Laughter or Truth?

A conversation with the Skuja Braden art duo

The Skuja Braden art duo (Ingūna Skuja and Melissa Braden) was born twenty-two years ago, when two different cultures and two individual personalities met and joined forces. Ingūna Skuja, a Latvian, is an alumna of Latvian Academy of Art; Melissa Braden, an American, graduated from Humboldt State University in California, known for its modernist and post-modernist approach typical of the American system of art education. These are the creative crossroads that produce painted porcelain objects, recording with equal artistic expressiveness both events in the global airwaves and their personal life as a couple ‒ as well as the imprint of the one on the other. Every event that strikes a chord within the emotional system of the two artists gets translated into unique porcelain shapes.

The two decades of collaboration between Skuja and Braden have resulted in 43 solo exhibitions shown in different corners of the world; the most extensive one to date ‒ entitled ‘Samsara’ ‒ was mounted last year at the Museum of Decorative Arts and Design in Riga. The show, conforming to the pandemic-era restrictions, was opened and closed without a proper vernissage or finissage; on the other hand, it was able to transform from a public real-life event into a virtual one: part of the featured works were digitalized. During the short time when state of emergency was suspended in the country, visitors had an opportunity to view the exhibition in person.

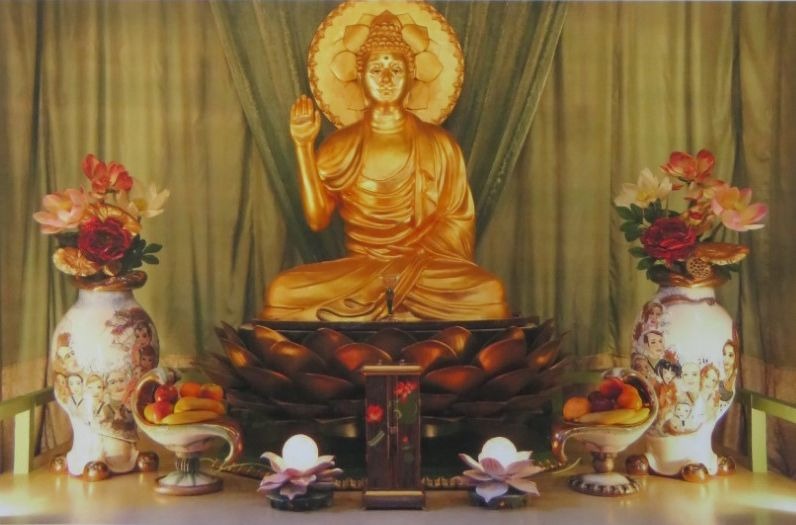

Choosing the subjects of life and death as the central axis of the show, the artists use over 200 porcelain objects with their baroque asymmetry, abundance of decoration and a certain dose of eccentricity and emotional expressiveness to illustrate the humanity’s errors and delusions on our path to the future. Recording personalities and phenomena in a blunt and to-the-point manner, with great artistic expressivity, Skuja Braden are knowledgeable and witty in their appeal to come to our senses and use some elementary reason ‒ to search for healing, mental balance, equality, compassion and all-embracing love. As a suggestive pointer to a road we could follow, the viewer encounters the centrepiece of the exhibition, a Buddhist-style altar dedicated to Ingūna Skuja’s mother Ilga Skuja (1923‒2019).

Skuja Braden. Exhibition ‘Samsara’ at the Museum of Decorative Arts and Design in Riga / work ‘Ilga’s Altar’, 2020. Photo: Gvido Kajons

The ‘Samsara’ exhibition has brought the creative duo Skuja Braden a 2021 Purvītis Prize nomination with a special mention of ‘Ilga’s Altar’, the central part of the exhibition. The exhibition has been recognised as a significant event on the Latvian visual art scene.

The following conversation is something like an emotional portrait of the two artists. We are talking in a Zoom virtual communication room, and the connection is failing from time to time on either side of the conversation. Ingūna and Melissa finds the strongest signal on the second floor of the house, which is where we also find the artists’ best friend and one of the main stars of their character list, an English setter, white with orange flecks, comfortably settled on the sofa. Our conversation involves lots of laughter, some tears and yet more laughs.

When the conversation is over, Skuja Braden will go back to their recently started projects; this time around, they are focusing on Ancient Greek mythology. The artists point out that it is a system deeply embedded in the Western culture ‒ both in the society’s ways of defining itself and in the principles that shape relationships between men and women. They also have to finish the works planned for the traditional Purvītis Prize exhibition. Ingūna admits: “There is this feeling that Mom is still helping us all the time. She has also helped us get as far as this Purvītis Prize nomination. We never hoped to achieve that.’ And it was announced in early March that Skuja Braden will represent Latvia at the 59th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale in 2022.

It has been a year since the pandemic imposed its rules on the way we live. What has been its impact on your life and your daily routine?

Ingūna Skuja: This time has given us an opportunity to adopt a calm rhythm in our work. We don’t have to rush anywhere; we don’t have to show up anywhere. Even the modelling classes I teach my students at Aizkraukle Art School take place via a video link on the E-klase remote learning platform. And even the car is currently broken down, but before that we could hardly use it because of the snowdrifts. We’re good.

Melissa Braden: This has been a surprisingly productive time. You Latvians have this custom of spontaneously dropping by for a visit, just for a cup of tea and some cookies. But I must confess that sometimes, when we are in the middle of a bigger project, it may disrupt our work a bit. No-one has shown up here for some time now.

Have you tackled the subject of the virus in some of your this year’s pieces?

I.S.: Not really. After the ‘Samsara’ exhibition many of the pieces were sold, and now the Purvītis Prize show is approaching really fast – and we have to replace them. Which is why we mostly need to stay within the same mood that the viewers could experience at the original exhibition. We are currently focusing on ‘Ilga’s Altar’ but also working on our next solo exhibition.

M.B.: We were preparing for our exhibition at the Design Museum for a whole three years; the work was intense and focused. Now, when it is finally over, there is this sense of relief ‒ as if we had graduated and were able to do whatever we pleased.

Flocked Vase, Westerwald Museum Collection | Zuzeum Collection

And yet ‒ by the time the exhibition was reopened, a corona virus-inspired vase had already found its place on a podium.

I.S.: The exhibition was closed for two months, and there was enough time to contemplate the subject of the corona. It was clear to us that we had to do something with it. We had previously made a hydrangea or snowball vase as a direct reference to the original 17th-century Meissen Schneeballen china vases. We wanted to revisit this style because at the moment it seemed strikingly reminiscent of the corona virus.

Alongside the corona shapes, the vase also features caricatured images of various political leaders. Could you tell a bit more about the general message of the piece?

M.B.: As we were watching the pandemic invading the world, we noticed that most of the countries that were hit the hardest were those controlled by dictators. So we decided to cover the whole volume of the vase in portraits of dictators ‒ to show that they are also like a virus infecting global public health. The Latvian title that we gave the vase was ‘Kroņa vāze’ ‒ literally, ‘Crown Vase’. As we all know, the word ‘corona’ means ‘crown’ or ‘wreath’, and while ‘corona’ is sometimes used in English referring to the head of a man’s penis, ‘kronis’ in Latvian is also the wreath you place on someone’s grave. And so consequently the petals of the snowball were replaced by shapes of the corona virus, each depicting a contemporary dictator ‒ Viktor Orbán, Recep Erdoğan, Idriss Déby, Kim Jong-un, Vladimir Putin, Bashar al-Assad, Omar al-Bashir, Xi Jinping and Donald Trump. The individual viruses are enveloped by skulls of the victims of this disease, as well as a porcelain Buddha, who is omnipresent and helps anyone find enlightenment.

I.S.: By the way, the filmmaker Ivars Zviedris was at the time looking for interesting stories about the things people were doing during the pandemic, and there was this idea of filming the process of creating the vase. Sadly, there was a little misunderstanding ‒ while we were waiting for his call, he was waiting for ours, but by the time it resolved, the vase was ready. It was bought by the collector Jānis Zuzāns. It would have been great if Zviedris had recorded the story of the vase from the beginning to the end ‒ including the purchasing of the Corona Vase on the day of the reopening, complete with exotic market-style haggling and much ado.

You have been living and working in Aizkraukle for over ten years now. What does this remote existence mean to you ‒ being physically distant from the art, culture and social processes and events in the capital?

I.S.: You now, I’m glad we already did all that years ago, when we were still living in Riga. My bohemian life started when I first came to Riga and did not end until 1999 when we both went to live in the United States. Director Egils Mednis recently shared a video from twenty-two years ago where we were sitting in front of Čiris Gallery in the Bergs Bazaar, waiting for the opening of a Roberts Koļcovs’ exhibition.

M.B.: We are gathering outside, drinking champagne… Kaspars Brambergs is wandering around; we are laughing and talking with Silvija Spūle, who was running the gallery at the time… It was so long ago! As time goes by, you forget how young you used to be.

I don’t think we would have moved here if Ingūna’s mom had not needed our assistance. Of course, what we were thinking at the time was ‒ no-one would know about us anymore; it would take an eternity for us to become part of the Latvian art circles, and so on. We would be living in the middle of nowhere, in this bloody Aizkraukle, and it would be over for us. In reality, it proved to be a real blessing. The process of creating our art is very work- and time-consuming; here we are not distracted by rumours, scheming or anything else. Moreover, during these thirteen years that we have been living here, we have always made a point of making the most of each trip to Riga. We try to see every exhibition, theatre production or film.

I.S.: And the nature is so beautiful here! Look ‒ this is what we get to see outside the window (turns the laptop’s webcam toward the window)! There is the water tower and Aizkraukle church in the distance. This feeling of space!

Does nature inspire you?

M.B.: Definitely.

I.S.: I would say that people are our greatest inspiration. Mundane situations and things that happen in the world.

M.B.: Yes, things that upset us and things that make us happy.

I.S.: Because of the doggie, we go for walks in the nature, along the banks of Daugava every day. It gives us chance to mull things over properly.

M.B.: I would like to add that Ingūna is a great gardener!

I.S.: My uncle Egons Fridrihsons was a world-class gardener. He was the administrator of Mežotne Palace for 27 years and a Bearer of the Order of the Three Stars. He was breeding lilies and named one of the breeds after me, ‘Ingūna’. In Mežotne he made a path to the pharmacy, along which all sorts of medicinal plants grow. There is an informative sign next to each of the species ‒ and perhaps you may find exactly what you need right there, in the flower bed, without walking through the door of the pharmacy. So there was this time he had come to visit my mom and told me: ‘You are an artist, and I can see it in your garden as well. But you should now that beans would never grow in the same spot two years in a row.’ And he was right. One year we grew enough beans to eat all year long; the following year I sowed beans in the same bed ‒ and nothing! No beans!

Speaking of your reaction to everyday situations and world events, I must say that your approach to reflecting on these things is point-blank. How important it is for you to be so blunt and open?

M.B.: It is extremely important for us; we do not want to pretend to be someone we are not. Yes, the works sometimes are very straightforward, but if you look closer, there is also something else. For example, the titles: they may be double or even triple, and they point at various ways of viewing them. And purely physically as well, there are two or even more sides/facets to the pieces; there are several things taking place, several stories unfolding simultaneously. The works have several meanings at the same time.

I.S.: If Melissa could have a parallel career, she would be a comedian. And comedians, as we know, are very direct.

M.B.: If you strive to find the truth, you are direct. You do not try and fool anybody. There is enough insincerity in art as it is. ‘Let’s make some kind of stuff and give it a contrived title. That would be so clever and witty!’ Sorry, I think there is nothing clever about it, because nothing has really been created ‒ only a title has been made up. Truth matters more to us.

Regarding the comedy… What is the role of joke in your works?

M.B.: The things that make us laugh ‒ they are genuine. They have made an appearance of their own accord, uncontrolled. We cannot control laughter. We can control almost any other of our emotions but not our laughter. And when do we laugh? At moments when we experience a truth! At moments when suddenly we are visited by a revelation about something we may have never even properly thought about. Sometimes Ingūna and I would be telling each other some stuff and suddenly burst into wild laughter; and it becomes obvious then and there that we simply must make a piece out of this. And we do laugh a lot.

Altar of the Throssel Hole Zen Buddhist Abbey

You are both practicing Zen Buddhists. How does directness and a certain rebellious spirit resonate with the Buddhist teachings?

M.B.: We are not monastics. And even monks have sometimes been rebels. Buddhism is very direct and honest. You try to be a good person and act in the right way: you don’t hurt anyone; you don’t lie, and you don’t manipulate people. We follow these rules and practice them, but at a time when so much pain, falsehood and manipulation is being generated in the world ‒ we have to stand up and confront it. We are not going to accept all these things that happen quietly. And hence I don’t think I really see us as rebels.

A warm summer day under an apple tree with Ingūna, Ulla the dog, and Ilga holding a kitten

Have you had to defend yourselves as well?

M.B.: Yes. We have been together for 22 years; we have no intention to hide behind a corner and pretend it isn’t what it is. That would be ridiculous. So we cannot get married in Latvia ‒ fine; if that’s the law then so be it. But there are so many hostile people here! In Aizkraukle there are people who wait for a moment when we are in the street and then approach us. We have been thrown at with shit bags, our dog has been kicked: we have experienced quite a lot of physical violence. In this respect we are already like, whatever! We are moving! Finally!

I.S.: Aizkraukle is the land of my childhood, and sometimes I happen to bump into my teachers, people who have taught me. And I have asked them: what was I like as a child? One my teachers confirmed that I had always fought for justice. I am not going to stand by if somebody is being mistreated, that’s true. My father used to tell me when I was a child: you are just like your mother! Mom was also always fighting some battle or other. She was defending the Latvian language. She hated seeing it being misused – on TV, for instance. She used to underline mistakes in the magazines: ‘It’s not kartiņa, it’s kartīte!’

Your tribute to Ingūna’s mother, ‘Ilga’s Altar’, struck a powerful chord with the viewers at the ‘Samsara’ exhibition. Many were pondering lots of unanswered questions long after the visit. Could you outline the process of making the piece and some of the decisions you made at the time?

M.B.: I can describe the natural development of the idea, the way things happened. We lived with Ilga and took care of her. During her final three years, Ilga’s senile dementia progressed rapidly. She seemed to drift in and out of reality. We were already working on ‘Samsara’ at the time, and there were some plans regarding a piece called ‘Ilga’s Closet’ ‒ about things hidden in Ilga’s closet. And then she passed away.

I.S.: Her name Ilga happens to coincide with the acronym for International Lesbian Gay Association (ILGA). So it’s like ILGA coming out of the closet!

M.B.: Ilga died, and the closet transformed into an altar. We had previously made porcelain altar ornaments for the Throssel Hole Zen Buddhist Abbey in the UK, a monastery we visited as part of the ERASMUS programme. The idea we had now was to create an altar in memory of Ilga, with her face on a vase. We wanted to make her mask while she was still alive, but we ran out of time… So now we had to make her death mask. Posthumous portraiture has a long history, from Egyptian mummies and Roman death masks to Victorian post-mortem photographs of deceased loved ones. Ilga’s portrait is contemporary art.

Ingūna, Ilga and Melissa at the Karma Coma exhibition at Kalna Ziedi Aizkraukle History and Art Museum, 2010

Could I ask you to share the emotional background of making your mother’s death mask?

I.S.: Mom had initially wanted to be cremated, and we thought about making an urn that we would donate to the museum. That way Mom’s ashes would end up in a museum! However, she changed her mind; she wanted to be buried in her family’s burial plot, so we came to an agreement with her that we would make a death mask. Mom was very mobile until the age of 96. On her final day at home, we even went for a walk in the snow… until she suddenly felt very ill. They operated on her at the hospital, and she lived for five days after the operation. On the very day when we were about to got to the hospital to bring Mom home, armed with chocolates and brandy as a thank-you-gift for the doctors, they called me to tell that she had passed away.

Skuja Braden. Exhibition ‘Samsara’ / work ‘Ilga’s Altar’ at the Museum of Decorative Arts and Design in Riga, 2020. Photo: Didzis Grodzs

We had until midday to make her death mask. And we could not find the gauze we needed at the pharmacy. I was a bit hysteric; I was scared that we would run out of time. The doctors eventually gave us the gauze we needed. At the Jēkabpils mortuary they told us that they had to put her dentures in and sew the mouth closed first, also dress her. I took part in all of that, and the whole process was recorded on video. You can only do something like that to someone you really love. It was like a farewell in a way. It was the last time I could tend my Mom. I used to apply her Nivea cream to her face before bed, and I would always tell her: ‘That’s so you would look lovely in the coffin! No wrinkles!’ And she would always laugh.

M.B.: We created art out of this final moment.

I.S.: We also painted the coffin ourselves.

M.B.: We were busy getting things done, there was no time for tears. It is now that we do the crying ‒ when we talk about the time or watch the video. Many people have told us that they found the video deeply moving. That it had been a very special experience for them.

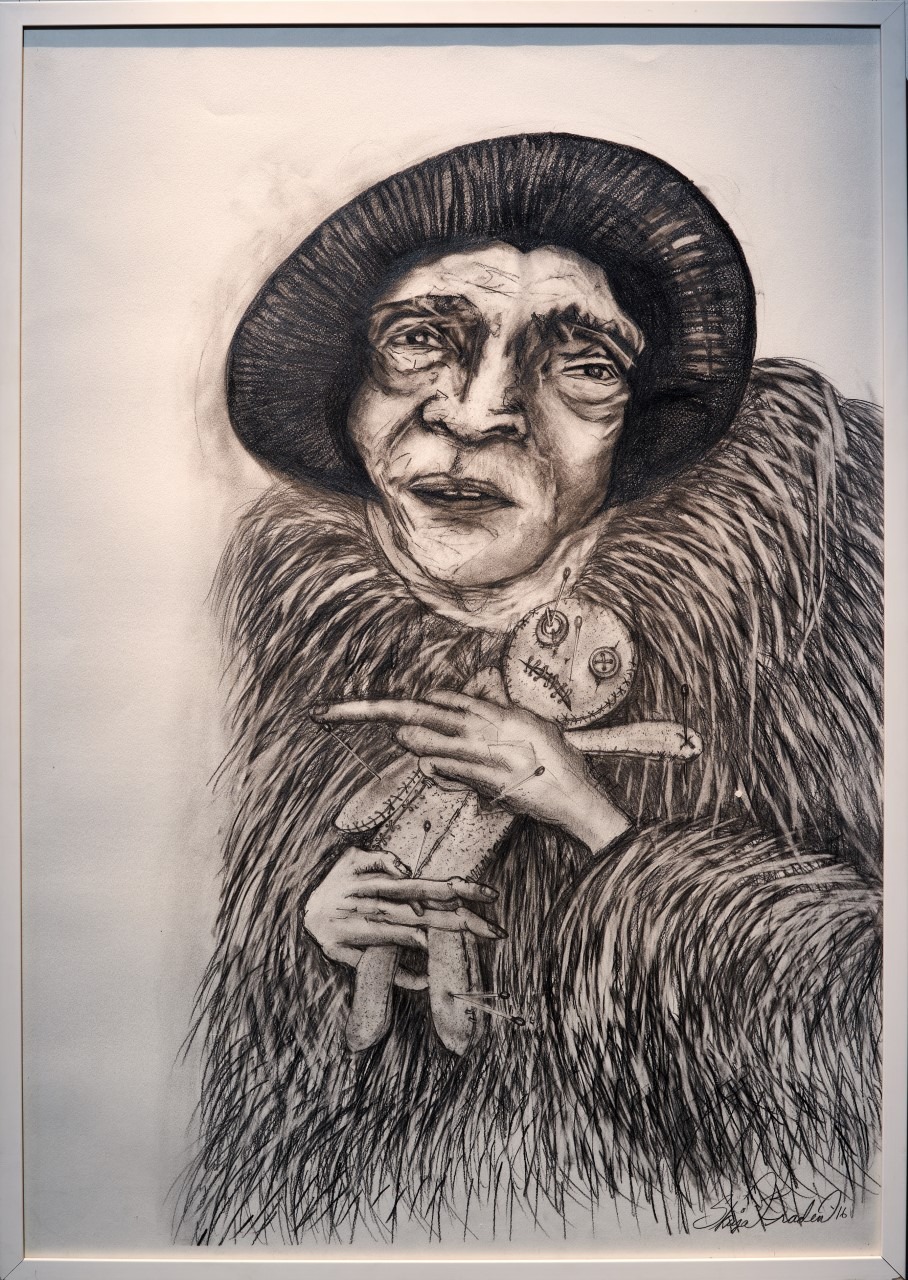

Drawing Ilga’s Regret shown next to the Altar at the Samsara exhibition

Your way of recording the reality genuinely strikes a profound chord. It is hard to remain indifferent.

M.B.: Yes, that is what we wanted ‒ for the exhibition to be not just an opportunity to view beautiful objects or a wonderful concept but also to feel these moments in our life. The altar was the realest of all the moments in the exhibition because it is about things that really have happened.

I.S.: It reminds me of the big skull we were making at the time when Mom was already having real difficulties with walking. Mom was sleeping in the living room, which doubled as our studio. In the evening, when we were done, I covered the skull with a bag. Mom had to get up at night and she held on to the skull. The clay was still soft. I yelled at her to let go of it, but she didn’t ‒ she walked on, dragging the skull along. The shape got deformed, of course, and we remade it. It struck me later that perhaps we should not have.

Skuja Braden. Exhibition ‘Samsara’ at the Museum of Decorative Arts and Design in Riga, 2020. Photo: Didzis Grodzs

M.B.: But we showed a drawing at the exhibition where Ilga was wearing a fur coat and holding a voodoo doll full of pins. In the picture she has a monkey’s arms, which symbolise the insane passion for sewing that came upon her as the dementia progressed. She would sew everything together ‒ our socks, so we could not get a foot inside, our underwear ‒ until it started to resemble a blanket; she would cut the sleeves off our sweaters to make them look smaller… She would leave needles all over the place. I kept stepping or sitting on them all the time. And so we came up with this idea that we should get her to make a voodoo doll. Let her sew, because that’s all she wanted to do. But she did not manage to finish it… And then we realised that she had been defeated at last.

Every event in our life eventually ends up as an artwork. If someone asked how we would describe our art, I would say ‒ yes, perhaps stylistically it is a kind of minimalist baroque, but it is also always inspired by life through and through. It has nothing to do with realism and everything to do with the reality.

Are there any subjects you are perhaps not yet ready for? Subjects that are a challenge of sorts for you?

M.B.: I must say that I cannot think of any subjects that are a challenge for us, which we are afraid or not ready to explore.

I.S.: Corruption perhaps?

M.B.: But we have done corruption already!

I.S.: Well, yes, you’re right. I remember this incident regarding our Putin vase, when our Russian neighbours approached us and said: ‘You must like Putin very much!’ They really thought we were depicting him out of love. They do believe that Putin is a good man and Trump is an honest businessman.

M.B.: It has to be said, though, that the local Russian population is a very specific one. These are people who originally came here to build the Pļaviņas hydropower station, hoping for a better life that never came. Their mentality is very different from that of the Riga Russians or the intelligentsia in Russia. This part of the Russian population… They are… I don’t even know what to call them… Rednecks!

I.S.: A minibus recently delivered the porcelain we had ordered from the UK. Our neighbour had left her car literally in the middle of the road, so the bus could not get past it. I went to ask her to move the car, and she started calling me names: ‘Lezbiyanka-obezyanka [lesbian monkey]!’ To which I responded by calling her Putin’s whore. Her eyes were like saucers. It was shortly after the film about Navalny had been shown on TV, and it must have made some sort of impact ‒ she must have started to see the light or something…

What does working as a duo mean for you ‒ in terms of idea development and producing the actual object?

M.B.: It happens naturally. Each decision is made based on the best solution we have reached through lengthy discussions. Working in this medium, you have to think a lot about the logistics of joining the various details.

Is it really four hands on a single object when you work?

M.B.: Yes, exactly. Whenever the form is more complex, we need the hands of both of us to physically put the object together. And you have to work fast with porcelain. Often, when we are making large objects, particularly free-standing vases, it is truly a matter of teamwork. One of us is holding, the other one is squeezing together, and then something starts to come apart, then one of us starts yelling, the other one starts yelling, and then we squeeze it together…

Incredible!

I.S.: The Design Museum made a 10-minute video “How Art Is Made”, which can be viewed on YouTube. They, too, could not believe it could work this way.

M.B.: In the USA, around 2005, we made life-size babies for our solo exhibition entitled ‘Babies’. When we were making the first one, we thought we would never manage to get it done: ‘Aargh, it’s not holding together! It is falling apart any second now!’ It literally was like two women giving life to a baby! It took us fifteen hours to make a baby, the both of us grabbing, holding and squeezing! That was the time when we really started literally working side by side.

Porcelain is a difficult material specifically for sculptural forms. You work in a distinctly original artist’s technique. Does the material still hold an undiscovered secret for you?

I.S.: The material is infinite. And the fear that we might not manage to bring to life the idea we have in mind in this material ‒ it is always present. We have this joke that before we start working, the order on the table must be as perfect as in the operating theatre. The workspace must be set, the instruments must be on hand, the room must be empty so we can move around freely. We must always have respect for the process. But every time we finish a new piece we think it is the best we have ever made. It is a rush of adrenaline driving you to keep going.

M.B.: Yes, without a shadow of a doubt, it is the most exciting moment ‒ creating something new, trying something we have never done before. The element of not knowing. And I must say we have finally reached a point where everything is about the ideas ‒ about creating things we have never made before.

Do you believe in a certain stage of maturity for an artist when they create their most truthful, most complete work? When they fulfil their artistic mission?

M.B.: Yes, youth comes with strength and energy, with huge ambitions and a desire to learn. But you have to get done a lot first and make a lot of mistakes, because mistakes are the best lessons of all. And then finally comes a time when you have done enough, reached a level of understanding you can compare to an encyclopaedia of experience. At that point, it is really starting to get interesting: the artist finally starts making works about the things they have genuinely wanted to convey.

Skuja Braden. Exhibition ‘Samsara’ at the Museum of Decorative Arts and Design in Riga, 2020. Photo: Didzis Grodzs

Do you think that an artist is someone special? A chosen one?

M.B.: No, absolutely not!

I.S.: A doctor is also a chosen one. An artist is a profession like all the rest.

M.B.: Yes, I agree that it is a profession. But there is also something in our DNA. Something we don’t even suspect. And yet the artistic gift keeps surfacing in every generation. There is this TV show called ‘Finding Your Roots’. It is a genealogical examination of the roots of famous people: where they are from, who they are. And it often turns out that the lineage of a prominent professional features a number of great masters of the same craft. As often as not, they don’t even suspect that the thing they are doing is literally in their blood. It’s in their genes.

As a student in America I asked my professor what the most important thing was to become a successful artist. She said that hard work always makes a talent shine. And that people who take their talent for granted may lose this gift. And I have seen it happen in life. It is not about being a chosen one; it is about hard work.