Elīna Vītola Is Painting Again

Review of Elīna Vītola’s solo show at the Kogo Gallery in Tartu

In 2007, Elīna Vītola (Salacgrīva, 1986) took a break from painting in order to search for other interesting things in life. She tried advertising and graphic design to realize that painting was still the best.

Vītola had decided that she would become a painter at the age of 4. Alas, her parents only had two art books[1] at home and in the countryside (where she lived until the age of 12) there were not many opportunities to visit exhibitions. Nonetheless, her grandmother had an intriguing green and blue painting hang on the wall, which Vītola recurrently copied.

Once in Riga, she studied painting at the Art Academy of Latvia and started organizing different art events. Now, Vītola has an exhibition in the Kogo Gallery of Tartu (6.12.2024–8.2.2025). It is one of these exhibitions that visitors feel much stronger through the physical encounter with the works than as represented in the photo documentation.

Elīna Vītola, Paint Job. Yellow Ochre, 2024. Fresco on impregnated drywall, 130 × 90 × 4 cm, Paint Job. Kaput Mortum, 2024. Fresco on impregnated drywall, 130 × 90 × 4 cm

The Line. Fig. II. Third Configuration, 2024. Oil on canvas, 3000 × 3 cm, Document Fresco. Crack., 2024, Fresco on drywall, wooden frame, 51.5 × 41.5 × 4 cm. View from Elīna Vītola’s solo exhibition To Pay an Arm and a Leg at Kogo Gallery. Photo: Marje Eelma

The title is ‘To Pay an Arm and a Leg’. This English expression emerged in the early twentieth century referring to war injuries. In the context of the exhibition, it highlights the cost of life choices and a situation in which one has to pay an extremely high price.

The verb “to pay” itself comes from Medieval Latin, referring to the gesture of satisfying, pacifying and appeasing. This meaning died out by 1500, while the figurative sense of suffering and enduring replaced the old one. However, the actual remunerative connotation of paying was consolidated much later, only in the nineteenth century.

View from Elīna Vītola’s solo exhibition To Pay an Arm and a Leg at Kogo Gallery, 2024.

Photo: Marje Eelma

The exhibition uses this body metaphor (to pay an arm and a leg) to conceptualize the entropic ways in which history binds and separate people. The trigger of these paintings was the phantom of the artist’s great-uncle, the author of the painting at the grandmother’s apartment.

Vītola ended up digging into the life of an unknown relative who disappeared during the Second World War. In 1940, he was hiding from the Soviet forces; then he resurfaced in Riga during the German occupation working in the security police and, quite probably, collaborating with the Arajs Kommando (a notorious paramilitary killing unit active in Latvia during the Holocaust). Then, he disappeared again, eventually emigrating to the UK. The latest news told about a mental disorder and a psychiatric clinic supported by his brother, who also had fled to the UK.

View from Elīna Vītola’s solo exhibition To Pay an Arm and a Leg at Kogo Gallery, 2024.

Photo: Marje Eelma

Vītola’s archival research brought further unexpected discoveries. For instance, that the great-uncle had children with two women, one of them a Jewish refugee who used to serve in the German military canteen. Therefore, there were branches of the own family unknown to the artist. So, she established contact with the distant relatives, one living in Australia and the other in New York.

Elīna Vītola, Document Fresco. Pounce., 2024; Document Fresco. Measure., 2024. Frescos on impregnated drywall, wooden frame, 51.5 × 41.5 × 4 cm. View from Elīna Vītola’s solo

exhibition To Pay an Arm and a Leg at Kogo Gallery, 2024. Photo: Marje Eelma

Curator Ieva Astahovska has helped Vītola with the historical contextualization and the conception of the display, adding an extra leg and extra hand to the show. Kogo’s efforts to involve a curator and organize a public discussion in most of their shows is indeed commendable. Apparently, Vītola was doubtful about questions such as who owns the family past and who is allowed to tell it, and Astahovska (her former teacher) has been a good ear to the artist.

View from Elīna Vītola’s solo exhibition To Pay an Arm and a Leg at Kogo Gallery, 2024.

Photo: Marje Eelma

The show is decorated with a series of ribbons or cords, which serve to fix, hold and tighten the paintings. They appear, symbolically and materially, as a string that connects the present and the past. Interestingly, they come from the still-existing Lenta textile factory in Riga, which was transformed into a labor camp for Jews during the German occupation.

Elīna Vītola, The Line. Fig. II. Third Configuration, 2024. Oil on canvas, 3000 × 3 cm

Rolls of ribbons to be unfolded and to be cut; returns beyond meaning, bigger than us; Family shadows and silences with a blurry figuration; Framings, banisters and connectors, but also skeletons; Layers of time and materials sedimented despite us.

Even when the past has little use to explaining the present, it is nonetheless our past.

View from Elīna Vītola’s solo exhibition To Pay an Arm and a Leg at Kogo Gallery, 2024.

Photo: Marje Eelma

This is a painting exhibition; but one combined with subtle gestures of sedimentation and geneaology in order to expose the complexities of seeing and the reproduction and destruction of relations.

Here the past is made present with earthly colors, sedimented materials, and holes of different depths and sizes. The artist uses fresco techniques with quick-build construction structures; there are drywall sheets in addition to paintings on the wall. Also, there is a big hole, opening up a view into a previously invisible part of the gallery space, exposing the drywall-white cube structure of Kogo.

View from Elīna Vītola’s solo exhibition To Pay an Arm and a Leg at Kogo Gallery, 2024.

Photo: Marje Eelma

It is indeed dangerous when things resurface in the wrong way, when things that were not called back linger on phantasmagorically; then they strongly destabilize our living. Yet there also is a great learning in paying attention to what reverberates through us.

Pentimenti and phantasmagorias. The former term derives from the Italian pentirsi, meaning “to repent”. A pentimento is defined as the presence of traces of previous works or of an alternative composition beneath the surface. Traces that reveals the imperfections and bifurcations of the creative process. A phantasmagoria, in turn, refers to an illusions or deceptive appearance, as in a dream or as created by the imagination.[2]

Elīna Vītola, Document Fresco. Crack., 2024, Fresco on drywall, wooden frame, 51.5 × 41.5 × 4 cm. View from Elīna Vītola’s solo exhibition To Pay an Arm and a Leg at Kogo Gallery, 2024. Photo: Marje Eelma

Vītola remembered that her father always wanted to be a painter but that he became a businessman instead; Also, that when she was young, neighbors told her to have inherited the skills from her great-uncle. Apparently, the grandmother was unhappy with all that.

Like her great-uncle, Vītola herself is a craft-maker. “I spend whatever family budget available in canvases and painting”. The great-uncle produced applied art such as decorative interior paintings.

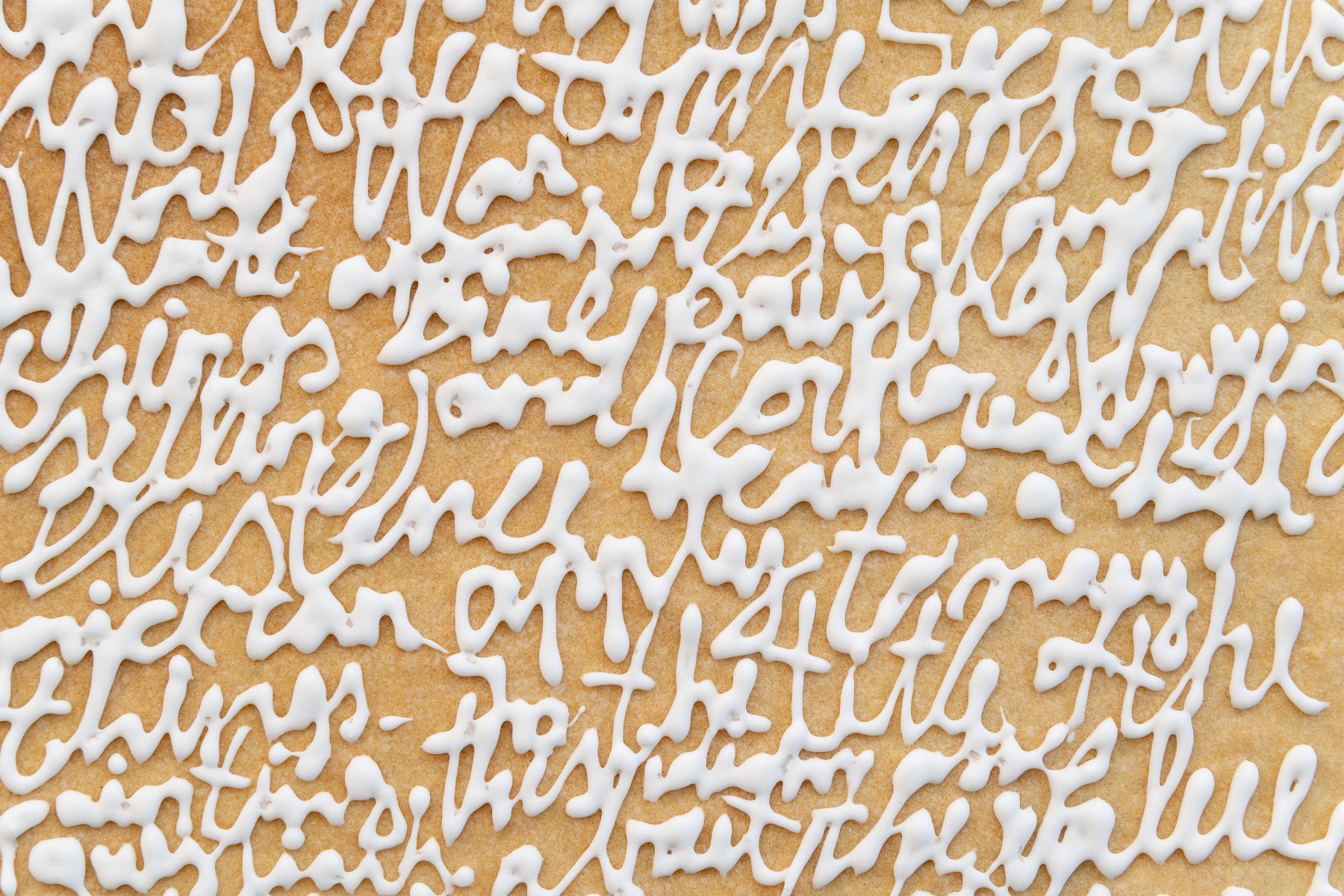

Elīna Vītola, To Pay an Arm and a Leg, 2024. Sugar cookie, sugar glaze, wooden showcase frame, 52 × 42 × 4.5 cm. View from Elīna Vītola’s solo exhibition To Pay an Arm and a Leg at Kogo Gallery, 2024. Photo: Marje Eelma

Instead of the artist’s position within the family tree, the exhibition reflects the Vītola’s connection to the family body. Not in a figurative sense, but as a technique du corp, as a self-fashioning instrument that gives shape to a particular corporeality (an equation of animality, materiality and the tasks we learn to perform).[3]

Vītola, the girl who grew up with two painting books at home, is inventing her own tradition. In this self-fashioned tradition, a technical conceptual search is important; not simply visually, but as an exploration of the physical properties of materials. We can also distinguish various elements of surprise; not simply doing things differently, but doing different things altogether.

Sometimes it is not necessary to understand things, but to imbue yourself obsessively in them.

Because creating is not copying, but the recombination of diverse pasts.

Because everything is painting.

Because Vītola has never stopped painting.

***

Francisco Martinez is an anthropologist dealing with contemporary material culture through ethnographic research.

[1] Lamberga, D. 1986. Klusā daba. Liesma; and Šmagre, R. 1990. Latviešu pastelis. Liesma.

[2] Boym, S. 2017. The Off-Modern. London: Bloomsbury.

[3] Mauss, M. 1973 [1935]. ‘Techniques of the Body’. Economy and Society 2: 70–88.