Nature constantly shows you that nothing is forever

Q&A with the artists Mari-Leen Kiipli and Eike Eplik, and curator Šelda Puķīte

Kogo Gallery, a contemporary art gallery based in Tartu, Estonia, will be participating in this year’s Liste Art Fair Basel (20-26 September), presenting the works of two Estonian artists, Mari-Leen Kiipli and Eike Eplik. Arterritory presents the following interview with the artists and the curator of the Kogo Gallery stand at Liste Art Fair Basel 2021, Šelda Puķīte.

Why did you choose the greenhouse as a metaphor for our time?

Šelda Puķīte: The idea of the greenhouse as a uniting concept for the Kogo Gallery stand came while thinking about the work of both artists, Mari-Leen Kiipli and Eike Eplik, and having conversations with them. Both are deeply fascinated by nature and its complicated relationship with humankind. Each of the artists is using their own point of view and visual expressions to analyse the arrogant state of the Anthropocene, and at the same time urging viewers to disconnect from it and reconnect with the biomass.

The greenhouse itself is a great metaphor for all the good and bad impacts humankind has had. It can represent an escapist fantasy garden and a place of care. At the same time, anyone interested in environmental issues will know how poisonous greenhouse gases are for the atmosphere. Paradoxically, this poetic symbol of care can easily become a symbol of human control and the overheating of the planet. In selecting Kiipli and Eplik to represent Kogo Gallery, we want to introduce artworks that underline the beauty, strength and healing qualities of nature, yet also point to the dualities of this world, where elements of nature can turn into poltergeists when provoked and start to haunt us.

Finally, the construction itself takes its inspiration both from previous installations by Kiipli as well as old garden districts in Estonia. Particularly relevant is the almost demolished Chinatown area in Tartu. These places, which serve as summer gardens for working class people living in tower apartment blocks, are slowly being taken over by developers, a sequence which, in the context of the current green community movement, seems regressive. For now, these communities are still there – with sheds and greenhouses creatively put together from found materials, just like the installations of Kiipli and Eplik, which are often built in several layers like eclectic birds’ nests.

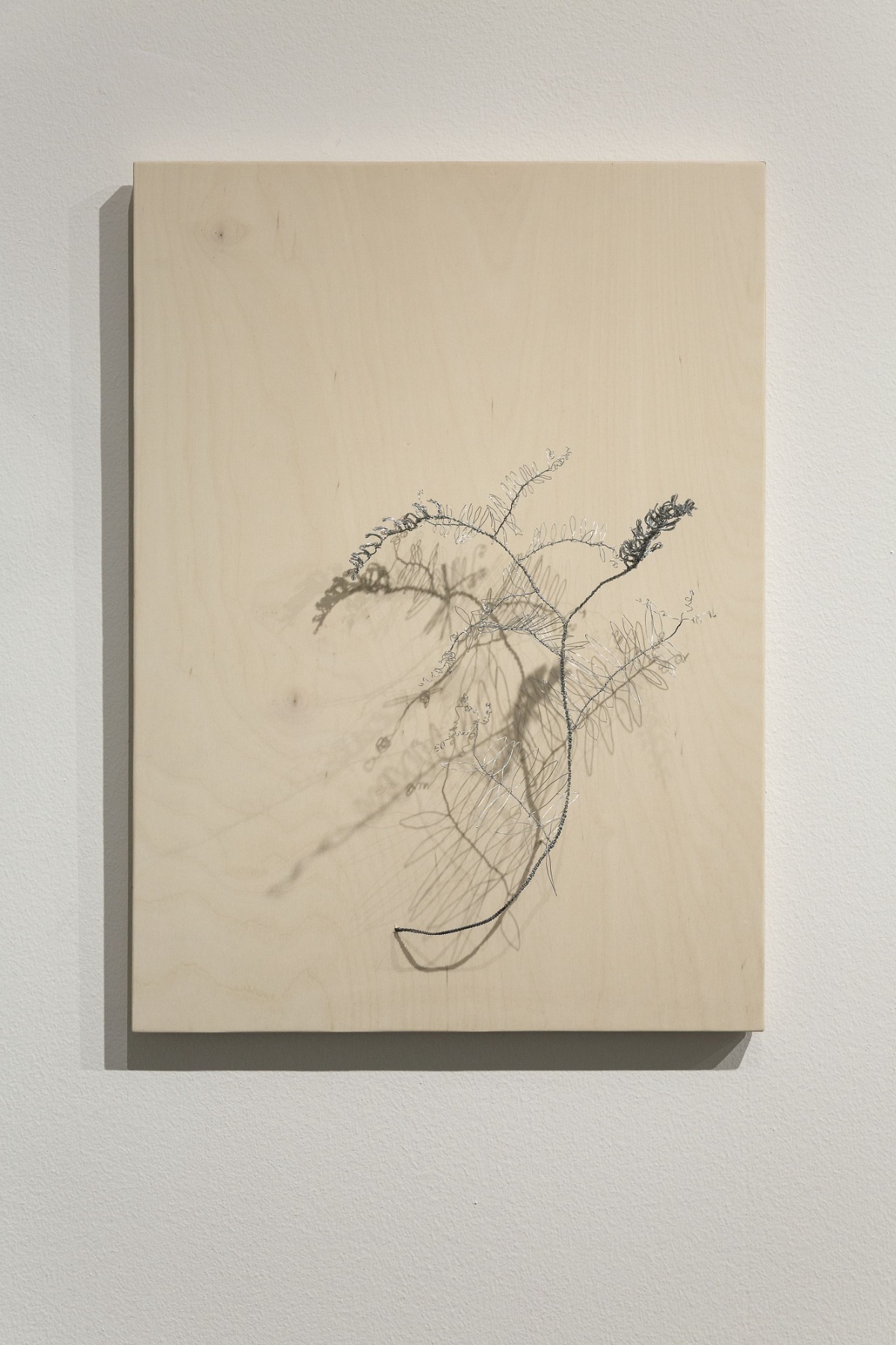

Mari-Leen Kiipli. Husa, Haapsalu City Gallery

Could you briefly describe the concept behind the upcoming exhibition for Liste Art Fair Basel? How are you working together?

Eike Eplik: It is a combination of different works inspired by nature. The different elements should complement and support each other, just like species in nature. In other words, we are creating our own small yet diverse island, the realness and naturalness of which is called into question by the greenhouse roof towering above.

Mari-Leen Kiipli: Yes, it is based on our works from different periods and so, perhaps on a shared interest in nature found in our practices. We use different tools to explore this interest, and while I have spent a long time working with video and exploring its possibilities in an exhibition context, Eike uses spatial materials. For this exhibition, we combine these works to create a new comprehensive environment.

Eike: And to answer the question of how we work together: most of the pieces we are showing at Liste have been made for previous exhibitions – we are not cooperating in making any new work. Since it was the curator who brought us together, it is more a question of how our concepts meet in the exhibition space and come together in the greenhouse. But I think we go together well in one space.

Mari-Leen Kiipli. Husa, Haapsalu City Gallery

How do you view your role as artists reflecting upon ecological issues and bringing these into the spotlight? What can an artist do that no one else can? Why is it important to take an active position?

Mari-Leen: Making art guides your thoughts, perhaps in a more intuitive way, and helps us see the connections between nature, society, and the personal-emotional. As an artist, I can convey an experience that the viewer has previously not had or has forgotten, and only personal experience can have a deeper impact.

Eike: An artist can express herself non-verbally, creating an environment, something that another person can experience and from which they can extract information or emotion. Visual art, and sculpture and installation especially, are perceptible through a multitude of senses, making it possible to see the physicality of things.

Through art, I can also, in my own gentle way, draw attention to important topics, such as ecological issues. I am not an activist-artist by nature, but the situation is already so bad that I can no longer stand in silence. If you care, you just need to speak out.

Eike Eplik. Hiding Place I, Tartu Art Museum, 2021. Photo by Hedi Jaansoo

How would you describe your personal relationship with plants?

Mari-Leen: I started working with nature because I like plants, flowers and beauty – the details of nature. It is also interesting that historically, it has been considered an art practice distinctive to women, as if flower paintings were a motif appropriate for women, while also being perceived as less valuable. To me, it is no less important than, for example, history painting.

I also enjoy the process of growing plants and seeing how a plant develops and what it needs. It is good to just look at plants in nature, too, not necessarily to study or identify them, but simply to observe and contemplate. For some reason, some plants are more appealing to me than others – there are some peculiarities that speak to me. It is the wonderful meadows full of crickets, thistle, St. John's wort and yarrow that I remember most vividly from my childhood.

Eike: I am also interested in beauty; I am not afraid of calling a thing beautiful. The concept of beauty has been shunned in contemporary art for a long time, which is almost funny in my opinion.

My relationship with plants is manifold. I find them highly appealing aesthetically. It is interesting to watch them, how they grow in nature, but I also have houseplants and cultivate plants for food in the countryside.

In Estonia, you get to observe the four seasons in all their variability. What would it all be like without plants? I was in the country over the weekend – violets and wood anemones are blooming in the forest undergrowth; you can still catch sight of some liverwort, bird cherries are starting to bud (the interview was done at the beginning of May – Ed.). If there were no plants – no bird cherries and jasmines to blossom, no strawberries to ripen, no birds to sing – then what kind of emotional and experiential effect would the seasons have on people? What would this world be like? I was there, surrounded by the singing of wild birds and all this flowering, and there were some bizarre beetles clambering about on the ground – they were bright blue, I had only seen pictures of them before. And then you think, what if there was none of this. Just an empty field and silence.

Plants are also medicines. Already as a child, I was taught to put a leaf of broadleaf plantain on a wound, and pick cowslip and mint for brewing tea.

I really admire plants. I find them marvellous; they are so versatile and exciting and well… yes, cunning.

Eike Eplik. Do You See Them As Well. White Clover - Trifolium repens, Tartu Art Museum, 2021. Photo by Hedi Jaansoo

Do you think it’s possible for a human to understand what it is to be a plant?

Mari-Leen: To start with, human beings should try understanding other humans, try being attentive and open. In time, doing this would also foster a sense of respect for other life forms.

Eike: I don't think it is possible to know what it feels like to be a plant. And is that even necessary? It is important, however, to recognise that being a plant is at least as important as being human.

No doubt plants perceive the world very differently from us.

Mari-Leen: We live in different times. Their time is somewhat slower, and although they give the impression of being static, they are really always active.

Eike Eplik. Do You See Them As Well. Tufted Vetch - Vicia cracca, Tartu Art Museum, 2021. Photo by Hedi Jaansoo

In her book Bodies of Water. Post-human Feminist Phenomenology, Astrida Neimanis writes: “I hoped to explore the ways that how we know the world directly relates to how we act in the world. So, how we know water, and what we think water is, directly influences how we treat water. If we think of water as a commodifiable resource, if we think of water as something out there, if we think of water scarcity or water contamination as something that happens to certain communities, this will affect the way we treat water in our quotidian, everyday existences. Water isn’t something out there, it’s us. How we treat it is how we’re treating ourselves, our kin, our more-than-human kin.”

Her ideas come very close to your own. Do you see how we could return to this interconnectedness, to a direct contact with everything?

Mari-Leen: Maybe the environment is already present in us and finds expression through us. In a more negative sense, we experience it with toxic chemicals from industrial residues that reach our bodies and start changing them. It happens either way, no matter whether we are conscious of it or not, but a broader regard for this issue could lead to better and healthier solutions. Ideally, this intertwining on so many levels could be mutually supportive and empowering.

Eike: Our attitudes and mentality should change. People should start viewing themselves and the world differently, perceiving themselves as one part of the ecosystem.

At the same time, we have great masses living in vast cities, and their relationship with nature is already next to none. How could this understanding come about? And poverty, which is very common in the world... How to approach someone whose basic needs are not being met? There are big decisions that ought to be made on the political level.

Eike Eplik. Do You See Them As Well. Tufted Vetch - Vicia cracca, Fragment. Tartu Art Museum, 2021. Photo by Hedi Jaansoo

Mari-Leen: The economic pressure on nature is immense, and decisions that have direct implications for nature in Estonia are especially painful. For example, the policy for renewable energy subsidies that classifies biomass as renewable energy and supports logging activities as a result. In a broader sense, it is possible that a system of reservation areas alone would not be enough, since environmental degradation is a global problem that cannot be solved within a single country. It is likely that we should be thinking of non-destructive ways for human activity to coexist with the natural environment.

Eike: Big decisions should also be made at the individual level. One possible key is to give some things up. People want to both save the world and keep on living in exactly the same way as before. In fact, we should radically change all our consumption habits. Why not back up a few steps?

Eike Eplik. Do You See Them As Well. Field Horsetail - Equisetum arvense, Tartu Art Museum, 2021. Photo by Hedi Jaansoo

Eike Eplik. Do You See Them As Well. Field Horsetail - Equisetum arvense, Fragment. Tartu Art Museum, 2021. Photo by Hedi Jaansoo

Je suis biomasse, “I am biomass”. Why is it so difficult for us humans to accept this?

Eike: Humans have long shaped nature for themselves, and it would seem that we are more concerned about belonging to a world of our own creation.

The average person sees the natural environment as a background, something lower or less important. A large part of humanity lives in an artificial environment; our connection with nature is no longer acknowledged – it seems somehow distant, dangerous, maybe even dirty. Organic processes are obviously scary – who wants to imagine themselves rotting like a pumpkin?

It has to do with the fear of death, which is compounded by the fact that different generations no longer share living spaces. Few get to intimately see another person age and journey towards death. People do not want to see it, and so we have created a world where some inconveniences are easy to avoid. But nature constantly shows you that nothing is forever. And yet the cycle of life continues eternally – all matter is in circulation, transforming from one thing to another. Human beings do not want to acknowledge their own mortality – to acknowledge that we are biomass.

Not many people like to think that we are still animals.

Eike Eplik. Ghost in the Corner: Bud, Kogo gallery, 2020. Photo by Marje Eelma

Is there any way we can build a new human, a new thinking, a new philosophy out of this metaphorical greenhouse or gigantic wastebasket we are living in now?

Eike: With good will, anything is possible.

What the pandemic has brought home to people is that we can’t go back to the way things were. In the meantime, we don’t have very clear alternatives for how to move on. The key word of our time is “uncertainty”. What kind of culture could emerge from this notion of uncertainty?

Mari-Leen: Some of the shortfalls in society have started to receive more attention, which is in itself good. There are attempts to establish social benefits, and even the issue of a universal basic income has been raised; there has been more talk on the issue of domestic violence as well as the environmental impact of consumption and travel. This kind of uncertainty or concern is welcome.

It seems to me that people are thinking more and more broadly these days. This kind of awareness should be here to stay.

Eike: It is rare indeed that people all over the world have shared the same experience. There is this new kind of sensitivity or receptiveness. But I don't know if this will bring on a more substantial change. When not sure, people usually proceed forward.

Maybe it is the curse of humanity, a feature of our species – a desire to always get and achieve more. I am an artist and want to publish a book. But this means contributing to bringing more stuff into the world... And so, is it worth doing? This constant striving is so inherent to humanity; it seems like curbing this would take a great deal of effort. On the one hand, this creative driving force and will is a good thing; on the other hand, it often goes too far. The element of restraint needs more cultivating, more attention. It is not just about going forward, but about how we go forward.

Questions by Una Meistere / Interview and editing by Karin Kahre, Kogo Gallery / Translation by Lea Soorsk for Refiner Translations

Title image: Mari-Leen Kiipli. Husa, Haapsalu City Gallery