the brain exhibition.

Absolutely.

You said that after the human brain exhibition, you were totally exhausted and in need of a break. What are you doing to “clean” your mind, to allow fresh ideas to come in?

Actually, I do not have the feeling that I have to clean my mind. As I said, life is my sandbox, and I’m always in it. And sometimes somebody comes and destroys my sandbox – what I have built there. That is okay; you get used to that. Because you know that you can start with something else. And that is it.

You don’t ever like to “clear the table”, so to say?

Yes, sometimes I need white walls in my office. So I take all the papers, everything that I made during my research, off of the walls so I can start again with new ideas. And it is still fun. But I’m always curious about what will be the next project, the new change-over. So I take some breaks in between.

Udo Kittelmann. Photo: Aleksandra Wagner

What challenges are you facing at the moment?

I’m curious about and looking forward to seeing the new production by Tino Sehgal, a dialogue with El Greco in Spain. I have always dreamt of doing something with El Greco. But when it finally happened, I thought it would be a good idea to invite Tino Sehgal to come up with a new production in dialogue with El Greco.

When is this going to happen?

In October,at the Centro Botin in Santander, which is designed by Renzo Piano.

You have always been interested in the so-called white spots – discoveries within different fields of art.

Yes, absolutely. About three years ago I discovered, by coincidence, Heidi Manthey. She is now 94 years old. She does ceramics, porcelain, and faience. Amazing. She is from the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) and was a star there. I included her in this exhibition of 31 women. This is the very first time that her ceramic pieces are part of an art exhibition. I hope that now she will also be appreciated in the art world because the art world usually says: “What, ceramics? This is handcraft, it is not real art”. But it is real art! GDR, as I guess all socialist countries did, had a very different understanding about high art and handcraft. They were both placed on the same level. Wow! We really need to fight for this! Again, I do not believe in hierarchies, but I believe in what is good and what is not good. Yes, it is true. When I look back, for so many years I always tried to push artists, both women and men artists, who had, in my understanding, been totally under the radar.

Speaking about how art could help us in these times, one hurdle we are facing is that because we are so distracted by all the information around us, when we are in a museum or anywhere else, we no longer see the art. We just pass by it or spend just a fraction of a second in front of each artwork. How can we relearn the right way to look at art?

Since the pandemic, an increasing number of museums are weekly hosting yet another event, another performance, another concert. And, again, they are not grasping the idea that a museum should be a place where you can take a break, a place where you can shut down the high speed of life outside of the museum. You know what I mean? It is unbelievable. In Berlin, every week there are new events taking place at every other institution.

And one does not have the time to contemplate.

Exactly.

How can we return to this? Because this is what we desperately need.

It also has to do with our digital media. Because if you always have new events taking place one after another, you will get many more likes than if you just have one exhibition that lasts for three months or so. You double and triple your accounts with these likes. I guess it is no longer about how many people come to see the event – success is increasingly being measured by how many likes you get. And this, again, is manipulation – how you can make a lot of friends/followers just through images.

It looks like what we need is a huge power cut, and then maybe we can restart.

Yes. This became very obvious to me when I initiated the exhibition with Anne Imhof, a great character and personality, at the Hamburger Bahnhof - Museum für Gegenwart. In about one week or so, 20- to 30-thousand people came to see her production. And it was very much made for taking pictures. Every picture you took was an amazing picture, perfect for sharing among social networks. Again, it was about manipulating with images.

Was the show successful from your point of view? Did the audience get the message of the idea of the exhibition?

Oh yes. Absolutely. I understood that this moment was about the spirit of our time, and everybody could feel it. It was like a big rave. But usually to get into the groove of the rave, you need to spend hours there. But with her performances and productions, you immediately “get into it”. Because it’s not just about music. It’s about the atmosphere that she creates – it’s about sound, it’s about bodies, it’s about what you smell, what you see. It’s amazing.

But did it encourage the people who posted images on social media to think about everything you mentioned? Did they become more knowledgeable?

The ones that joined in on these evenings, who took these pictures themselves – definitely. Others... I have to think about it. I doubt it. For them, perhaps it was just a message that was sent through images. Maybe. I do not know… Again, going way back into my past, when I was13 or 14 being in school, there was a concert that I saw by KRAFTWERK. This short concert broadened my spectrum; it created fantasies in my brain. So you have to take every situation as it comes because it just might have the power to change your thinking, your attitude, your spirit, your wisdom, or whatever.

Just allow it to happen.

Yes. That is what cultural places should be about. There should be no rules. There should be, in the best sense, no expectations. Just let them do it.

Title image: Udo Kittelmann. Photo: Aleksandra Wagner