I think art is a healer

A conversation with artist Paloma Tendero

Paloma Tendero is a young artist from Spain who works across photography and sculpture, combining both media for a better understanding of body and inheritance. She is currently living and working in London and actively participating in different international projects. She finished her BA in Madrid, focussing mostly on sculpture, and received her MA in Photography in London in 2011. Her work is part of the Hyman Collection of British Photography and is currently being shown in the group exhibition A Picture of Health at the Arnolfini Contemporary Arts Centre in Bristol. Paloma has taken part in many group exhibitions, forums, and other collaborations as well as artist residencies such as Sarabande (The Alexander McQueen Foundation in London, 2019-2020) and KulturKontak AIR (Vienna, 2018).

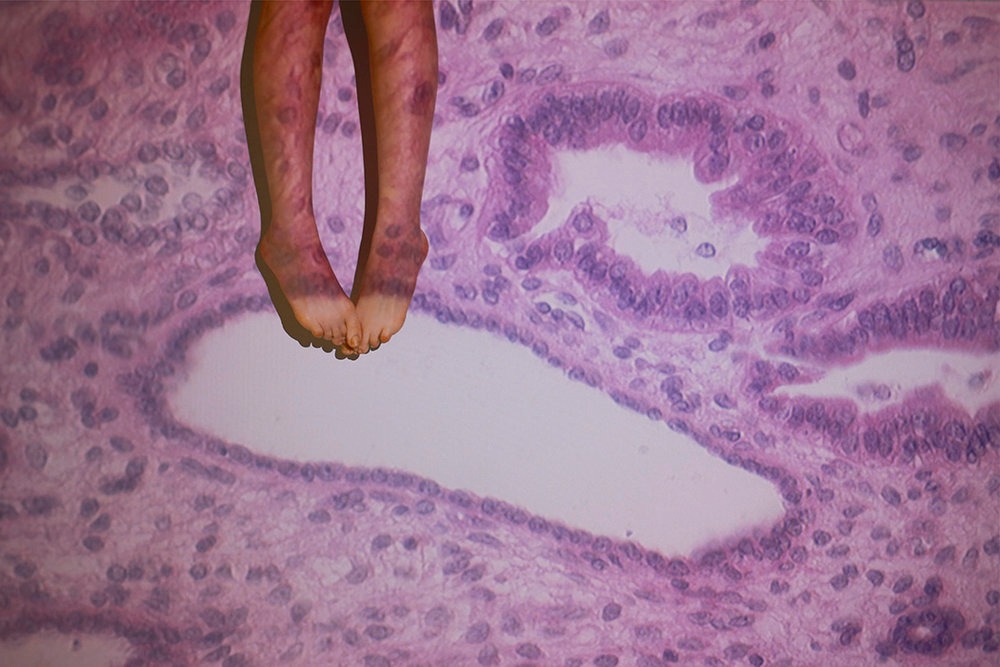

It was at one such gathering that I first had the pleasure of meeting Paloma and experiencing her artwork. In 2016 she visited Latvia to take part in the summer school “Error?!” at the Rucka Artist Residency in Cēsis, organised by the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art (LCCA). At the summer school, Paloma presented her work Inside Out, which problematised the question of error in many ways. It took the concept of error in a broader sense – not only in regards to knowledge, facts and perception, but it also questioned errors that were not created by humans and that are not (as yet) solvable. Moreover, it also questioned my perception of beauty in art and in the world as such: Inside Out taught me to see the beauty in errors that occur in human bodies as well as because of illness.

Paloma's art deals with the tension between biological determinism and free will by questioning the perception of the human body, normality, and illness as well as inheritance. Using both sculpture and photography, she seems to play with temporality – with the fragile existence of bodies and things and their more or less eternal (or long-lasting) counterparts such as representations. Her work is very personal as it is her body that serves as a material in her work and her history that forms the content. However, it reaches out to others as well, questioning the general relationship between one body and another, and between genetically, socially, or economically connected bodies, which in the end become one despite their differences. Paloma's work is visually expressive. It doesn't create alternative forms or copies of what is thought to be ugly and bad in a body – she takes it as it is. On the other hand, she succeeds in creating something new – a new way to treat questions of illnesses that are inherited and unchangeable. She creates freedom from this biological determinism by questioning it and getting to know it.

It appears that despite the pandemic and the overall closure of the world, her creative work and active collaborations won't come to an end or close up any time soon. Exactly the opposite is happening, I'd say. On the day we meet to talk, she has already had five portfolio reviews and presentations for different photography projects and art fairs. However, she doesn't seem tired at all; in fact, she is energetic, powerful, and ready to accept all the challenges that may come her way.

Paloma Tendero. Inside Out

Why do you work in such different kinds of media? You have been doing photography and sculpture for a while now, but now you are doing performance as well.

I received my BA in Fine Art in Madrid and I mostly did sculpture – so my background is actually sculpture. Then I came to England to do an MA in photography. So that’s when I started combing photography and sculpture – working in both media. The performative aspect came later. I didn’t realise that I was doing performative work because I do the sculptural objects by myself and take the photographs by myself or with some help from assistants. But at the same time, my work is very organic and it flows from one medium into the other, so in some projects this flow and combination – the process – is important. I have never done proper performance. Usually, the final work is a photo or a sculpture; I haven’t done video art. I’m not sure it is my thing.

Paloma Tendero. Inside Out

But what about embodiment? A very prominent theme in your work is the lived body. Do you experience the creation of an artwork as a bodily experience? As a sort of performance for yourself?

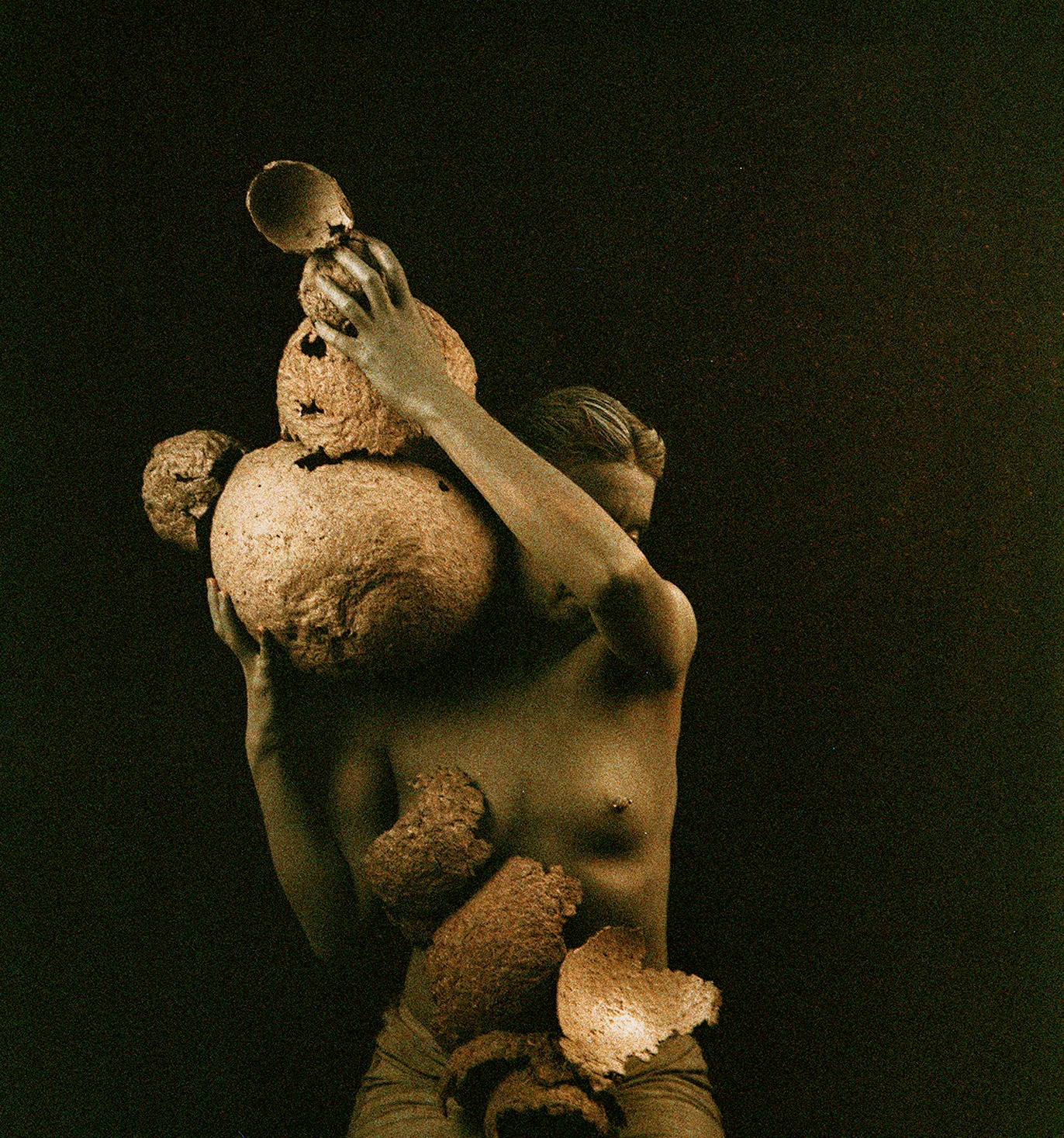

I guess there is a performative aspect. It is a very cathartic kind of expression. If I have an emotion that I want to explain in my art, then I have to create a performance for myself to actually feel relief afterwards. Maybe it’s a funny way of working. But I do question the functions of my body and the lack of control I have over it, and the process of interaction with objects that sometimes don’t really exist. I don’t photograph the things that are there in our everyday life. I create the things that don’t have a place in reality. I use art to create spaces for conversations with objects that don’t have any space by themselves.

Paloma Tendero. Inside Out

Speaking of conversations feels very personal. However, it is not just an inquiry into your own body nor into bodies in general. Inheritance is also a topic you engage with in your artworks. Do you feel like you somehow connect with the people that are connected to, or form, the content of your work? Maybe these are not only conversations with nonexistent objects but also with existent ones.

Yes, Through Myself is one of the first works I did when I was finishing my BA in Fine Art. It is about exploring where I come from. I wanted to speak about how you can see yourself in your family. I am very like my mother, so in this work my mother and I were playing with frames and how you can see a relative in you. My mother and I share a genetic disorder – I have chronic kidney disease. In some works, I included the genetic view of what my mother and I share.

My mother passed away because of the illness. I’m still here. For me, making Inside Out was a way of connecting with my ancestors. Even though now, looking back, I see my body more like a material – a container that contains my organs, lived experience, memories and genetic information. That’s where this conflict between biological determinism and freedom comes from. I don’t want to deny my family-line – I love my family and want to be a part of it. But you don’t get to choose which genes are going to get passed on. Having a genetic mutation sort of makes you question and see that you don’t have full control over your own body. I guess that is the part that drives me in creating art.

Paloma Tendero. Inside Out

Is art then an escape from this determinism? Do you feel that the creation of an artwork is really an act of free will by which you can overcome bodily and physical obstacles, and maybe even determinism, in a way? Does making art prove to you that your subjectivity is still the one that is in control, and not your inherited physical appearance or genetic information?

Yes, well, that’s something I have noticed working the way I do – that I don’t have control over my body, but I do have control over my art. When questioning one’s own genetic disorders, one inevitably comes to biological determinism. There is something very free in making art. I guess it is a way of overcoming that lack of control.

But you’re taking part in projects and planning the process of creation. Where is the freedom in making art according to a project?

I guess, making the objects – the sculptures – is a very organic process. I just play with the material and with forms without putting much pressure on the result. I try to follow my instincts and what my body wants to make. I do it with bare hands and sometimes end up just doing repetitions. What I do plan are the photo sessions. If I do it on film, I need to know how much film I’ll need, and for digital photography there is also some planning involved. I don’t want to shoot thousands of pictures, therefore I create a planned setting.

For me, art is a privilege. I think if I were born in another part of the world, I wouldn’t have the privilege to be in my studio and work and make art. So, even though making art also has challenges, like controlling the medium and overcoming mistakes and failures, it still is true that I must be very lucky to be able to make art.

Paloma Tendero. PKD Studies

This relates to the question of identity. Do you feel like the artworks interfere with your identity? What about the relationship between artwork, your body, and you as a subject?

Sometimes I think that if I didn’t have this genetic disorder running in my family, I might not have come to art. There is also an aspect of timing. I think that because of this genetic condition, I’m more aware of the fragility of my body. I’m more aware of my mortality. And because of this awareness, I want to make the most out of my lived experience. And because my favourite thing to do is art, I became an artist.

I think it does have an impact. I have friends that have decided not to sacrifice their full-time jobs to be artists. They want the stability of having a full-time job. But I prefer having a part-time job and suffering a bit financially in order to do what I love, because I’m aware of the fact that I don’t know when my body is going to fail me.

Paloma Tendero. PKD Studies

Do you find some rescue from mortality in the artistic process? Would you agree to the statement that you can become immortal through your work?

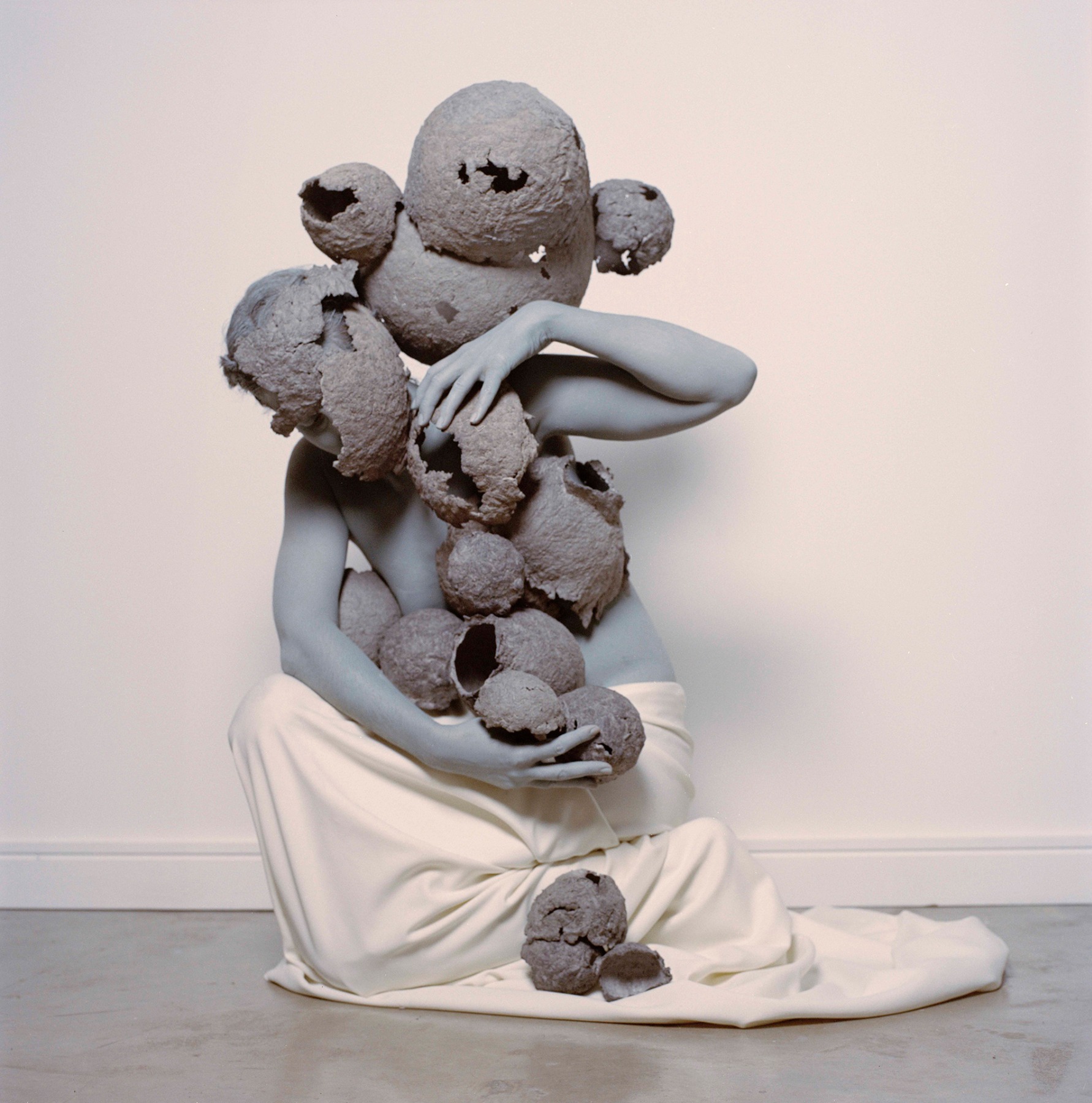

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about why I focus on sculpture, especially classical sculpture, so much. I think it might be because sculptures are timeless. They don’t include the perception of time as it is inherent in other media. Like, it preserves time. Maybe subconsciously, without realising it, that was what I was trying to do: preserve my body through my work.

Paloma Tendero. On Mutability

And in terms of photography?

I guess photography allows me to capture and preserve the moment. Maybe subconsciously, the realisation of how photography captures the time and captures the moment the way that sculpture cannot is what makes me combine the two media. In a way, photography preserves the moment as well, but then, over time, photographs can deteriorate. I guess I like the balance of both of them.

Paloma Tendero. On Mutability

Do you think that art can cure? And if so, who?

I think art is a healer and that there is an aspect in which art is therapeutic. It has properties that people can benefit from. But I guess I find that I don’t see myself as an art therapist. I think that to be an art therapist, you have to be trained in psychology even though you use art only as a medium. I don’t intend to be an art therapist, but I guess, in a way, art helps me, and I hope it helps the viewer too. I try to help the viewer by raising questions. And by raising the questions that form the themes of my work, I invite people to explore by themselves.

Paloma Tendero. On Mutability

Do you see an artwork more as a question or an answer?

I think I see it more like a question. The answer depends on who is looking.

For me, your work also raised the question of beauty and the representation of illness in art. Do you think that illness should be discussed in art? And in what way should it be done? Should illness be made visually pleasing?

I think art opens up space for conversations that would be awkward in many other environments. Illness is something that is not normalised, although with Covid-19 this is changing. We don’t speak about illness as we do about other topics: it is a sort of taboo in contemporary society. But artwork doesn’t have those boundaries; an artwork allows you to speak of subjects that are controversial. I think it is important to have this space of the art-world in which to speak of illness and other topics that are relevant but that don’t have space.

Regarding beauty, I was raised thinking that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. You don’t know what is beautiful to me, and I don’t know what is beautiful to you. However, I once had a class with a professor who told me that my pictures are too beautiful to talk about illness. I still don’t understand what he meant. For me, illness is intriguing. It is not about ugly or beautiful. It is about wanting to know more, wanting to know how it works, why is the body malfunctioning or functioning. There is something very intriguing about illness. And because of this, and also curiosity, it is beautiful.

I work with classical sculpture. Classical art as such has formed our cultural identity and the idea of a perfect body – that is something we have inherited. That’s why I try to work with contrasts and, as in Flawed Beauty, use, for example, cysts or objects that are considered ugly in beautiful ways and combinations.

Paloma Tendero. Flawed Beauty

It’s interesting how you speak of twofold determination: our thinking being influenced by the cultural background, and physical existence influenced by inheritance and genetic information. There seems to be hardly any place for freedom. Taking this all into consideration, I want to ask: do you feel free, or is this freedom just in the art medium in which you can express yourself freely?

I feel free in the sense that I’m a free person and I can make free choices. For example, I chose to be an artist. I also have freedom of thinking certain thoughts. I don’t have the freedom of mind, but there is some freedom. For example, in the work On Mutability, I spoke about fertility. I created all these eggs, and by balancing the eggs on the columns, I was asking “Would you bring life into this world if you knew that you will pass on genes that might be compromised with a genetic illness?” I guess people who don’t have such a story as mine don't think about questions like that. There is a certain aspect of my mind that can’t become truly free, because I always have to consider this. It’s a part of my body. But I guess others have different things they have to constantly think about, for example, money, so I guess no one is really entirely free.

Paloma Tendero. On Mutability

And so after several years of work, have you found your own body? Have you found any answers to your questions?

I don’t know, really. I guess I’ve found an understanding of what I’m doing. I think I’m more in control and more aware of what it is that I’m doing. It took me several years. After graduating from art school, you’re still not ready to position yourself as an artist. Now I have a greater understanding of where I am and how to position myself. I guess that is something I have found out.

Paloma Tendero. On Mutability

I can imagine positioning being a difficult task. However, as your work is mostly bound to your own body, I was wondering if maybe you have achieved some super-human ability to control your body?

I think I’m more aware of my own body and emotions; I can identify things better. But at the same time, I don’t want to be in control and thinking about it all the time. I think it really is about the balance of how much you learn. Knowledge is important, but it shouldn’t be made the centre of one’s life. One should have a healthy understanding of one’s body, though.

Do you think that a lack of knowledge might also be important for an artist? Earlier we spoke about curiosity and intrigue, and you mentioned it as the driving force of your work. Would it be lost if we knew everything?

Absolutely. I think if I didn’t have this curiosity, or if I had all the answers – what could I question? That’s why I also thought that, for me, an artwork is a question. There are no answers in realising that you have a lack of control over your body, or that you don’t really understand your body. The unknown is definitely a big part.

Paloma Tendero. On Mutability

Would you like to get these answers?

I don’t know. Maybe if it happens naturally, because of different processes in my life. I have to say, when I look at my work from years ago, I see it with different eyes. Some answers come very naturally to me – of course, it was this I was thinking about and that is the answer I got. But there are so many questions in life that I can’t even formulate all of them.

Have you looked into scientific research? I must say your work is quite scientific, so you must have some understanding and knowledge about biology or genetics, at least.

I have used science to support my ideas – to have a picture of what is a genetic mutation and why the genes break, and how it happens, etc. But still, it is such a fascinating subject that I don’t really understand it even though I have read scientific literature on it.

Paloma Tendero. On Mutability

A tangential question: I saw that you took part in a feminist art project. This got me thinking – how do you experience your body? As the material of your work, do you still connect it to gender or sex?

The role of an artist is to explore and to give voice to contemporary topics. It must reflect the world we live in now. Women of the world, women artists – that is a real topic. As the world evolves, the representation of females and womanhood are topics that we have to speak about. I think if I were a man, I’m not sure if I’d still work with my body in the same way. But I’m not. What I want to say is that in my work, I want to see my body as an “un-gendered” body. However, because I’m a woman, gender and overcoming it becomes a really important and deliberate part of my work.

For me, the experience of your work was always a very anti-gender experience. Of course, the sex was still prominent because you create nudes. But it seemed like the message was human, not feminine or masculine. It seemed like you got a hold of the body as it is, although your work is very personal. In what direction are you planning to move this inquiry in the body through art?

I’m a woman, so there’s not much more I can do in terms of that. Although I’m thinking of photographing other people too. I’d like to give it a go. I’d like to photograph men to get a more general view of the body as such.

One other thing I want to explore is working with medical archives; to gain inspiration from them and see how I can work with them. But I also want to photograph other people and try to translate and combine their stories with my own thoughts. And to get to know all the possibilities this has to offer.

Paloma Tendero. On Mutability