If this could be art?

Express interview with Liisa Kaljula, curator of the exhibition “Harku 1975: Objects, Concepts,” on view at Kumu Art Museum (Tallinn) until 17 May 2026

In December 1975, a small group of young artists and scientists organised the art event Harku 1975 at the Harku Institute of Experimental Biology near Tallinn. Among the participating artists were Leonhard Lapin, Sirje Runge and Raul Meel, while the scientists were represented by Tõnu Karu, then a junior researcher at the Institute of Cybernetics of the Academy of Sciences. The event caused a scandal among official circles because an unexpectedly large number of young artists attended, and its atmosphere resembled that of a rock concert.

Marking the 50th anniversary of this legendary event, the current exhibition in Kumu’s project space aims to reconstruct Harku 1975 piece by piece. It brings together works from the collections of the Art Museum of Estonia and the Tartu Art Museum, as well as from several Estonian private collections, including works long thought lost or destroyed.

Exhibition view of "Harku 1975. Objects, Concepts". Photography Stanislav Stepashko

Exhibition view of "Harku 1975. Objects, Concepts". Photography Stanislav Stepashko

The curator of the exhibition, Liisa Kaljula, writes in her preface: “The event had received official permission from the Artists’ Association as a meeting of young artists and scientists. However, in addition to the approved seminar day, an exhibition was also arranged in the main hall of the Harku Manor. The event has since entered the history of Estonian art as the last unofficial art exhibition of the Soviet period, and marked the transition from pop art to conceptual art. It also stands as the first multimedia event in Estonian art history: combining a concert by Sven Grünberg’s progressive rock ensemble Mess with Kaarel Kurismaa’s kinetic sculptures”.

We contacted Liisa Kaljula to learn more about “Harku 1975: Objects, Concepts,” its context, and the period 50 years ago, when art and science were mutually curious and inspiring – particularly in experimental circles, including within the “Soviet bloc”.

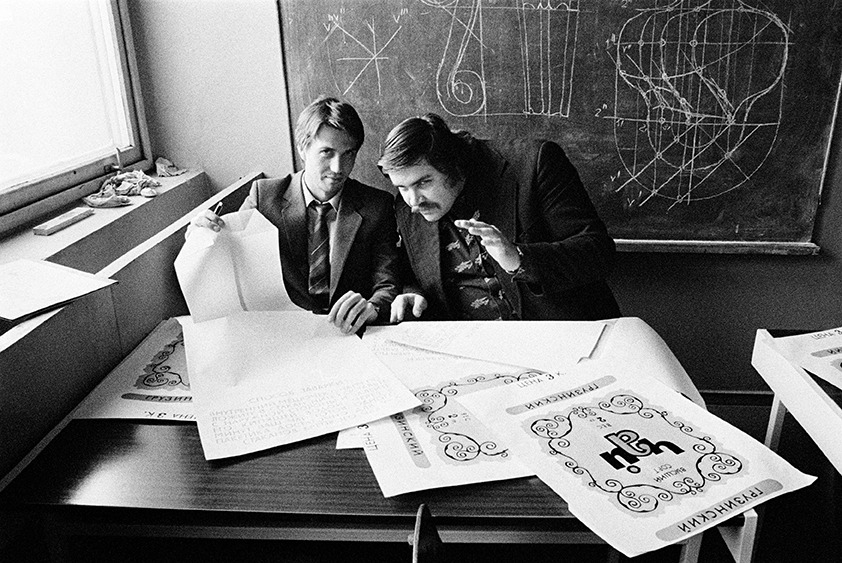

Jaan Ollik ja Villu Järmut with the work Tea Bags. 1981. Art Museum of Estonia. Photo: Tõnu Tormis

Why is the original Harku 1975 event important in the history of Estonian art, and why did you feel it was the right moment to revisit it now?

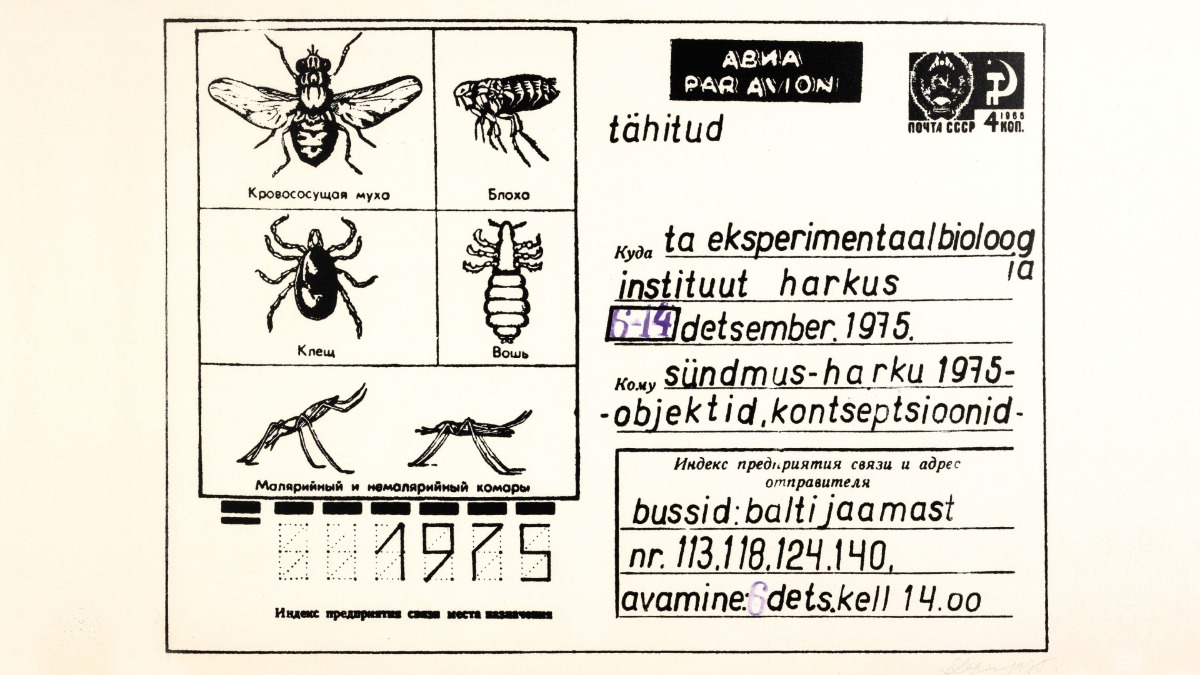

Harku 1975 is famous as an event that brought together young artists and scientists, but also as the last unofficial exhibition in Estonian art history of the Soviet period. Because in Tallinn and Tartu, unlike in Moscow, there was no need to organize apartment exhibitions after 1975. From 1966 on, abstract and surrealist works were allowed in official exhibitions and the art life in the Soviet Western periphery enjoyed several freedoms that were unthinkable in the center of the Soviet universe. But why I wanted to revisit Harku 1975 now, was not merely because of the 50th anniversary of the art event, even though it is important to celebrate these kind of landmark moments in art history, but because I wanted to question the meaning of the exhibition in Estonian art history besides being the last unofficial show organized by rebellious young artists and scientists. Namely, my hypothesis was that it was one of the first platforms of Conceptual art in Estonia and it all seems to make sense when we look at the location – Harku Institute of Experimental Biology – and the flyer of the event that was decorated with scientific drawings of insects. But the problem is – a bigger wave of Conceptual art never followed in Estonian art.

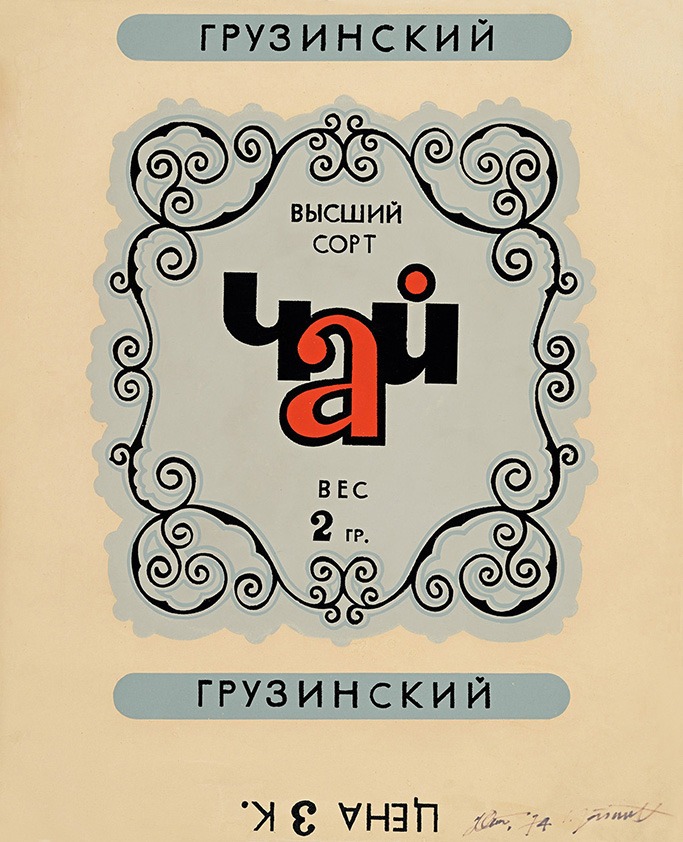

Villu Järmut and Jaan Ollik. Tea Bag. 1974. Graphic object, serigraphy, silk paper and plant-based filler. Art Museum of Estonia

The 1970s were a period when art and science increasingly intersected, particularly in experimental circles, including within the “Soviet bloc”. What prompted this interest, and how did it influence the subsequent development of both fields?

I very much agree and I think it´s better to admit that even experimental circles were nonetheless affected by the surrounding socialist society, which was obsessed with the so called scientific-technical revolution. In Estonia, young artists with architecture and design background Leonhard Lapin and Sirje Runge manifested and called their contemporaries to make so called Objective art in 1975. Because they really believed that art needs to resonate with its time and the surroundings, even if both were abhorrent to the artist who was, accidentally or by the will of God, born in the Soviet Union. Soviet Union was one of the most industrialized countries in the world, but the time of Lapin and Runge was already the time of the early postindustrial society, when computers and cybernetics started to play a growing role not only in the West, but also in the Soviet Union. In Estonia, the interaction between young artists and scientists indeed influenced art at the time, because in the ending seminar of the Harku event, researcher from the Institute of Cybenetics Tõnu Karu showed slides of breast cancer and astrophysics and asked if this could be art. And after a long silence in the audience, the artist Raul Meel replied that these scientific illustrations could be called art when they were placed in the context of the art exhibition. This might be the earliest definition of Conceptual art in Estonian art history.

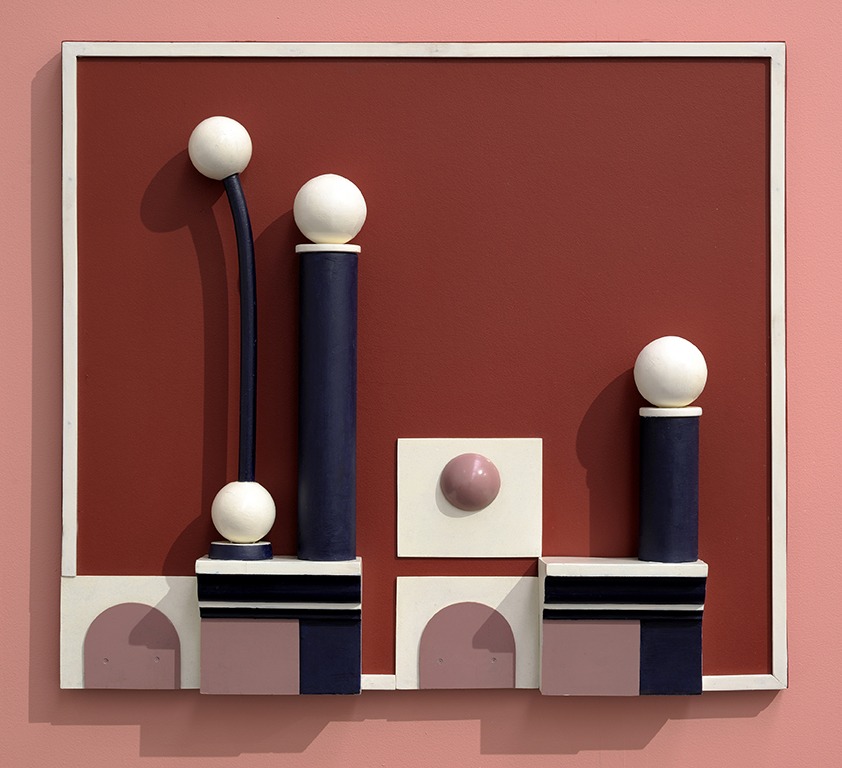

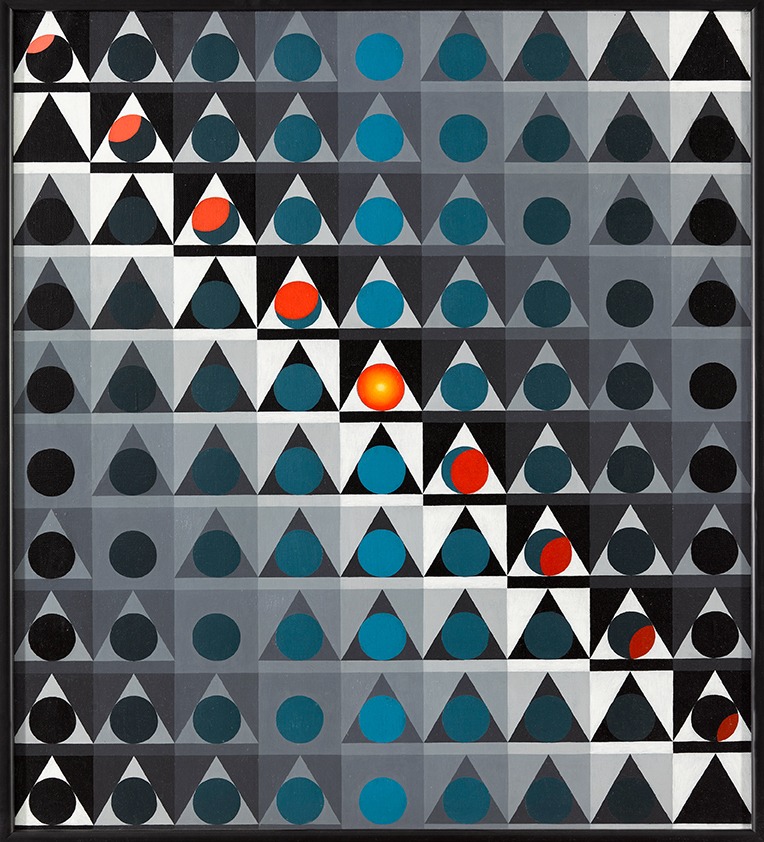

Kaarel Kurismaa. Object I. First half of the 1970s. Oil on wood. Art Museum of Estonia

Kaarel Kurismaa. Object II. First half of the 1970s. Oil on wood. Art Museum of Estonia

Which ideas or artistic approaches from Harku 1975 do you think feel most relevant to contemporary audiences today?

I think for the contemporary audiences, the reconstruction of Harku 1975 feels very natural, because in today´s art exhibitions, playing and challenging the old mediums such as painting, graphic art and sculpture is very common. But it´s important to remember that this exhibition was born in the Soviet Union where painting and graphic art meant framed rectangular objects attached to the wall and sculpture meant solid, static objects placed on a postament. In Harku exhibition, all the traditional art mediums were questioned and challenged: Sirje Runge´s painting was an immersive altar-like object that embraced the viewer and Jaan Ollik´s and Villu Järmut´s graphic art was an installation consisting of witty objects that enlarged the Soviet Georgian tea bags and hanged from the ceiling, and Kaarel Kurismaa´s sculptures were moving and making sound. So, the contemporary audience might be a bit surprised that contemporary art was not imported to Estonia after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, but its roots go back to the 1970s, which was in many ways a very modern decade also in the socialist block. But there might also be one thing that the contemporary audiences envy and it´s the way that young artists and scientists cooperated and held together in the Soviet era, whereas today art and science are one of the most competitive and lonely fields because they need to operate in the context of the neoliberal market economy.

Sirje Runge. Space II. 1977. Oil. Art Museum of Estonia

Leonhard Lapin. Woman-Machine XVII. 1977. Serigraphy. Art Museum of Estonia

What were the main challenges in reconstructing the exhibition?

The main challenges in reconstructing the exhibition were of course finding detailed documentation and countless works that had gone missing after 1975. We didn´t find all of them in the end, so making this exhibition was also a lesson of letting go and accepting that we inevitably come from the East European culture of ruptures. Sirje Runge´s painting altar is gone forever, and we can only write and think about it today, looking at the photos of the legendary Estonian photographer Jaan Klõsheiko. But the Baltic culture has, as far as we can remember, been a culture at the crossroads, and a culture of missing links. And in the end, exhibition history is a field that deals with the ephemeral, with the disappearing. And when The Society of the Estonian Art Historians and Curators was holding its seminar dedicated to exhibition history recently, it was repeatedly expressed that not everything needs to be remembered or reconstructed. Even though we live in the age of digital simulacrums where humankind is obsessed with recording and keeping everything for potential reconstruction. This obsession and illusion that we can record and reconstruct everything might not be good for our mental health. We also need to learn how to let go because the only thing we can really count on these days is that everything changes.

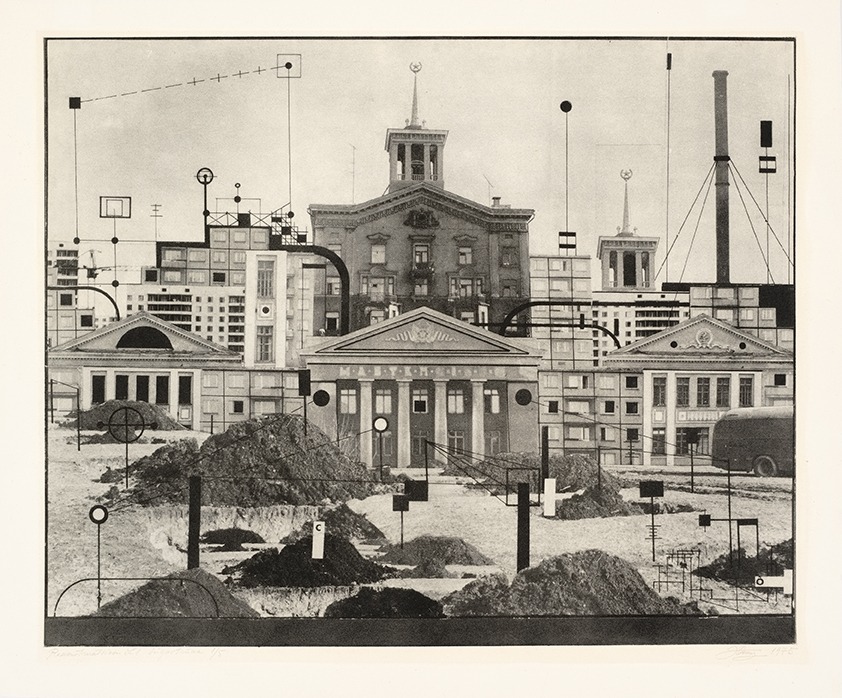

Jüri Okas. Reconstruction L1. 1975. Intaglio. Art Museum of Estonia

Did working on this exhibition change your own understanding of conceptual or experimental art from that period?

Working with this exhibition made me realize that in Estonian art of the Soviet period, there was a price to pay for no longer having separate spheres of the official and unofficial art after 1975. And this price was the big compromise that is known in Estonian art history as the aesthetic-conservative self-defense mechanism. It basically meant that the local Artists´ Union managed to tame young rebellious artists and incorporated them to the official art life. But the result was that Estonian art became pretty tamed in general until the very fall of the iron curtain, because it had locked itself to the aesthetic paradigms that wouldn´t irritate Moscow authorities, but at the same time gave artists certain autonomy to use the means of art that were prohibited during the Stalinist years. The upside of it was of course that the younger generation of artists didn´t emigrate – which left Moscow art scene pretty impoverished after the big emigration wave in the mid-1970s – but it created a kind of Golden cage for Estonian art where bold experimentation was out of the question, because even the young artists knew that with that they could bring the local art scene a lot of trouble from Moscow. So, all the former experimenters and rebels like Andres Tolts and Ando Keskküla turned to traditional painting and no bigger wave of Conceptual art even followed the Harku event. Even though Mari Kurismaa and Mari Kaljuste, who had both been present in the Harku event, realized their Lyrical Cycle. Words in Tallinn a few years later, where they left poetic statements on the pavements and houses of the city, using ephemeral materials such as snow, water and kefir.

Exhibition view of "Harku 1975. Objects, Concepts". Photography Stanislav Stepashko

Upper image: Leonhard Lapin. Poster for the art event "Harku 1975." 1975. Art Museum of Estonia