Exploring the Museum’s Images – Exploring My Image. Group art psychotherapy in museum

An interview with Elisabeth Ioannides, education curator and art psychotherapist at the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens

Elisabeth Ioannides is an Education Curator and Art Psychotherapist at the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens (EMST). With its collection of Greek and international contemporary art saturated with existential and socio-political issues, EMST has all the potential to become a dynamic social institute that is edging closer to the new definition of a modern museum (which, unfortunately, is still in contention). Yet before the most appropriate definition has been decided upon in the backrooms of museum foundations, EMST, together with a number of other western museums, is already taking bold steps towards a new kind of museum – one that develops alongside and in interaction with the society in which it exists. Preferably, a united and mentally fit society.

At the same time, in order to bring EMST’s collection to the attention of the broadest possible audience as well as acting in the public’s interest, the museum's Learning Department has implemented a comprehensive and inclusive educational programme for people from different social and demographic contexts. The programme also integrates art psychotherapy museum groupwork, the feasibility of which is largely thanks to the efforts of Elisabeth Ioannides.

Having received her bachelor’s degree in Psychology and Fine Arts from Brandeis University (Waltham, MA, USA) and a master’s degree in Art History from the Courtauld Institute of Art (London, UK), followed by a post-graduate degree in Contemporary Art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art (London, UK), Elisabeth Ioannides has returned to her home country of Greece and joined EMST as an assistant curator. During these seven years of full-time studies, Elisabeth dreamed that she could combine her future work in the art world with psychotherapy. Unfortunately, upon her return to Athens, this dream had to be put aside for a while. However, in 2009 she learned about the Art & Psychotherapy Center (A.P.C) in Athens, which provided a certificate equivalent to a master's degree and recognised by the European Psychotherapeutic Association (EAP). She enrolled and submitted her dissertation on the application of art therapy in museums. In 2016, she made a proposal to the director at that time - Katerina Koskina, who passed it through the Administrative Board. So, in 2017, despite the permanent collection not being on view, Elisabeth Ioannides established the first pilot group, composed of ten individuals, which met for three months (twelve two-hour weekly sessions). In synergy with the First Department of Psychiatry at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and Eginition Hospital, the museum has created and strengthened its art psychotherapy programme titled Exploring the Museum’s Images – Exploring My Image. As the title of the programme indicates, it is an opportunity to give a visual voice to one’s inner world through finding inspiration in the museum's collection.

Elisabeth Ioannides

Alongside the artworks in the museum's collection that reveal that human beings are not alone in this world – painful experiences are common to all humanity – in the following conversation Ioannides also highlights the trust, sense of community, and ability to speak through each other that is realized in the museum's art therapy groups. Ioannides also touches upon the potential of museums to become role models in various social integration processes.

As an introduction, could you describe the differences between classic art therapy and the group art therapy being done by museums?

The biggest differences between classic art therapy and group art psychotherapy in the museum is that the artwork that is exhibited in the museum comes into play, and that the therapeutic sessions take place in a non-traditional setting. In general, art therapists use the visual arts to psychotherapeutically help their clients deal with different kinds of issues. In a classic art therapy session, the patient has a discussion with the therapist, then the patient creates an artwork (or not) after which both discuss this creation and the process. Whereas here at EMST, in the therapy sessions I hold together with my colleague, we have already chosen artworks that, from our perspective, we think would resonate and bring out issues that could be addressed. For example, motherhood, gender, sexuality, issues of isolation, abandonment, distancing, etc. We focus on one artwork each time. Other times, we might leave group members alone to choose an artwork by themselves. They find artworks that resonate with them, then they take notes (thoughts and feelings, words that come into their mind) and then they go back to the art workshop to create their own works. So, what we discuss is their artworks, their creations, and what resonated with them from the experience within the galleries – that is what we explore in the psychotherapeutic sessions.

Another thing that is very important in therapy sessions is how the participants go about their creating, and not only about the things they say verbally. For the art therapist, it is very important to look at the process. For example, for one person it may be easier to make a collage rather than paint – they prefer to work with already existing images; in this case, it is important how they combine the images and what they say about them. Recently, we had a cancer patient who unknowingly used a “STOP” sign from a magazine. She just thought it was interesting, but the statement that she had made using that big red sign was very meaningful!

Is there anything that differentiates the art therapy programme at EMST from those at other museums around the world?

Compared to the other programmes that we are aware of, ours differs in that we don't hold sessions for particular populations, i.e. we don't have one programme for cancer patients and another one for Alzheimer patients or for people with eating disorders – we hold sessions for the general public. We put out an open call on our social media and our website; every interested person above 18 years old can apply. Then we hold a series of interviews to see what their aims are, what are they thinking, what their issues are, if they can do group therapy, if they will be committed to it, etc. For example, if a person who applies cannot commit to the group, we probably won’t introduce them to the group. We want a cohesive group that can move through the stages together because it is a short-term therapeutic intervention, not a long-term. And we don't want to break up a group.

VIDEO: EMST for all. An exhibition from museum's Department of Education (28.02.-04.10.2020)

Could you elaborate on the significance of the group in museum art psychotherapy?

It is important to observe, listen and understand as a group. Because a lot of the work that is done is done by the actual members of the group. You know, there are as many personality characteristics as there are people. For example, you might have people who don’t want to speak up a lot and who don’t open up very easily, but they do have things inside of them and someone else from the group might become their voice. By saying this, I mean somebody’s point of view may also reflect something that another person in the group is feeling as well. Many times in group therapy when a person starts speaking about themselves, another person who is sitting across from them feels exactly the same way. So that person is, in a way, talking through the other one. The group dynamic is very important because it raises the group’s issues. Of course, there can be opposites – some people may get angry, some may get upset, but what is important is the way they behave in the group. Because it shows the way they behave in society at large. If we have a conflict in the group, we try to raise awareness of what is happening and explore why participants could be acting this way, so that they can take this outside into the world – in the way they interact with their family members, friends, and overall.

Many times in group therapy when a person starts speaking about themselves, another person who is sitting across from them feels exactly the same way.

You mentioned that in the therapy sessions you work together with your colleague. So, there is more than one professional involved in each session?

Yes. I am an education curator and I am a trained art psychotherapist, but I don’t do the sessions alone – Aphrodite Pantagoutsou is with me. She is a psychiatric occupational therapist and art psychotherapist at Eginition Hospital. Therapeutically, it is interesting because we are like a parental couple. We have distinct, different roles – otherwise, the group could get confused. Synergies are very important when you try to hold group sessions like these. So, as an education curator I talk about the artists and the artworks – I try not to intervene psychotherapeutically as much as Mrs Pantagoutsou has a more psychotherapeutic role. However, after the session ends, we always analyze the process and the issues that were raised – together, as a team.

EMST had been under renovation for several years, and when you started the first therapy pilot sessions, the permanent collection of contemporary art was not yet accessible to visitors. Then came the Covid-19 restrictions. Consequently, availability and access to artworks has been limited throughout this time, and you have had to show the selected artworks on a computer – on a video screen. Participants were not in contact with the actual work. How does that affect the perception of the work and, ultimately, the quality of the therapy?

In museum art therapy, just being in the museum – the architecture of the museum itself, the space, the sounds, the lightning – can create a lot of feelings for an individual. The building, as well as the artworks, can affect the session and the individual. Especially when it comes to contemporary art – we have a lot of videos, a lot of installations which you have to walk around or inside them. For example, we show “The Boat of My Life” by Ilya Kabakov, one of the most important works of conceptual art; it is an artwork that you have to walk on it in order to experience it fully. It is completely different if you only see images of it. Of course, being in contact with the actual artworks is very important and changes a person’s perception.

In museum art therapy, just being in the museum – the architecture of the museum itself, the space, the sounds, the lightning – can create a lot of feelings for an individual.

Exactly. Even a face covering sometimes prevents you from fully enjoying a museum visit, an experience that engages many senses. A work of art even has its own aroma, such as a fresh oil painting or an installation made of natural materials, etc. I also suppose that online encounters, or even face-to-face meetings but with face masks being worn, can affect the therapist’s ability to observe patients’ behaviour and reactions.

Yes. When we first introduced ourselves, we asked everyone to take off their masks in order to see what the other person was like, because it is not easy to see another person nor his/her expression with a mask. The same holds for doing sessions online, where you only get a partial image of the person.

However, even keeping at a distance is something to be explored by a therapist. In our first and second groups, we usually made a close circle in order to discuss; in our third group which was held during the pandemic, our circle had to be much bigger. Everything comes into play in therapy. It might be taking place in the museum and we might be talking about artworks, but life is there! And as an art therapist, you take into consideration everything!

Everything comes into play in therapy. It might be taking place in the museum and we might be talking about artworks, but life is there!

I would like to talk about the healing power of art, especially contemporary art. With its sometimes provocative, sometimes commercial nature, with all its concepts, etc. – is it really a suitable environment for self-exploring, for self-discovery, for healing?

We have to understand that art therapy is about the process of looking at something and about the way it resonates within a person. For example, we have a refugee tent – a work by Palestinian artist Emily Jacir – about all the villages that were occupied and depopulated by Israel in 1948. It is about the experience behind it and, yes, you need to hear about this experience for the work to resonate. Yes, it is a UN tent, but maybe you had an experience with a tent in your childhood when you went camping with your parents. The connections that you make, all these connections that go on in your mind – it doesn’t have to do with the villages that were destroyed in Israel. It is the experience you get. Connection, through artwork, to your personal experience. That is a whole journey that later leads you to create your own work of art and how you connect to that. In many artworks, you can find something that you can reflect on and connect to.

What is your most amazing therapy session experience of how an artwork can provoke a particular behaviour or reaction?

My “wow” moments in sessions don’t come from how the image impacts; they come from the actual interactions within sessions, from discussions, how one person views the other and what they realize about themselves. My “wow” moment is about the participants’ interaction with themselves and their realization about themselves, not the artwork.

Is there any reason to believe that art therapy in a museum is more effective than traditional art therapy?

I will not use the word “more”; I will use the word “different”. It is a different approach. It is not for everyone. Actually, in general, art therapy might not appeal to everyone. Some people prefer regular psychotherapy sessions, other people prefer music therapy or drama therapy. It is just a different means of approaching something, and it is one that opens people up.

It is important to provide a sense of security in therapy. Can a museum, as an open public space, provide this feeling to participants?

Yes, it is important in art therapy sessions to provide a safe environment for the participants. An environment where they know that whatever is said stays in the group. So, what do we do when we hold the session in a museum? After looking at the art on display, we go to an art-workshop, which is a small and contained room in which the discussions and creative process take place. It has a glass wall but it has blinds and the door is closed, so nobody can look inside to see what’s happening; nobody can listen in. We have a cabinet where we keep all the materials that are used in the therapy sessions because we don’t want them to be used by school groups or others. After the session finishes, we keep the artworks in the museum in a contained and closed folder. Nobody has access to it, but every participant gets their artwork back at the end of the whole group session. If the person doesn’t show up at the last session or doesn’t want, we keep their artwork for two years and then we dispose of it.

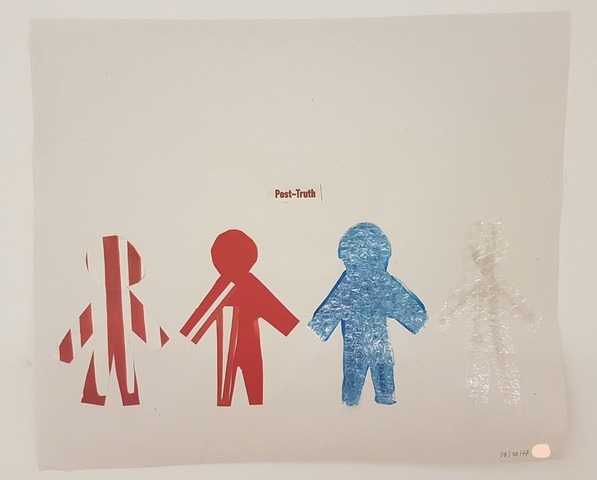

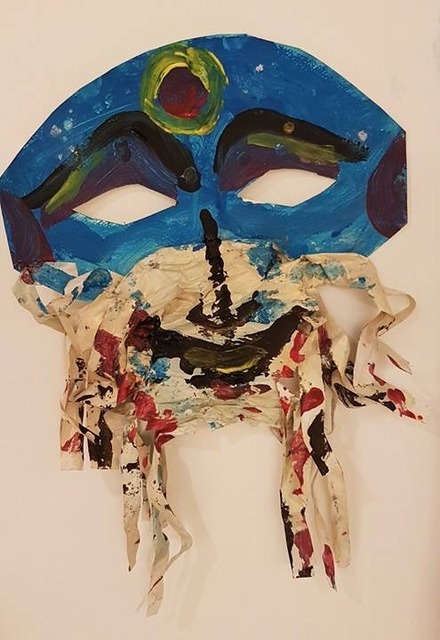

Another aspect of museum art therapy is whether or not participants want to exhibit their artworks. When we started our groups, our intention was not to exhibit the resultant artworks, but last year we held an exhibition of our educational programmes and we thought that it was very important to showcase the work that we were doing in art psychotherapy. We approached the participants of our previous groups and asked for permission to exhibit their work anonymously. Of 19 participants, eight or nine agreed.

This year in October, my colleague art psychotherapist Maria Konti is going to hold a workshop for professional art therapists. With the collaboration of other professionals (artists, psychiatrists, etc.) she is going to carry out workshops on how art therapists can work with archives. The very same way contemporary artists work with archives. Next year, in October, we are going to hold a symposium in which we will present the findings of this project.

How large/important is the contribution of museums to the general field of art psychotherapy research?

Well, at EMST, we don’t have quantitative measurements; we have only a qualitative approach on how the perspective of participants has changed or has been affected through the process.

Nowadays, the intersection of the arts, humanities and health is something that is developing consistently, and it is very important. This whole idea of responsive and caring museums is important. Museums have to be open and they have to integrate different fields in order to move ahead. For this reason, synergies are very important not only for museums – it’s how we can make all culture move forward.

Recently, I did a lot of research and we collaborated with the organization “The Happy Act” to make the museum autism-friendly. One of their prerequisites on how this could be fulfilled is that we need to train the staff to be welcoming to individuals on the autism spectrum.

The way we train the staff to welcome people with autism or other neurodivergences is important in how they will behave as individuals outside in the world.

Museums have to be open and they have to integrate different fields in order to move ahead.

In this sense, the museum has the opportunity to become a role model.

Nowadays, because museums worldwide want to increase their popularity, want to increase their income, or for other reasons, there is a lot happening. I’m not in favour of quantity but of quality. It is better to do less but plan it carefully, consider the impact, organize it, etc. rather than do a lot.

What do you think happens to a person on an emotional level when they cross the threshold of an art museum?

Individuals in the museum are provided with opportunities for participation, purposeful and active engagement, learning, entertainment. Their wellbeing can be enhanced and their health improved. They get out of their house, they do something different. Being in the museum can be a sharing experience and their whole view of the world can change. People start observing differently. A visit to the museum allows one to explore society and the environment on a different level – I don’t mean therapeutically.

And that’s why it is very important to involve all members of society in this process.