Art is generative of new kinds of realities

An interview with American artist and philosopher Megan Craig

American artist Megan Craig has three main identities, which are in constant interaction with each other: artist, philosopher and mother of two children. She is an associate professor of philosophy at Stony Brook University, where she teaches courses in aesthetics, phenomenology, and 20th-century continental philosophy. Her research interests include colour, synesthesia, autism, psychoanalysis and embodiment. Craig is the author of Levinas and James: Toward a Pragmatic Phenomenology (Indiana University Press, 2009) and is currently at work on a book about Levinas, Derrida and palliative care in America.

Craig began her career as a painter and now also works in the genres of performance art and installation. In addition, she is a graphic designer with Firehouse 12 Records. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, and she has been awarded painting residencies and grants from several institutions, including the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, the Weir Farm Trust, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, the Vermont Studio Center and the New York Arts Foundation.

In 2020, The New York Times published Craig’s essay “The Courage to Be Alone”, a contemplation – through the eyes of an adult and a child – about the new reality and our existence within it that was inspired by a walk with her younger daughter during the pandemic. “I try to recall something the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas wrote in an essay after the Holocaust,” she wrote, “something about how difficult it would be to teach children born after the war the lessons they would need, and especially, the strength required to survive in isolation. I would like to hold that text and read it again. It was written in French but called ‘Nameless’ in the English translation.

“We are cresting a small hill and my daughter suddenly sits down. She is hungry and tired and doesn’t want to walk anymore. I sit beside her, still wondering about what Levinas said. It was something about the courage required to be alone, about a fragile consciousness, and the importance of the inner life. Yes, that was it. The lanterns shining under the coats of those young boys, the rocks in our pockets, the inner life that cannot be seen or guessed or known from the outside and that therefore cannot be so easily extinguished or taken away. The inner life that kept Levinas alive after being captured by the Nazis and sent to a prison camp in France in 1940, separated from his wife and daughter, apart from the world. Something secret to hold on to that cannot perish or crack or fall, something private and still at the core of a life.”

We talked about the aesthetic and mental dimensions of art, about memories and traumas, about noise and silence. About art as self-therapy, as a way to learn about and understand the world, as a generator of new realities and experience, as a connecting element (for people, the environment, ideas, impulses), as the provoker of intellectual discourse, and as a kind of emotional balancer at times when such an anchor is needed.

“I think art is healing,” says Craig. “The making of art attests to a certain kind of plasticity. Whether it’s the plasticity of the brain or the plasticity of matter, it attests to there still being the possibility of making new connections, of remaking things, of experiencing failure that’s not final.”

Megan Craig, Rose Sings (installation shot), 2015, Kunstverein Grafschaft Bentheim, Germany / Photo: Helmut Claus

Philosopher Susanne Katherina Langer once said: “The function of art is to acquaint the beholder with something he has not known before.” From your perspective as an artist and philosopher, what is the role of art in our lives? In our everyday existence?

I love that you started with Suzanne Langer, who is such an important pioneering woman in American philosophy. I love her work. But the way I think about the role of art is maybe a little bit less in terms of cognition and knowledge than the quote by Langer might suggest. In a way, I’m more interested in experiences of mystery or incompletion, or fragmentation, and experiences that don’t fit neatly into ready-made categories. So, rather than think of art as a kind of new mode of knowing, I prefer to think about the way that art is generative of new kinds of realities and expands the possibility for what we count as experience. That includes new possibilities for emotion and communication and ways of occupying space together, being connected together.

I’m not so interested in the role of art in providing more knowledge but rather in disrupting the category of what it is to know. And making emphatic or intense things in life that otherwise would be unnoticed or just mundane.

In his work Formulations on the Two Principles of Mental Functioning (1911), Sigmund Freud famously wrote: “An artist is originally a man who turns away from reality because he cannot come to terms with the renunciation of instinctual satisfaction which it at first demands, and who allows his erotic and ambitious wishes full play in the life of phantasy. He finds the way back to reality, however, from this world of phantasy by making use of special gifts to mould his phantasies into truths of a new kind, which are valued by men as precious reflections of reality. Thus in a certain fashion he actually becomes the hero, the king, the creator, or the favourite he desired to be, without following the long round-about path of making real alterations in the external world. But he can only achieve this because other men feel the same dissatisfaction as he does with the renunciation demanded by reality, and because that dissatisfaction, which results from the replacement of the pleasure principle by the reality principle, is itself a part of reality.” What is your definition of artist?

There are so many things I really love about Freud, but I would say his conception of art and the artist is not one of them. Because I think it perpetuates the picture of a solitary, tortured, isolated artist who’s at odds with the world, and, at least for me, I feel like that’s the kind of model of the artist that’s entrenched in a really male, very narrow way of thinking about what it is to be an artist and what it is to be making work.

From the Freudian perspective, there’s trauma and then a flight from reality, and then art is the way you struggle your way back into reality through sublimation. Sometimes that’s the case. But I think that account predisposes us to looking at the history of art in terms of these tortured, heroic, often male, white figures. Reading into artists’ personalities with the idea that the more disturbed or distressed or non-communicative or asocial you are, the more artistic you are; I don’t think that’s accurate. And I don’t think it helps to make art more engaging and as open for people.

I think there are a lot of other pictures of practising artists who are very much engaged in reality, engaged in the world, and not in flight from the world. There’s an exhibition right now at the Met in New York City of portraits by Alice Neel. I think she’s such a wonderful example of this engagement. She went into her neighbourhoods, she went into the lives of other people in order to express them and show them in ways that they’d never been seen before. So that’s a very different gesture of the artist and of art than the one that wants to categorise the artist as privately suffering.

I don’t want to undervalue the pain and suffering and trauma in the life of any particular artist, but I think that historically we’ve also undervalued joy and curiosity and the way in which making art is an experience of genuine curiosity and openness to the world.

I think of artists as people who are driven by an endless curiosity to make and create. And that’s so different from any occupation in which you do your work and then you go home, or you finish a project and it feels final, it feels like it has actually had some kind of completion. I think of the artist as characterised by an incessant sense that there’s always more to do, that there’s more to make, that their work is an unfinished project.

Megan Craig, Shields (installation shot), 2018, Real Art Ways, Hartford, CT / Photo: Stephanie Anestis

You once said that you think of painting as very much alive. How does a painting do its work? What are the crucial aspects it adds to a domestic space? Why is it important to be surrounded by art in everyday life?

I used to be mostly involved in painting, but my practice has expanded into other media in recent years. But I think a lot about the material specificity of paint. You know, the material differences between the viscosity of oil paint, acrylic paint, watercolour and gouache and all the different speeds of these different mediums. I’ve always felt that painting is a negotiation with that specificity, and if you’re not willing to submit to the material life of the paint, then you’re constantly working against it in a way that’s just frustrating.

For me, the “liveliness” of painting is tied to that life of the material, which has its own will. I mean, it has its own relationship to gravity and to time and to pressure and to colour. Because I feel like the medium of paint is something that’s so alive and full of lively possibility, I’ve been drawn to painting more or less static objects, such as buildings and things that are considered inanimate objects, because I love the way that paint lends them life. There is a coming to life of what otherwise looks inanimate.

For me, the “liveliness” of painting is tied to that life of the material, which has its own will. I mean, it has its own relationship to gravity and to time and to pressure and to colour.

But I now use and think about other mediums as well, and this comes in part from my interest in the French philosopher Henri Bergson. He has this very beautiful description of all matter as just a difference in degree between consciousness asleep and consciousness fully awakened. I like to think about the way that art helps to awaken matter to some degree or another, and that the materiality and wakefulness or lightness of the material that you first use has certain potential for engendering different kinds of wakefulness going on from there.

And so, living with a painting, even after the painting dries, I think it takes on a kind of new life. I always love that moment when a work dries. Because it’s so slippery and in transit when you’re working on it, and then with oil paint you have to wait a few months for this moment to happen, but it finally sort of holds together, it gels together. But there’s an intimation that the innermost layer of that paint is still fluid. And I think that when you live with paintings around you, like in your home or in your space, that intimation that something’s still happening there stays alive. I think that even the most ancient paintings still have that.

Have you ever noticed or paid attention to how you think as an artist? Do you think in words or in colours? Or in forms?

Especially in relation to painting, I think it’s difficult to unhinge from thinking in words. At least for somebody who has acquired speech in a traditional way since childhood, that movement toward language gets to be all-consuming. So in painting I often think about different kinds of strategies for working in order to try to stall or short-circuit speech, because when you’re looking at something, the name tends to be in front of you so concretely, but you can’t paint the name. You have to arrive at the name; you have to not know what the name is.

I think it’s similar with writing, where it’s a question of finding new language. It’s like, whatever the language is that you have ready to hand, you also have to short-circuit or stall it in order to try to make your way into some new possibility with language. So yes, thinking in terms of form and rhythm and colour, I think there’s a whole repertoire of practices that you can try to engage in as an artist to sort of sabotage your linguistic brain a little bit.

Thinking in terms of form and rhythm and colour, I think there’s a whole repertoire of practices that you can try to engage in as an artist to sort of sabotage your linguistic brain a little bit.

What interests you in colour? Your website states that your research is focused on “accounts of memory, sensibility and the ethical importance of ambiguity – with a particular focus on sensation, synesthesia, colour and colour perception”.

I’ve done some writing and research on colour experience, and especially on the topic of synesthesia, in which there’s a crossover of the senses in which, for example, a person’s experience of a number is linked with a specific colour. There’s a whole range of different kinds of synesthesia. For me, first of all, it’s really interesting to teach the history of philosophy in terms of a history of thinking about colour, because it brings up so many issues about embodiment and also about the entrenched hierarchies of philosophical thinking.

By looking at colour, you arrive at all of these different problems but through a new lens. And it really does challenge the idea that names are adequate containers or holders for phenomena, because, you know, we may all understand the word “green” in a given language, but when we really try to get down to what we mean when we say “green”, there’s such a terrific range of what we understand by that term. It’s so contextually dependent on what the light is like and so on. So I feel that thinking about colour really helps to bring us into a more nuanced conversation about relationality and context and phenomena that are not distinct but are nevertheless so radically important for how we speak and feel about something. Even things like what you choose to wear, what the colour signifies, and what it signifies socially and historically.

For me, first of all, it’s really interesting to teach the history of philosophy in terms of a history of thinking about colour, because it brings up so many issues about embodiment and also about the entrenched hierarchies of philosophical thinking.

You’ve said in one of your previous interviews that it’s important to have a collection of objects about which you know that, whatever else may happen, they will still be there the next day. Do you think that art can act as a kind of emotional stabiliser in critical situations, providing emotional healing in some way?

I often think about two sides of this situation. For example, you go back to a museum to see the same work again and again over many, many years of your life. Or maybe you have a song or a bit of poetry or something that you recall and you can come back to. That seems to be a very common experience, having these things that are sort of like touchstones that provide some sense of persistence or comfort, some degree of healing.

But I also think that when somebody has a really traumatic experience, it’s exactly these same things that can sometimes feel like an affront; I mean, your whole world has changed, but that thing is still there, the same. Especially initially, I think that the experience of going back to, for example, the painting that you’ve always seen before and it’s still there with the same, you know, ridiculous smile on the same ridiculous face when everything in your world has crumbled, that’s sort of horrifying in some way. But I think that that’s a critical part of the process of coming to terms with the fact that your experience or your trauma is not all-consuming. It’s not, in fact, the entirety of the world that has crumbled. Initially, however, that can be a very painful realisation, because you actually want it to be the whole world that has crumbled. But ultimately, that’s a really important part of the transition out of the darkest places.

I do think that having that song or that verse – or it might be a prayer, or whatever – is a kind of lifeline that’s really important to have and to know that it will be ready, that it will be unchangeable and inert, in exactly those moments.

Do you personally have “that painting” or “that piece of music”, that need to return again and again to some particular space or thing?

I definitely do. The thing that comes to mind right away is, we lived in Belgium when I was a kid, and my parents had these posters of Bruegel paintings hanging on the wall. One of them was the Children’s Games painting, and the other one was Hunters in the Snow. And these kind of outrageous scenes, the tumble of bodies and the chaos of those paintings… Of course, part of it is that these paintings remind me of my childhood. But at the same time, I like the “order in chaos” that Bruegel is so good at depicting; like, it’s totally out of control, but it’s nevertheless somehow contained in a frame. So, those are things that I look at especially in times when it feels like things are out of control. And there are certain texts and poems and music that I go back to, too, but those Bruegel paintings, those stand out for me. They’re really emblematic.

Megan Craig and Rachel Bernsen, Colorada, 2015 (remainders from the performance work), Kunstverein Grafschaft Bentheim, Germany / Photo: Helmut Claus

The term “art therapy” was coined in 1942 by British artist Adrian Hill, who, while recovering from tuberculosis, learned how therapeutic painting and drawing can be. He noted that the practice was engrossing to both the mind and the body. According to some scientific studies, creating art has been linked to an increase in dopamine, a chemical related to feelings of love, pleasure and desire. Art can even help mimic the physical sensation of falling in love. Do you agree, and have you experienced art’s therapeutic potential yourself?

While thinking about your question, two very different kinds of artists immediately come to my mind. Frida Kahlo and the role of painting in her own process of healing. And Jean-Dominique Bauby, who was the author of the amazing book called The Diving Bell and the Butterfly and who was able to write through the experience of really intense illness.

Yes, I think art is healing. The making of art attests to a certain kind of plasticity. Whether it’s the plasticity of the brain or the plasticity of matter, it attests to there still being the possibility of making new connections, of remaking things, of experiencing failure that’s not final.

Yes, I think art is healing. The making of art attests to a certain kind of plasticity. Whether it’s the plasticity of the brain or the plasticity of matter, it attests to there still being the possibility of making new connections, of remaking things, of experiencing failure that’s not final.

Concretely, I’ve had two very different experiences of art in that mode and art-making as a form of survival. The first one relates to a painting residency I had in the World Trade Center in 2001. I had all of my supplies and paintings and my whole studio in the World Trade Center, and on September 11, I lost all of that work and subsequently spent many, many years processing a lot about that experience. I found that I really needed to keep painting that view, even though I no longer had access to it. At that point, for me, painting really became a kind of exercise in activating a motor memory. So, not like trying to actually see that view again, but to start to engage with the motor memory of having painted that view so many times before. It was a kind of memory of handling the paint, of moving relative to the canvas, and it was really a lot more like dance or choreography than it was like any kind of painting I had previously done. But I think doing that was crucial to my putting back in place the footsteps between work I was in the middle of (which just disappeared in a single moment) and whatever the next steps were going to be. Because it was like there was a literal hole in the trajectory of my creative life. And I had to find some way to fill it or to build a bridge over it. So that was the first experience.

The second experience is more recent. In 2018, I had a brain injury, a pretty serious concussion. And because of this injury I couldn’t read, I couldn’t write, I couldn’t focus my eyes, I couldn’t remember very basic things, and it took a whole year for these things to come back very, very slowly. At the time I got this injury, I had an exhibition coming up; it was meant to be a solo painting exhibition. But I just didn’t have the stamina or the focus to paint, and I didn’t have the physical mobility to paint, either. So, as a result of that, I started stitching. The things that I thought I might paint, I stitched them instead. You don’t need much movement to stitch, I didn’t have to look in the same way at the work, I could kind of rest my eyes rather than have that intense “painter’s vision” all the time.

I didn’t think about it like stitching as healing, but it was in fact a very critical part of my recovery. My brain rested over this time period. I really thought about sewing and stitching and mending in this therapeutic kind of way. And later I orchestrated some different public projects that involved collective stitching and questions about memory. Because I really found that the stitching played a role in my recovery. I had lost so much memory because of this brain injury, and as the fabrics got bigger and longer and more elaborate, my memory came back in different ways, and it really felt like the two things were connected.

I had lost so much memory because of this brain injury, and as the fabrics got bigger and longer and more elaborate, my memory came back in different ways, and it really felt like the two things were connected.

What are your feelings now when you look at the works you made then?

It still feels very new to me. I feel like I don’t really know about those works. I’m still interested in stitching, but I don’t need to do it now in the way that I did then. So, I think it’s a kind of crossroads for me in which I don’t quite know how to bring painting and sewing together, how to think about what those works actually mean, because it was so much out of necessity and in the moment that I didn’t think about it strategically.

You know, I didn’t think it would be interesting to use fabric; that’s just what I had available to me as a way forward. With those kinds of moments, I think it just takes so long to see your own work, so much longer than it does to see somebody else’s trajectory. To see your own work is such a mystery.

I think it’s also difficult to find out if, at the moment when you created those works, it was a conscious action or whether it just happened, subconsciously.

It has made me appreciate just taking advantage of the opportunities that arise. I was already experimenting with more collaborative work and doing other things leading up to the moment that I had the injury, but I think in my head I really still thought of myself as a painter. Like, I had to pick; I had to choose an identity and then kind of dig into it. I think the experience of having the brain injury disrupted my whole sense of identity. Because my identity is tied up with my memory, and I didn’t have my memory, so that triggered a whole bunch of things. But I think in a helpful way it just made me less concerned about having to say “here’s what I am” or “here’s what I do” and just be more open to, well, what are the materials available here, what does this space call for, what does this situation call for, and being kind of more flexible and ready to try things.

Maybe that’s also why art therapy is suggested for people who struggle with depression, because they sometimes may have a difficult time putting their feelings into words. Do you agree that art therapy can be helpful in such situations and may provide a way for people to express themselves? Also by helping to bring up the dark sides in order to get rid of them?

Well, there are experts and specialists in this field, but I’m not one of them. But this question makes me think of Julia Kristeva’s book Black Sun, which focuses on female depression (Kristeva is a professor of linguistics at the Université de Paris VII and a practising psychoanalyst. In Black Sun, she addresses the subject of melancholia, examining this phenomenon in the context of art, literature, philosophy, the history of religion, culture and psychoanalysis. – Ed.). One of the things I love about Kristeva’s work is the way she talks about women’s depressed speech and the way in which, to hear that speech, you have to be listening for something else than the words and the supposed meaning of women’s speech. So, listening to the rhythm and the breaks, the silences and the intonation – all of the stuff in between the words, which is really where all of the expression is happening.

I think that the therapeutic potential of art is in part related to that opening up of the gaps in language and finding new modes of possibility that are not anchored to words, that are not anchored to having to say directly “what’s wrong? why are you sad? why are you here?” All these questions that are deeply impossible to answer. But I guess it also has to depend a lot on individual cases, having a real sensitivity to what it is that might bring a person alive or might give them some additional means of expression.

I think that the therapeutic potential of art is in part related to that opening up of the gaps in language and finding new modes of possibility that are not anchored to words, that are not anchored to having to say directly “what’s wrong? why are you sad? why are you here?” All these questions that are deeply impossible to answer.

And while thinking about that, I’ve done some work with autism and in the autistic community, and I think it’s so important to have caregivers, educators, therapists and other people who are willing to meet the person where they are, who are willing to be taken up in whatever idiosyncratic thing is the practice or focus or organisation for that person. So, it could be arranging sticks in a line, or it could have to do with trains, or maybe it has to do with paper straws, you never know. But finding what that one thing is, instead of arriving with some set of materials and just expecting the person to pick them up and, for example, paint an expressive picture. That may not be possible. But I think for everybody there’s some inroad to that wider sense of expression – you just have to find the right material, the right context, the right delicate openness to what that is.

And also the right, delicate tools…

Yes. The work I’ve been most interested in tends to focus on situations where, rather than slot a person into a type – like, you know, here’s what’s wrong with them and here’s the therapy we should apply to them – there’s more invested in trying to know the person. Trying to know more about what it’s like for them to live, what it’s like for them to feel comfortable or uncomfortable in an environment or in the world, and then try to elaborate and bolster and sustain the things and the practices that make them feel most alive. And that can be anything.

I think historically one of the problems, especially in autism, has been that so many of the therapies for autistic individuals are about making the non-autistic individuals feel comfortable. Like, you’re making me uncomfortable, so how do I change you so that you don’t make me so uncomfortable? I mean, switch that paradigm and start thinking about how to join somebody in the world that they occupy, how to let them be who they are, and find additional range for that world. I think that really changes what therapy looks like.

I think historically one of the problems, especially in autism, has been that so many of the therapies for autistic individuals are about making the non-autistic individuals feel comfortable.

What happens with the concept of time when we look at art and are absorbed in it?

My husband is a musician, and he says that one of the things about playing music together with others is that it completely changes your sense of time. I think there’s something right about that, and that’s what art does for us. I mean, it happens very profoundly and bodily in music, because you find yourself moving to a rhythm that you didn’t choose yourself. But I think it also happens in the visual arts, and definitely in dance and other art forms in which you can be taken up by a tempo and by a sense of time that didn’t originate with you. That can mean that you’re suddenly slowed down, or you’re sped up, or maybe it’s a kind of rhythm you’ve just never experienced before.

But I do think that’s a critically important thing that can happen with art, because without your assenting to it, it’s a reminder that the tempo at which you live, or the tempo of your day, is just one among an infinite number of tempos. And, you know, sometimes that’s jarring. Like, you want to be the centre of your universe and you’re trying to move quickly from point A to point B. But I think mostly it’s a really good thing to be pulled out of your individualistic sense of time and reminded that time has all of these different shapes and forms.

I think mostly it’s a really good thing to be pulled out of your individualistic sense of time and reminded that time has all of these different shapes and forms.

In The Art of Seeing: An Interpretation of the Aesthetic Encounter, psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi writes: “The aesthetic experience occurs when information coming from the artwork interacts with information already stored in the viewer’s mind. The result of this conjunction might be a sudden expansion, recombination, or ordering of previously accumulated information, which in turn produces a variety of emotions such as delight, joy or awe. The information in the work of art fuses with information in the viewer’s memory – followed by the expansion of the viewer’s [awareness], and the attendant emotional consequences.” Do people “see themselves” in works of art – the ones they have in their private space and the ones they encounter in museums?

That’s true in the sense that we’re shaped by our experiences, and our vision is narrow to the degree that our experiences are narrow or biased in ways that are not even visible to us. But I’m a little resistant to Csikszentmihalyi’s computational model of aesthetic experience. Like, what gets programmed in then gets spit out in basically the same but slightly altered form. And I’m also a little resistant to thinking about aesthetic experience as exclusively an experience of recognition. I just don’t think that’s right.

I mean, yes, I think we tend to see according to patterns that are habituated, and habituated in ways that go beyond our control and beyond what we’re conscious of at any given moment. But I also think that aesthetic experience can be an experience of real uncertainty and unfamiliarity and not actually encountering the thing that we set out to look for. Not like the mirror effect, in which I’m attracted to it because it’s showing me myself.

For me, the most interesting kinds of aesthetic experiences are those that call you up short, that provoke you to not know what you’re looking at. And beyond that, to not know who’s doing the looking. I mean, art provokes the question of “who am I”, such that I’m now experiencing this thing.

For me, the most interesting kinds of aesthetic experiences are those that kind of call you up short, that provoke you to not know what you’re looking at. And beyond that, to not know who’s doing the looking.

I had a conversation some years ago with British sculptor Tony Cragg, and he said that, for him, each of his sculptures is like a part of a new reality. And you have to make a new relationship with it – as an artist and as a viewer as well.

It’s funny. I mean, I often have this moment in painting where the painting is almost done and I’m looking at it, and I wonder, “Where did that come from? What is that thing? I have no idea. Who made it? What is it?” It’s a little bit like, you might think about your own children as extensions of yourself, but at least for me, and having children now myself, they’re not like that at all; they’re totally their own things. I feel the same way about the work that I make in this studio. It’s not like a production of my little offspring, all in a row, who are going to line up neatly and march behind me like little ducks. No, they’re totally wild, like unpredictable foreigners. It’s actually pretty uncomfortable when you make a painting, and then it’s there in the studio with you. It’s like this moment of wondering, how will we live together? And how long will we have to live together?

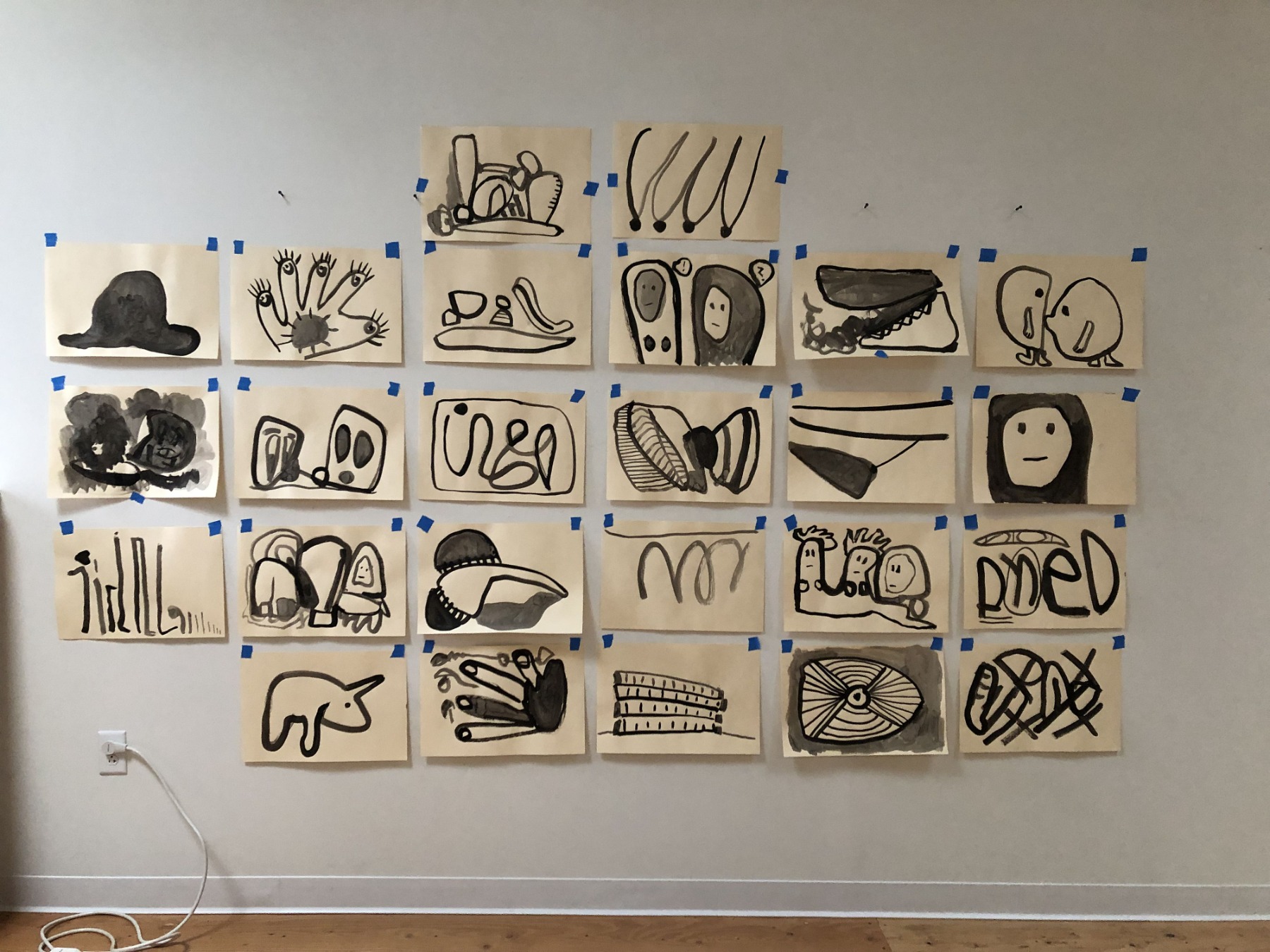

Megan Craig, Studio shot, works in progress, india ink on paper, 2020 / Photo: Megan Craig

Like having a stranger in your studio…

Yes, and it’s very disconcerting. And that’s, in part, what makes the studio such an exciting place to be. Because you never know who’s gonna be there.

What’s the role of art in the public space in terms of providing an understanding of art for the general public who’s maybe not so familiar with art in their daily lives? Does art have a subconscious therapeutic effect on people who are maybe not aware of it?

I can only speak from my own experience on this topic. In situations where I’ve worked on public works, the range of concerns and logistics is so different from when I’m working on something that’s destined for performance or exhibition in an institutionalised gallery or museum space. At least for me, the thing that has been so important in public work is the conversation that precedes the work. So, conversations with as many people as possible who will ultimately be interacting with and living with the work. A lot of community outreach, because if that’s not in place, then I think you wind up with a public work that can only make a statement, provoke, or have a so-called splash effect. But I think the most successful public works are long-lasting in the sense that the work itself becomes integrated into the life of the community in which it exists in such a way that it has different moments of appearance and disappearance. It’s not foregrounded all the time. It’s certainly not an egoist articulation of the artist. So, that’s a very difficult balance to achieve in public works, and I think there’s a whole range of successes and failures that we could investigate.

I think the most successful public works are long-lasting in the sense that the work itself becomes integrated into the life of the community in which it exists in such a way that it has different moments of appearance and disappearance.

But I think works in public spaces are so amazing when they work, because they do achieve that kind of blurring of the supposed line between art and life. And that’s a real gift to a community able to find a way of cohabitation with a work. That’s something we’re not allowed to do in museums and galleries, where there are all sorts of rules about how you move and where you go, what you can touch and bring and wear and eat or not eat. So, I think it’s crucially important to have lots and lots of public works that challenge all of those boundaries and also give communities a sense of ownership and participation and artistic practices as co-collaborators and part of the life of the work.

Megan Craig and Rachel Bernsen, Traveling in Place, 2017, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT / Photo: Stephanie Anestis

How important is it to include art education in school programmes? Quoting Susanne Katherina Langer again: “The arts objectify subjective reality, and subjectify outward experience of nature. Art education is the education of feeling, and a society that neglects it gives itself up to formless emotion. Bad art is corruption of feeling.”

I think it’s critical, in part because I believe that kids are naively artistic. You want to keep that alive in children; you want to provide as many possible avenues for keeping alive their curiosity, their willingness to experiment, their love of colour and a whole range of things that get steadily beaten out of them over the course of their education. I don’t think arts education should be formulated on an idea of how to make little artists; instead, it should strive to sustain the artistic spirit of a child, which is there naturally. All you have to do is not damage it, not kill it.

I love John Dewey’s work on this topic. I also think it doesn’t have to mean that a curriculum or a school that prioritises arts education doesn’t prioritise reading and math and writing and all those other things. There’s plenty of good evidence that when kids have access to enriching arts curriculum, they’re enriched across the board.

I don’t think arts education should be formulated on an idea of how to make little artists; instead, it should strive to sustain the artistic spirit of a child, which is there naturally. All you have to do is not damage it, not kill it.

Yes, we need more and better education from the very earliest stages of life, including a focus on being creative together, collaborating and finding the artistic value in a whole range of work. But we also need more disarticulated spaces for art that are not tied into this very stark hierarchy of success and everything else. I think artists are working on that, and there are artists who are always trying to transcend those boundaries. But I think it has become increasingly difficult. It’s not surprising that a lot of the public just feels exasperated with modern art and the idea of the artist. Also in regard to public works, which often feel like artists and officials swooping into communities and erecting monumental things without any sensibility for interaction with the people whose lives they impact.

How do you see the role of museums in this situation?

I think museums could and should be more disruptive of these divisions. But that requires really active disruption and outreach. Like, you can’t just sit back into the model of the traditional museum and just hope all goes well, because so often the museum is already located in a part of the city that’s primarily accessible to certain populations, there may be a very steep admission price, there may be an explicit or implicit dress code, etc. There are all sorts of things about museums that make them uncomfortable places for people to be in. And that’s not just for people who aren’t used to going to museums; it can be uncomfortable for anybody to be in a museum.

It might be too cold in a museum without wearing an extra layer, or maybe there’s no place to sit that makes any sense, or whatever. I think there’s just so much potential and opportunity for museums to think more creatively about this. And also to keep chipping away at the line between art and life and try to make art more open, accessible and a part of ordinary experience.

It’s very difficult to teach another person to look. What’s your advice as an artist and as a philosopher?

I think about learning to look and learning to listen as counterparts to each other. They’re the same difficulty. I think that the things you can try to teach have to do with a kind of willingness to experience silence, a kind of patience or hesitation, humility, openness to revision. You might, for example, set up certain kinds of exercises with students that let them practise being quiet, that let them practise trying to hear what one of their peers is saying, trying to demonstrate that they’ve in fact heard what their peers are saying and not just what they wanted to hear them say. These could be very low-level educational exercises, but I think those sorts of things are so important, because we’re living in an environment that’s so fast right now. It’s so digital, with social media and the 24-hour news cycle – everything’s so fast, and it’s working against the option of taking time to respond, or even to not respond, to hold your response. Those are the sorts of things that I think are really important. I think learning to look at something is so connected to being able to withstand the discomfort of waiting and not speaking, not rushing, just that kind of withholding. Which is hard.

Maybe that’s why many people are turning to meditation right now. Because they feel this necessity and urge for silence, to just be with themselves.

I think that we – well, especially in America, but to some degree globally – we’re accosted by information right now. And the pandemic has exacerbated this in the sense that we’ve been shuttled on to our devices even more. Our devices are engineered to make us reactive, to make us click, to make us scroll, to make us just machines of reaction. So I do think that it’s a real issue, and it’s a project to figure out how to resist the social engineering that’s going on and create enough space for things like silence and hesitation. I mean, it’s all tied to the ability to pay attention and to listen.

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about English psychoanalyst Donald Woods Winnicott’s idea of “holding environments” and how, especially in cities, we need more holding environments, which is the idea of a space where people can be quiet together. It’s a sort of unspecified way of being together in which you don’t have a role or a script or a set of expectations. You don’t have to react; you’re allowed to just be silently together.

Thank you very much!

Title image: Megan Craig, Studio Portrait, 2019. Photo: Nick Lloyd