An environmental book club that ended with an exhibition

Maria Helen Känd / photos by Marje Eelma

The exhibition “Bambi Project” at the Kogo gallery in Tartu

With its year-long program “Ecology – Economics”, the Kogo gallery in Tartu joins the global art discussion that has gained momentum in the context of the climate crisis, focusing on concepts such as green politics, social inequality, the Anthropocene, and posthumanism. Gallery curator Šelda Puķīte invited six artists to an environmental book club that gave rise to the “Bambi Project” (27.08.2021–09.10.2021) – a group exhibition inspired by the story of the fairy-tale deer Bambi. This review asks: about which subject does the project tell us more – nature or pop culture?

After the First World War, the short story “Bambi, a Life in the Woods”, originally intended for adults, was published in 1923 by Felix Salten, a Viennese modernist and Zionist. In 1942 the popular book was made into an animated film by the Walt Disney Studios, thereby enshrining the moralistic fairy tale into pop culture and turning it into a bible for young environmental activists.

Encountering a young generation of artists from the three Baltic states in Tartu as they find their own interpretation of the Bambi story feels refreshing. The curator has grasped the similarities between the style and signatures of the six artists well, with works that courageously experiment with different techniques (from embroidery to concrete casting) and powerful metaphors. In the gallery’s exhibition room, one will find a balanced combination between the sculptural works on the floor and the installative pieces protruding from the walls. The space itself, painted in an enchanting dark green, absorbs the viewer like a fairy tale should.

A fairy tale or reality?

Whether you ask someone who is four years old or ninety, all humans identify nature as being green. This colour is both a biological entity – foliage and vegetation are mostly visible to us as green – as well as a cultural code for expressing environmental matters. In the case of Bambi's story and this exhibition, the personification of the animal kingdom and the anthropomorphic approach to nature come through. And although the humanization of animals is common in folktales, this approach deserves to be analysed in the framework of the Kogo gallery’s project.

Domestic animals, such as dogs or cats, do not detect green in the wild, whereas insects such as bees can see UV radiation and a richer colour palette than humans. Nature is differently perceived by other living organisms than usually expressed by human culture. Hawks do not happily greet the arrival of spring along with mice, and for ducks, rain really feels just like water off their backs. If the curatorial text of the exhibition states that the works of art are being presented in a “darkened, protective environment, where [they’ve] become a coherent ecosystem”, the human-centred undertone of such a statement evokes a slight dissonance, because from whose perspective and for whom is a green cube a protective environment?

The colour green is indeed entrenched as a symbol of nature, but observing the reality of our current living environment, it’s more of a bright orange colour that is shimmering in the skies of California and Siberia right now. If the walls of the gallery had shone in a shade of red, the bell would be tolling for all living organisms under merciless threat – both in the real natural world and in Bambi’s story.

Deer blood and the smell of fear

The exhibition does not speak or teach us the language of trees and flowers – an adaption skill that is preventing the complete destruction of ecosystems, as Estonian theatre artist Ene-Liis Semper emphasized in a powerful speech a few years ago. Still, the works convey nature's cry for help to an explicit extent.

Līga Spunde. "Gobo“, 2021, "Varjupaik rahule ja vaikusele“, 2021

Both installations by Līga Spunde effectively dwell on this critical topic. The installation that displays a woodcut image of a deer behind a thick glass case could be understood as a metaphor for the human desire to capture nature as property, much like it’s commonly done by hanging animal trophies or natural findings on walls. The interpretation changes with the accompanying text, which says that the artist has used real bulletproof glass – meaning that in fact the work intends to unarm humans as much as possible when facing nature. The second work, “Gobo”, fascinates with its twisted structure and powerful seriousness as the wooden engraving in the foreground – depicting an animal and a human in the company of one another – is supported by a neon pink hunting rifle in the background.

Rūta Spelskytė's installation

Ruta Spelskytė’s interest in alchemy is manifested in a Joseph-Beuys-like installation consisting of geological and animal findings. Parts of the sculpture – like dried deer blood – can be repulsive to a principled vegan, but if we believe them to be collected through natural death, the elements of these works are worth further exploration. The animistic installation delights with a subtle treatment of form and an exciting mythological background in which various natural substances are given meaning.

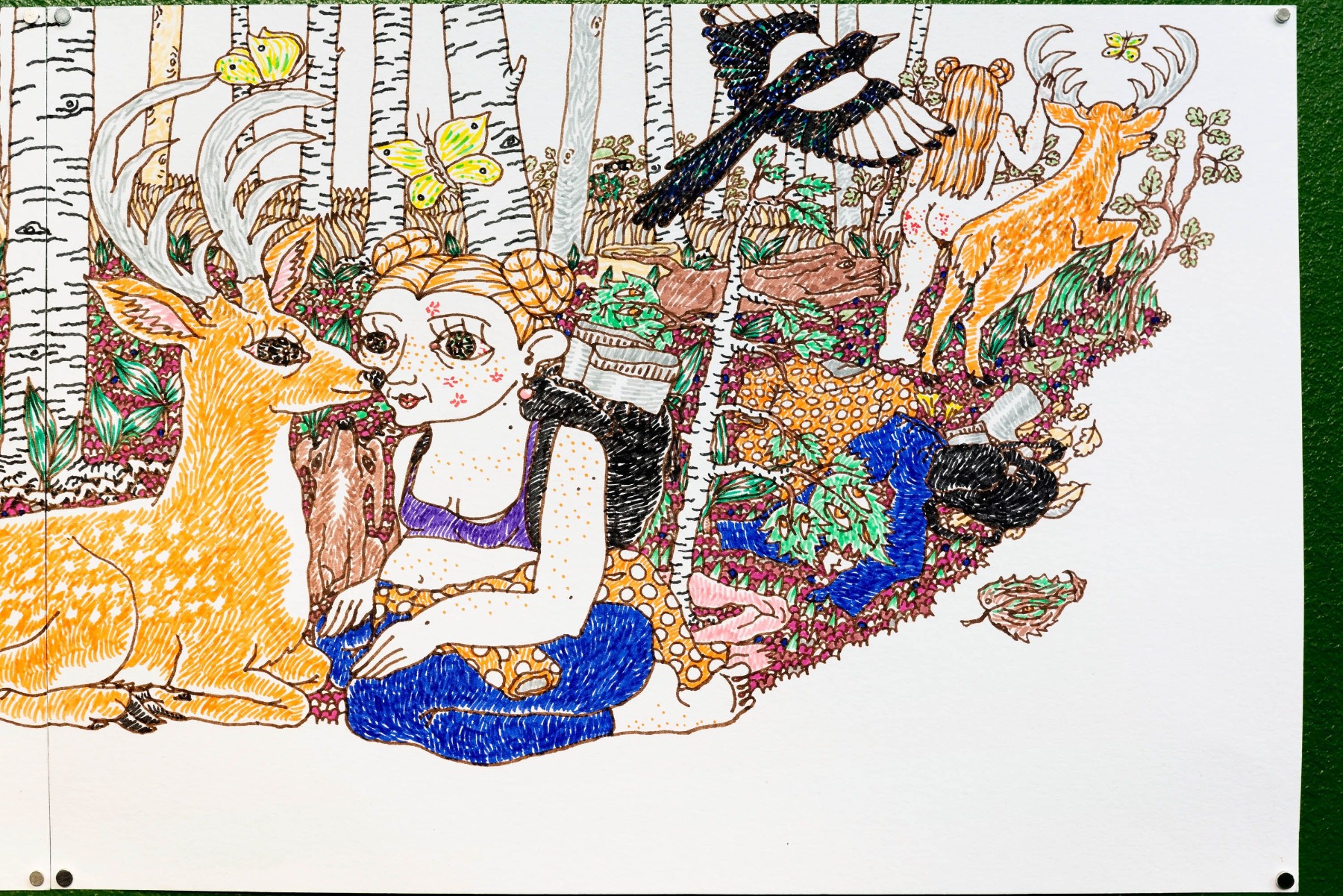

Ingrīda Pičukāne. Fragment from "Bambi _ Bambi“, 2021

Feminist artist Ingrīda Pičukāne tries to break down the stereotypical treatment of human and animal relationships in the Bambi story in which hunters hinder the friendly co-habitation of species. Unfortunately, by adding to the story a female character who goes to the forest to mediate with Bambi while the only human portrayed in the original story is a huntsman, Pičukāne reproduces the same binaries (i.e. man vs woman, man vs nature) which she aims to demolish. As powerfully shown in Werner Herzog’s documentary “Grizzly Man”, a friendship with a wild animal is not just a womanly matter; moreover, a peaceful existence with the animal kingdom is not always expressed in mutual understanding. Nature can be cruel.

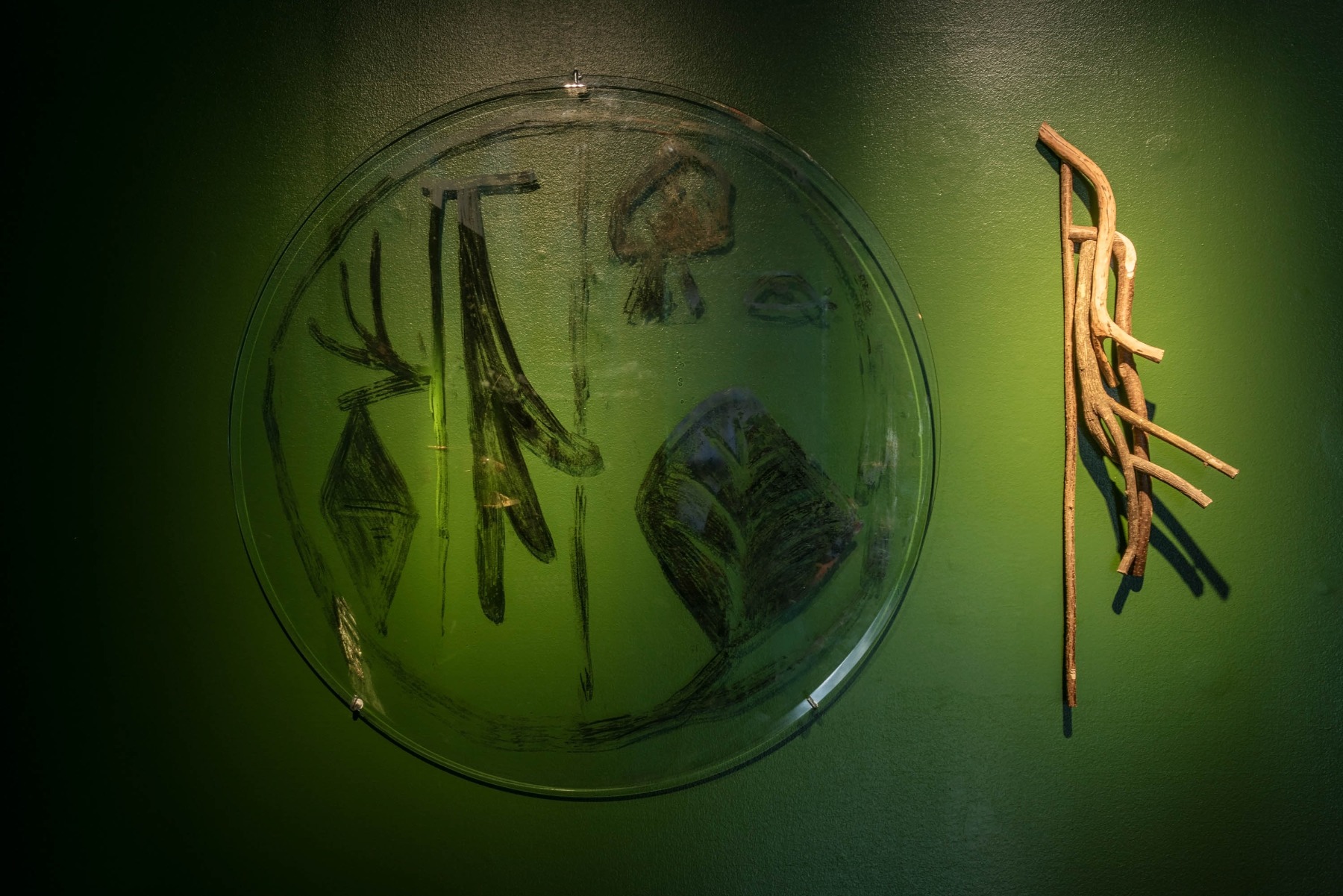

Žilvinas Landzbergas. From series "Udu“, 2021

Working holistically with traditional belief systems, Žilvinas Landzbergas has created a reflective painting surface and next to it, a wooden shamanistic stick. Here, the painting surface is no longer a mediator of something, but in new materialist terms – it has its own will and way of being. Landzbergas’ work is the most cognitively perceivable object in the exhibition and its interpretation would lead to unnecessary rigor.

Laura Põld. "Pealiskiht II“, 2021

Laura Põld’s hypnotically patterned rugs are again the closest to the seemingly irregular systems of organization we see in nature. Reminiscent of the yearly tree rings one can see on the cross-sections of a tree stump, these variegated rug patterns add energy and effect to an otherwise dark room. Eike Eplik’s concrete-casted and ultra-fine wire forest-form, on the other hand, aims to represent a delicate thicket of tree branches and trampled hay on which deer usually sleep, but the rawness and sturdiness of the materials only illustrates a total lack of fragility. This allows one to stick with the thought that without actual fragility, there is no nature, just the idea of nature.

Eike Eplik. "Isiklik ruum“, 2021

In summary, the “Bambi Project” is primarily concerned with understanding and playing with social and cultural phenomena. The exhibition involves abstract but still sign-based relationships between the artists’ interpretations, which are only figuratively ecological. Art does not have to imitate nature, even if nature takes artistic and artificial forms.

Bambi’s offspring will probably live happily ever after. In contrast, the depletion of ecosystems in our world today is a brutal and rapid process. The exhibition at the Kogo gallery maintains a socially critical tone, but at times it attunes to a fairy-tale atmosphere in which the viewer sinks into the strata of pop culture without focusing on the real dangers of nature.