We have a hospital where we can really innovate

An interview with Trystan Hawkins, Arts and Patient Environment Director at CW+, the charity of Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

London’s Saatchi Gallery is showing the exhibition “Journeys: The Healing Arts” – in cooperation with CW+, the charity of Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust – through January 13, 2022. The show focuses on the healing power of art and its role in promoting the physical and mental well-being of patients and hospital staff alike, as well as speeding up the healing and rehabilitation process. This is the first exhibition of its kind, and although it’s undeniably been stimulated by the pandemic, it is striking testimony to a holistic approach to patient treatment – one in which the process is seen as a whole, and where the best and fastest results can be achieved by combining the latest medical skills and discoveries with an environment conducive to a successful healing process, filled with a positive mood and spirit. In other words, physical health with mental comfort for all – patients as well as doctors, nurses and hospital staff.

The CW+ visual and digital arts collection displayed in Chelsea and Westminster Hospital is made up of over 2,000 artworks, many of which are bespoke commissions. The arts have been integrated into the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital’s environment since its inception in 1993, which is when the now widely acclaimed and award-winning CW+ Arts in Health programme was also established. The programme encompasses a unique blend of a broad variety of arts media and forms of expression – visual art, performing arts, live music, dance, art and craft workshops, film screenings, innovative design, and even specially created green spaces.

In response to the pandemic and the major impact it is having on mental health, at the beginning of this year the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital collection was supplemented with the innovative digital art installation “Immersive Healing Art System” (IHAS). Devised by the London-based studio Genesis, IHAS has been tailor-built with an AI-algorithm-fitted system that detects a subject’s mood and emotions through facial scanning and sensors, and then attempts to influence a positive reaction by creating a unique audio-visual art piece that calms, relaxes and improves the subject’s mood.

Works by more than 20 artists are on view at the Saatchi Gallery exhibit. Featured artists include Anouk Mercier, Gary Embury, Lucy Ward, Emily Thomas, Olivier Kugler, Tim King, Carlos Penalver, Accademia, Paolo Estrella, Min Young Kim, James Hope-Falkner, Owen Diplock, Dan Stockmann, Morgan Beringer, Kit Mead, Eda Sarman, Sara Choudhrey, Stateless Studios, and Genesis Arts, as well as Brian Eno,whose digital artwork is premiering at Saatchi Gallery and will move on to the hospital when the exhibition closes in January.

Project Willow, 2019-2021 by James Hope Faulkner. Digital Film porojection at the Saatchi Gallery / exhibition “Journeys: The Healing Arts”

The CW+ Art and Design programme is led by Trystan Hawkins, who has previously led a number of other visual arts institutions, including Wysing Arts Centre and the Royal Academy of Art in Bristol.

How has the pandemic shaped the role of the arts in healthcare – and the notion of health and healthcare in general?

You know, the way we define art is very broad. I suppose at the heart of it, it’s about human interaction. It’s about talking. It’s about sharing with people. It’s about making time and looking out for each other.

In terms of your question, and how the pandemic has changed our approach to arts and healthcare – if I think back, in the beginning of 2019 I’d spent some time in Japan. The Japanese work ethic is pretty extreme, but one of the things I noticed in the hospital there was that doctors or nurses would just go and lie down or sit and appear to be asleep. And that was allowed, that was accepted as part of the way people work. And I thought, God, you know, that wouldn’t happen in my hospital...

But one of the things we did early on in the first pandemic was install sleep pods for staff, and now it’s just accepted that not everyone works in the same way. You know, people’s body clocks may be different. For instance, I get up at five o’clock in the morning, and by 11 o’clock I’m really starting to crash. I don’t smoke, so I can’t go for a cigarette, but I need to just recharge my batteries. So we’ve created physical spaces where that can happen in the hospital, and I think that’s recognised now as being really important. We are also offering yoga and exercise areas as well as mindfulness activities to help relax staff after long shifts in the clinical environment.

I think mental health has really changed in terms of people understanding and acknowledging that. If you look back in terms of medicine, we’ve been really good at looking after all of the major organs, but the brain, I think, has been forgotten to a greater extent. So if you think about something like delirium, probably everybody knows what delirium is, but two or three years ago we weren’t even screening patients for it. We didn’t know if patients had it. Whereas now we’re screening all patients, and guess what – a lot of patients have this condition. And that can be pretty serious in terms of what happens to those patients. I think if you have delirium, you can be up to four times more likely to die within the next 12 months. So this is really important.

I think recognising the importance of mental health in patients, and also in staff, has changed radically. In my case, if I think about what I’m offered now in terms of mental health support, that didn’t in the same way before Covid.

In terms of the arts, the boundaries are so blurred, but the arts have been a brilliant vehicle for managing a lot of what we’ve all been through, which has been incredibly challenging. Admittedly, access to art has sometimes been difficult; we’ve had a whole virtual strand to our programme that’s worked for a lot of patients, but for some patients who don’t have that kind of digital literacy, it’s perhaps been harder. During COVID, I was actually working in COVID wards helping out with very ill patients. And when you’re that ill, engaging with some kind of screen is probably the last thing you want to do. I know if I’m really ill, I can’t watch a film or read a book. I may want to talk to somebody or listen to music, perhaps.

Speaking about the patients who need critical care, your hospital recently underwent expansion and redevelopment of the Adult Intensive Care Unit (ICU), creating a first-of-its-kind patient-led approach to care by improving the recovery and wellbeing of patients through incorporating the latest innovations and digital solutions (which can be personalised) to reduce anxiety, pain and stress. The acoustics, lighting and furnishing have all been selected for the patient’s brain, body and senses to rest and heal more effectively. What is the importance of the environment of the ICU for the patients who find themselves there?

It’s something we’ve been working on for probably about four or five years. It’s taken a long time – the old ICU was designed in the 80s, opened in the early 90s, and quite quickly became out of date. In terms of the space around the beds, there were roughly about 13 square metres, so not very big. The light quality was pretty awful; also the noise levels were very high. Very high means in the region of about 90 to 100 decibels. And if you need to sleep, you ideally need an environment around 50 decibels.

So you could say that the patients in that environment couldn’t sleep. And they’re your most ill patients, so straightaway that’s putting them at a disadvantage. We worked for a number of years designing what would be the best kind of environment, and now that it’s open, we’re measuring the changes that have taken place. I’m really hoping we’re going to see a dramatic reduction in the number of patients developing delirium, that their quality of sleep will be better, recovery rates will be better, and that mortality rates will go down.

There’s also the staff aspect – if the staff is working in a noisy environment, that is not good. Studies have been done that show the effect that has in terms of staff burnout, staff mental health, making mistakes, etc. So we did things like improve the acoustics of the rooms; we are measuring the air quality, and that is also better. We’re also giving people choice over their individual space. For instance, I might like the lights really bright, while someone else might want them dimmed. The same goes for temperature control – this happens in a lot of public buildings where there is one temperature, but we can actually control that on a local level.

And then things like the quality of daylight – making sure you’ve got good daylight coming into that space. Each room has really good views across London, and the quality of light is really good. And then we have artificial lighting that follows people’s circadian rhythms – the body’s natural clock in terms of knowing when it is night, which promotes sleep, and when it is day and time to be more active.

We are currently working with the ICU team at Chelsea and Westminster hospital on a sleep study to review using virtual reality in an ICU environment and how this can impact sleep quality, and, in-turn, psychological and physical symptoms.

One of the tendencies we saw during the early days of the pandemic (and which seems to still be ongoing) is our need to reconnect with nature – having lost this connection in the urban environment, many people moved out of the cities and into the countryside, or at least took up gardening. This autumn the new indoor botanical Sky Garden at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital opened, yet another part of the redevelopment of the hospital’s Adult ICU. What is nature’s role in the healing process, and is there room for that in a clinical environment? Has there been measurable impact on patient experience and recovery from these kinds of nature-based initiatives?

There’s been a lot of research that has shown that connection with nature has many benefits in terms of wellbeing. So to that end, a lot of the artwork we’re working with draws inspiration from nature. We have a whole programme called RELAX digital – it’s basically about 60 hours of film content that runs on screens in patient bed areas and shows beautiful scenery. It’s a bit like a screensaver, but we’ve worked with artists to create it. Sounds can be heard moving around the room as they travel from one speaker to another, creating a three-dimensional audio space of flying birds and distant rolling waves. Early feedback from patients indicates that this kind of natural soundscape offers a pleasant sound mask that effectively covers up disturbing noises.

We’ve also looked at how we can create physical gardens, the green spaces within buildings; we’re trying to create as many pocket gardens as we can. The other thing about our work is that we look after all of the things that we create – we don’t expect the hospitals to do that because they’re extremely busy, and the money available for healthcare is always shrinking. The charity I work for takes on that responsibility.

These are spaces where patients can go. It’s where family can go. For instance, when a patient who’s been in the ward for a long time starts to mobilise, they might go and do some of that therapy work within that space. It could be that they’ve got a pet, maybe they have a cat. We can’t take the cat on to the clinical ward area, but we can bring it into the garden.

And the effect that has is just immeasurable; you can just see with your eyes how beneficial it is. Another benefit is a very practical one in that the gardens can actually clean the air, and we keep this aspect very much in mind when selecting the plants. Moreover, the plants are cared for organically, without chemicals and pesticides.

At the same time, they’re just nice spaces to be in. For example, we may have a patient who’s going to be passing away, and they can choose to be with their family and die within a less clinical space. From time to time that does happen.

I already mentioned the sleep pods. So again, within our green areas we have areas where the staff can go and relax in the sleep pods. You can lay down and take a nap for 20 minutes or longer, falling asleep to specially composed music, ensuring that you are well rested before or after a shift.

As you know, the weather in England is not so great. So where we can, we’re trying to create indoor garden spaces as well as outdoor spaces. The other thing we’ve tried is giving wards an area of a garden which they look after. They might want to plant some herbs or tomatoes there – we’ve got some things they can grow, and they can eat them as well.

Food is generally not that great in hospitals, and we haven’t really started to look at it in-depth, but it’s something we would love to do. Because I’m a big believer in that if you’re feeling ill, but you have a good meal and sleep well, quite likely the next day you’ll feel better. And that’s without any medicine. So the body has the ability to heal itself if you give it the right kind of ingredients.

The other thing we’re doing around plants and the natural world is – I don’t know what it’s like in Latvia, but here in the UK, when my father was in hospital, I couldn’t bring him flowers. Whereas if I was in France or Japan, I could. This is to do with infection control – hospitals are worried about bacteria or germs coming in, and that’s why we’re not allowed to give our loved ones plants.

So we’ve been looking at how we might create digital plants. There is a brilliant group of artists called teamLab based in Tokyo, and they create these incredible, immersive environments and do beautiful work with the natural world and plants, birds and butterflies. We’re trying to create a version in which, for instance, if I was in hospital, I might choose a sunflower. And I can have that “sunflower” at my bedside – it might close up at night, it might move with the wind, it might be affected by the weather, but it’s something I can have by my bed. Ideally, it would be a hologram.

It’s also one of the things we’re exploring now with Min Young Kim, an artist/designer based in South Korea – how can we create digital things that represent the outside world. Moreover, things that we can nurture, things we can look after, and perhaps, also things that are neutral, because within a hospital, patients are very disempowered. And as you know, the staff is usually very busy. Often the only contact patients have with another person is when they need to take their next tests, their blood pressure, etc. And if we can create neutral things within that environment that can become a talking point, that can be really beneficial as well. I’ve seen many examples of where that’s had really positive outcomes.

CW+ owns and curates the most comprehensive collection of contemporary British art on display in a hospital. The “Arts in Health” programme was established along with the opening of Chelsea and Westminster Hospital in 1993. You’ve mentioned that the collection has been really diversified in the last few years. How are works selected for the collection, and how much has it changed?

The CW+ collection has changed very much over the years. The hospital opened in 1993, and there were some old artworks that came over from a hospital that existed before then. So really, in the early 1990s the main focus of the arts programme was around music – putting on musical performances – and the collection was ancillary. I joined around eight years ago, and at that time we were actually registered as a museum and the primary focus of our work was already around the collection.

I come from a museum background, and I kind of struggled with the notion of – well, we’re not really a museum, we’re a hospital. And hospitals change; they change all the time. So we had a lot of artwork that we weren’t showing – we had probably about 600 works in storage. And to get rid of them was really complicated because we were a “museum”. So the first thing we did is drop the “museum” status.

A lot of the artwork we had wasn’t that great, either. We’ve been able to kind of refresh the collection – we’re able to sell things. Some of the work was actually worth quite a lot of money, but it wasn’t the right kind to display in a hospital. Moreover, we’re now able to respond to changes, such as when the hospital renovates or builds new additions. For example, there was a case where a space that contained a specially commissioned artwork completely changed its function, and we had to remove the said artwork.

As a curator, I used to get really worried about such things, but I’ve stopped now. Because this is a hospital – it’s a living building; we’re here to have an impact on people’s lives, not be an art gallery. Art has a really important role within the hospital, but it’s not essential. I think we’re much more flexible. Now most of the projects we’re doing are more temporary.

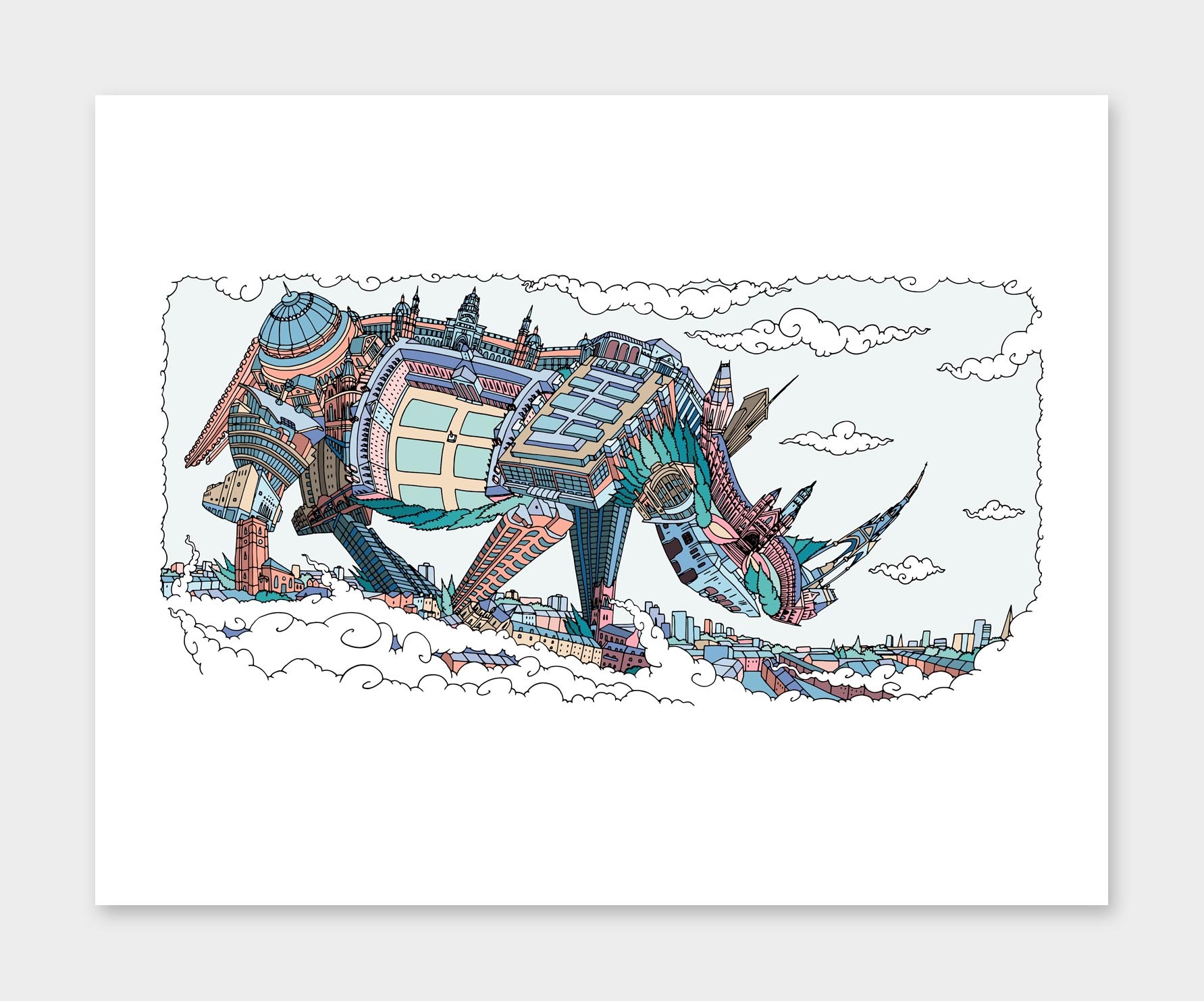

Andy Council. Mother Rhino.

Personally, I think there’s nothing worse than a piece of public art that was created 25 years ago, and which now looks just awful. It’s just not relevant. The other thing about the collection was that it was very much from the 1980s and 90s, and not representative of the communities that we’re now working with. For example, there weren’t practically any works by black artists. So we’ve been quite proactive in terms of commissioning artists that represent the broader communities that we’re now serving; the collection has also become more diverse in terms of the kinds of art forms it contains.

We now do commissions that have a sell-by date, so maybe after three years we’ll take a certain work down. In some cases we might sell it, or we just might scrap it. We’re much more flexible now. We’re doing a lot more work that is digital as well, because that’s very easy to change.

We’re trying to commission a range of different artists, from artists that might just be starting out to really successful artists. We’re also looking at the process, at how artists work. A lot of the work we do is about relationships. Occasionally, it just may be an artist coming in and spending time with patients on the ward. And maybe there isn’t even a product at the end of it – it’s about the process of working together. It’s about the conversations. During COVID, we’ve had a team of artists coming in and doing drawings – just drawing and documenting stories. I was aware of this being a really challenging time, and it was a moment in history that we needed to capture. We’re kind of still in it, and we don’t really know what we’re going to do with that work. But I anticipate that we may do a book or something like that around it.

I guess my work is really about experience and environment; and sometimes that doesn’t involve art at all. It’s around design, or it could be about the interpersonal relationships between teams, the way that they talk to each other, the way that people physically move through spaces. I think we kind of blur or muddle the edges between what is art and what are the things that make the hospital work.

We’re really lucky that we have a hospital where we can really innovate – we can experiment, we can take risks. So for me, what is really important is that we can share with others the things that work for us. A lot of the digital things that we produce we offer free of charge to any other hospital in the UK. For example, we’ve got a big new strand of work about adolescent mental health. A growing number of young people in the UK are developing mental health issues, and that’s really sad. And we don’t necessarily have the best way of treating those patients. So we’re going to be experimenting with some new models of care, and if they work, we’ll obviously share that experience with others in the UK as well as with the rest of the world.

Midlands, 2021 by Brian Eno. Digital film at the Saatchi Gallery / exhibition “Journeys: The Healing Arts”

The exhibition “Journeys: The Healing Arts”, currently on view at Saatchi Gallery, also includes a new commission created by the musician and artist Brian Eno. This is not your first collaboration with Eno, who is well known for his healing art installations. Could you go into a bit more detail about this collaboration and the role of music in a hospital setting?

When I joined, which was in 2013, I wrote down a list of people we’d like to work with. We had quite a number of artists, and Brian’s name was on there. I went to see the work that he’d done in a cancer centre down in Hove, near Brighton. We just started a dialogue, and he came in. The usual way a project starts is with the artist putting on scrubs (the blue nurse’s uniform) and just spending time in the environment. Brian came in and spent time in our emergency department – talking with staff, talking with patients, getting to understand the environment. And that was with the aim of producing an artwork for emergency department.

These projects are very collaborative. We work very closely with the staff, and we also try to involve patients in as many ways as we can.

I’m familiar with Brian’s music and I like it, but when working with an artist, you have to take into consideration that not all people will think the same way about their work. It’s possible that someone may say – well, that’s not music. That’s why this mutual cooperation – the time the artist spends together with the staff – is so important: the staff comes to understand how the artist works, and the artist is able to develop a work that is appropriate for the environment.

In Brian’s case, the work that he previously developed for us was a triptych. It was three screens depicting a garden that he created. It was a kind of moving image of a garden – very, very slow, over a period of, I think, about 20 to 25 minutes. It was in our emergency department for about three years. We’ve now decommissioned it – we’ve taken it down – and he’s created a new work called “Midlands”, which is at Saatchi Gallery at the moment. He finished that probably three weeks ago, and it will be going into the hospital in January. Works like that are not necessarily permanent – they are temporary. And because they have a musical component, it is very important what kind of environment they are placed in – it may work in some areas but not in others.

In terms of music, we generally use music for the hospital. Most days there are musicians performing somewhere in the hospital, and we digitally stream these concerts to ICU patients’ bedsides, thereby providing emotional comfort and an escape for the seriously ill.

Before COVID, we would do public performances in the building’s public areas. We have lots of sound systems that can play things like a Spotify playlist, etc. Actually, most areas of the hospital have the possibility to play music, if needed; and where possible, we give patients control over that. If you come into our emergency department, each of the treatment rooms has a little switch on the wall with nine settings – clicking through them, you can find different genres of music: jazz, ambient, classical, etc. In this way you can very quickly personalise that environment, which I feel is really important – giving people some control over things that are important to them in that moment. And those things don’t have to be complicated.

We use the speakers in the ceiling, and the little switch on the wall cost maybe 80 euros to put in. It’s really simple and low technology, but it works. So yes, music is incredibly important. It’s probably one of the top-tier things because it’s so simple as well.

There is also a lot of research going on. One of the first randomised control trials we did was look at how effective visual arts and music are within a healthcare setting, and what the clinical benefits are – of which there are many. We’ve got a study going on within the ICU that looks at the effect of music on patients within an intensive care environment. Evaluation and measuring impact are absolutely key.

There is another thing that is equally important – cost-benefit analysis. Within a lot of our research projects, we’re trying to find out if there’s a saving in terms of money. Yes, we know that these projects have emotional and psychological benefits, but are they actually saving money in terms of people getting better more quickly? Can a treatment be administered and finished more quickly? Because if money is being saved, that’s beneficial to the hospital as well – a hospital is a business. We’re looking at health economics – something that is often quite difficult to measure, but it’s kind of the “Holy Grail” of the field. There are many hospitals that won’t do this kind of work [art therapy] because they think it’s a waste of money – why would we spend money on art when we could be spending money on this or that? But we have evidence proving that there are financial benefits, which are just as important as the clinical benefits – people are getting better quicker. And that’s obviously much nicer as well.

Chiswick artist Marthe Armitage installing her intricate, signature wallpaper designs in the Cardiac Care Unit and older patient wards at West Middlesex University Hospital. Photo: Owen Richards

How open are patients to these kinds of art experiences in a hospital setting? Obviously, their conditions are very different in each particular case, not to mention their personal and cultural backgrounds. Do they welcome these sometimes completely new experiences?

It’s really important that we have very close relationships with the clinical teams working on the different units. We’ve got a cinema in the hospital as well – we have volunteers that go around and ask patients if they want to go see a film, what kind of films they like, etc. And just this afternoon we’ve got an artist coming in, and we ask patients if they would like the artist to come and spend time with them. These are regular activities every week.

For our first commission at West Middlesex University Hospital, we approached renowned British wallpaper designer Marthe Armitage to design installations for the Cardiac Care Unit and older people’s wards.

Chiswick artist Marthe Armitage installing her intricate, signature wallpaper designs in the Cardiac Care Unit and older patient wards at West Middlesex University Hospital. Photo: Owen Richards

She is 91 now and was, I think, around 86 when she came to the hospital. Armitage’s work is characterised by beautiful hand-drawn designs that are hand printed from lino blocks. Her coming on to a ward and working with older people who might have dementia (many of whom were much younger than her) was an incredibly empowering experience.

Getting the right kind of artists to work within a particular environment is really important. And that takes time, and it doesn’t always work. You don’t always get it right, but at least you’re building towards that potential.

Over time, with long-stay patients we were able to get to know who they are and what they like. It may be that we’re talking to the families. In the past we’ve had patients who may be unconscious, but we know that music is really important to them. We had a patient recently (this has been published in the press, so he won’t mind me mentioning it) who had worked with The Beatles, and music was incredibly important to him. So while he was unconscious, music was played and various images were put up around his bed area – he went on to make a great recovery, and we know that music had a beneficial effect on that.

Tigerplay Playroom

Last year, just before the second UK lockdown – together with photographer and author Maryam Eisler, arts patrons Maria Sukkar and Shirley Elghanian, and photographer David Taggart – you launched “Republic of YOUmanity”, a fundraising initiative with the aim of uniting the local community during a time of isolation and disconnection. As part of this project, shops around Kensington and Chelsea that had closed down because of the lockdown were transformed into collaborative pop-art galleries displaying giant prints of Taggart’s photographs.

CW+ has a big team of supporters that support the work we’re doing. The aim of this initiative was raising money for charity. It was during the pandemic, everything was closed, and we thought – how can we use shop windows? How can we celebrate humanity? Besides those kind of pop-up exhibitions, we did and online talk as well, which was incredibly successful. And on the back of that we’ve developed a whole series of talks.

The main thing is that we have people out in the community who have used the hospital, and they want to give something back. This is something which is, I think, quite new. I think in America it is probably pretty normal, but in the UK there’s the expectation that you pay your taxes, and those taxes pay for hospitals to operate. But that is really changing now.

Artworks created by the schoolchildren are integrated into wall design

In addition to that project, which was for a new ICU for adults, we did one for the redesign of the neonatal children’s intensive care unit. We went out and asked people to help, and raised 12.5 million pounds – an incredible amount of money; it was unthinkable. And it happened in quite a short space of time, and largely through donations from people who had used the hospital and wanted to give something back.

Something that is really changing is that people recognise that they need to give, and obviously, during COVID, people have been incredibly generous. In the early days of the pandemic, we had real problems with food – with buying food, shops were running out of food, etc. The staff working in the hospital would finish their shift, go to the shops, and there was no food – that became a huge issue. Very quickly we were able to mobilise the communities in terms of bringing in food and making sure that everyone was eating. That was just incredible in terms of building a sense of community, but it also built connections with new people who have carried on supporting our projects.

I think that sense of giving back is something new here, and the “YOUmanity” project was part of that. Personally, I feel one of the really positive things to come out of COVID has been building a sense of community and just looking out for each other. You know, if I think about where I live, I’ve gotten to know new people that live nearby. This includes older people who may need checking up on or help with shopping, as well as just people overall being more mindful of each other. That has been a positive thing, and hopefully it will stay.

Since COVID, do you think collectors have altered their approach to collecting? Have their interests or choices changed?

In terms of collecting, I don’t know – this seems to still be a very buoyant market. But I suspect that going forward, we’re going to have difficulty raising money for projects and commissioning projects. The projects that I think will be successful are the ones that have more of a community focus, that touch on more areas of well-being than perhaps just being an artwork in its own right. And perhaps that is the correct way to go – rather than obtaining a commission for an artwork with a certain life expectancy, use the funding for a whole programme of work that has more approaches and greater impact.

In terms of the ability to raise money in the way that we have traditionally gone about it, I think it is going to be challenging. There is less money around now, and it’s probably going to take decades to recover from what’s happened. In the UK we have Brexit, which has been catastrophic, and now we have COVID. The economy is in a really bad place and things are going to be harder financially, but what I would hope is that this sense of supporting important facilities is starting to take root. I think people now recognise that what they do has importance.

Seasonal (RELAX Digital) by Morgan Beringer. Digital film at the Saatchi Gallery / exhibition “Journeys: The Healing Arts”

How has your own personal relationship with art and what you look for in/through art changed since you’ve begun working at a hospital charity?

Very good question. Before I joined the charity, I was director of the Royal Academy of Art in Bristol. As you know, that is a museum with a big collection, and I was kind of the curator of it. Initially, when I came to the hospital, I really struggled with the curatorial integrity regarding some of the things we were doing. For example, we may be commissioning work for one space, but directly opposite, there’s a work that’s maybe 20 years old that just won’t work with the new artwork, or the quality of the two works will be so different. Ideally, you would strip out everything and re-curate, but the reality is that the cost of doing that would be totally out of this world. So you’re not going to do that.

I think I’m less precious about things now. I accept that the building changes and that things will happen, sometimes at really short notice. This is a hospital; it is a working building and you have to work with that. Ideally, you will try to be involved in that process, but you can’t always be. An example: you’ve spent three years really carefully designing a new ICU. It’s all beautifully designed, and then they’ve stuck another set of doors in because they need to stop people from going into one area from another. And it all happened unexpectedly and really quickly. So the doors weren’t the same as the doors that are already in there. But it is what it is, and we need to do things quickly. So, yeah, just being flexible is really important.