Imagery can be healthy or harmful, addictive or nutritious

An interview with Marine Tanguy, founder of MTArt Agency and originator of the notion of a “visual diet”

Marine Tanguy, founder of the London-based MTArt Agency [established in 2015, it is the first artist agency promoting visual artists as well as a creative agency that delivers exciting art-driven projects for brands, public bodies and cultural organisations], can claim authorship of the notion of a “visual diet”. She first used it publicly in a 2018 TEDx Talk in which she stated: “Imagery, like anything else, can be healthy or harmful, addictive or nutritious. And now, more so than ever, this has become a massive issue with the huge cultural impact of social media.” Tanguy’s experiment on her 24,000-follower-strong Instagram account – in which when she posted an image of her bikini-clad bottom she received 75 percent more views than usual (of which most were women) – illustrates how much people today depend on visual “fast food”, and how indifferently we treat what we see. But to quote Tanguy – what we see is what we are. The desire to change society’s visual habits, and the belief that access to art should be provided to the broadest audience possible, are at the core of MTArt Agency, as is a strong interest in supporting and developing the careers of “the most talented artists”, as it says on the agency’s webpage.

In 2018 you gave a TED Talk on how drastically visual content makes an impact on our mental health. The term “visual diet” has become like a catchphrase for you and the MTArt Agency that you founded. How did you come up with the notion of a “visual diet”, and how is it tied to MTArt?

Visuals have the power to impact all of us, whether it’s on the streets, digitally, or through campaigns. There’s a real need to be aware of the visuals that you look at every day, and also how they affect you. If you only see adverts as you walk down the streets and there’s no public art, then you may start behaving a different way. You may start consuming in a different way. And your visual thinking also changes. That was, first and foremost, the entire belief system of MTArt Agency. That’s the reason why we felt that not only do we want to build the reputation of the artist, but we also want to make sure that the arts could inspire everyone. So there are a few things that we started. We started developing the public art side of things and the digital activation side of things. I wrote a paper on the impact that public art has on people and therefore the need for it – both from the well-being side and the economical side of things. The first TED Talk happened as a result of that, and then I was asked to give a second TED Talk in Lausanne, Switzerland. They specifically wanted to discuss the visual diet, and therefore wanted to make sure that I had researched it well enough. This was a term that we had coined and therefore, in a way, owned it; it is almost like the philosophy and value statement of MTArt, but we had never expanded it through having multiple studies behind it. So when I was asked to do that second TED Talk, I made sure that I had more quantitative and qualitative studies and that I had more voices and opinions of people on the subject. After TED we did a selfie project for which we partnered up with the photographer Rankin [Mimi Gray, M&C Saatchi’s head of visual content, Marine Tanguy, and Rankin have created Visual Diet, a platform to promote a more balanced range of imagery – Ed.]. And then I have a book on the visual diet that’s due to come out towards the end of this year. So, although we don’t talk about it all the time, it is totally what we are doing as a job, every day. That makes sense.

If you only see adverts as you walk down the streets and there’s no public art, then you may start behaving a different way. You may start consuming in a different way. And your visual thinking also changes.

You mentioned that you have conducted a study on how public art can deliver wellbeing. How did you do that?

You just interview large groups of people and collect data that you then process. Then you look for correlations with people regarding their well-being and their responses towards public art, including the economic and social impacts. It’s all about having a large amount of people that you can survey from in the first place, which is what we’ve done. We simply process the data and then make conclusions from it.

Dede Bandaid. Culture fix. Public art project on Regent Street, 2021. © MTArt Agency

You have said that one’s visual diet is as important as one’s nutritional diet. We often talk about what we eat, but we do not pay attention to what we are taking in visually. American psychologist Sheldon Solomon says that art is an absolutely essential element of the human experience, and I quote: “And when we in the United States try to marginalise it, whenever we don’t have enough money, the first thing we do in education is we cut art and we cut physical education, which in the United States is often done outside. So we basically lobotomise and psychically amputate our children by divesting them early on of art, music and nature; we’re more devoted to ensuring that they become rather docile and passive meat puppets, or in other words, blind.” What do we have to do to change this habit? And what is the role of the educational system in terms of art?

The reason I love the term that we created – visual diet – is because I think first we need to bring awareness before you have any form of action afterwards. And I think many people are not conscious of the fact that visuals affect them. Up to now, visuals have been the element of the art world, which is super exclusive. So the idea that this has an effect on a mass scale is not something that’s ever been really understood up to this point. And that can completely be blamed on our system of multiple social classes dictating educational inclusion. But until now, this was something that was difficult to understand – it was often seen as something quite superficial. In the book I mentioned I’m writing, the first thing that I did was to very much cover the history of visuals. So, depending on where you’re born, what does that mean? What kind of impact do visuals have on you? And how will you develop as a person, as in, which components directly affect you?

I think many people are not conscious of the fact that visuals affect them.

The second thing, once you have self-awareness, is to have a set of tools. And I think that this is where education comes in. Much in the same way that you are taught that before you announce an opinion on something, you should always check multiple sources and all sides before you form that opinion. I think visual critical thinking should be taught in the same way. You should almost have such a sense of awareness that if you feel any kind of emotions after looking at an image, you can deconstruct why you are feeling that way – can you deconstruct why the image is pushing you to certain behaviours? That makes sense. It’s what I would call visual critical thinking (these all are terms that I’ve had to invent because they did not exist).

Can you deconstruct why the image is pushing you to certain behaviours?

I feel that it’s the same as philosophical critical thinking in which you learn that not every opinion is truthful and that every opinion needs to be measured. It’s kind of almost the same thing – learning to compare opinions, to evaluate sources, and to have “a radar” for the information that you're being given. This can start as early as very young childhood because, as you know, young kids don’t need to learn only by reading – they actually do better by learning visually. I think visual education can happen as early as you wish. We have a few schools, like Montessori, that have an emphasis on this. But it’s really unfortunate that this is not the case in mainstream education. I think in certain countries, like Germany or France, for instance, you still have access to culture, but it’s never demonstrated to you how this visual impact is everywhere, and how much as a kid (and whatever career you may eventually choose) this is very relevant for you to learn about. So that is the hope in terms of the education system.

In terms of the policy system, this is more at the government level in terms of the conversations that we’re having, such as when I spoke in Parliament here. We know that watching a screen for too long as a young child is difficult and not very healthy from a mental standpoint, and there are even certain types of content that are not really advised. My approach would be to never forbid, but we should bring that awareness to people. Like you said with comparing it to a physical diet – if I feel really crap and not really well at all mentally, I need that awareness, that knowledge, that looking at a certain type of content is going make me feel worse. So it s never removing content or censoring content. It is really just making sure that people know that there is an impact. And, of course, physically you can put on weight or lose weight. I think here it’s more about how you are feeling mentally – you will be feeling either lower or higher depending on what you consume.

Claire Luxton. Plant Yourself. Public art project of Regent Street 2021. © MTArt Agency

But it’s almost...as if you’ve stopped thinking about the art world and are thinking more about visuals. And for many people that is very difficult because up to now, the artist has been very removed from a lot of people’s lives. All types of visuals needs to be both identified and pointed out that they do have an impact. I hope that changes are coming. I think they are – we’ve always advocated for mental health understanding, and it definitely is getting better than it was ten years ago.

This can start as early as very young childhood because young kids don’t need to learn only by reading – they actually do better by learning visually. I think visual education can happen as early as you wish.

What about the pandemic? How has it changed our visual habits? How did it change yours?

What we see within the scope of the pandemic... I’m always careful of giving feedback on something that’s still undergoing. But so far we’ve done many, many public art projects. Right now in London there are nine public art projects being conducted by us. There is the exhibition right in the centre of London that is completely accessible to all [MTArt launched the public art project Plant Yourself along a 1.3-km-long stretch of Regent Street in January of this year – Ed.]. I think the role of the arts, in terms of the public sector, has really gained importance because people have realised how critical it is to integrate the arts into the high streets, into the centre of cities. The conversation around what makes the city’s landscape is quite key. And then in terms of digital, we’ve had so many amazing comments on our social media website and on the content we’re creating – people saying it’s such a nice feeling to be able to look at something that’s really inspiring and that’s really uplifting or challenging intellectually at a time when everything feels very stressful. I definitely don’t have enough data to say that overall this is excellent, but our experience of it is very positive in the sense that we have felt even more support. In fact, we’ve never been as busy as during the pandemic in terms of proving the role of the arts and having so many projects because of it.

I think the role of the arts, in terms of the public sector, has really gained importance because people have realised how critical it is to integrate the arts into the high streets, into the centre of cities. The conversation around what makes the city’s landscape is quite key.

In your TED Talk you contrasted the popularity of Kim Kardashian’s Instagram account with that of the Louvre. Kardashian’s followers outnumber those of the Louvre many times over. What does that say about today’s world, since “what we see is what we are”?

I think what it says is that our sector, the art world, has made no effort to be relatable. And on the other side, you’ve had marketing and advertising machines that have built certain types of content. But there are two sides to blame. For decades our sector hasn’t made an effort to make sure that it can approach very large audiences. And social media was very frowned upon – it was something that the art sector was very slow to get into. So this has, sadly, left more space for a certain type of content to rise. But I would blame both sides. It is always a matter of responsibility that has been shared. You know, Kim Kardashian saw an opportunity, and she is not someone to blame specifically. The marketing and advertising world she’s in is responsible for what’s happened. Equally, the art sector, by being elitist, is also responsible for her being in that position. So the two sectors have basically paid the price of what they have created. And what they have created and the type of content that we see on these platforms is, sadly, not as diversified nor as healthy as we would like it to be.

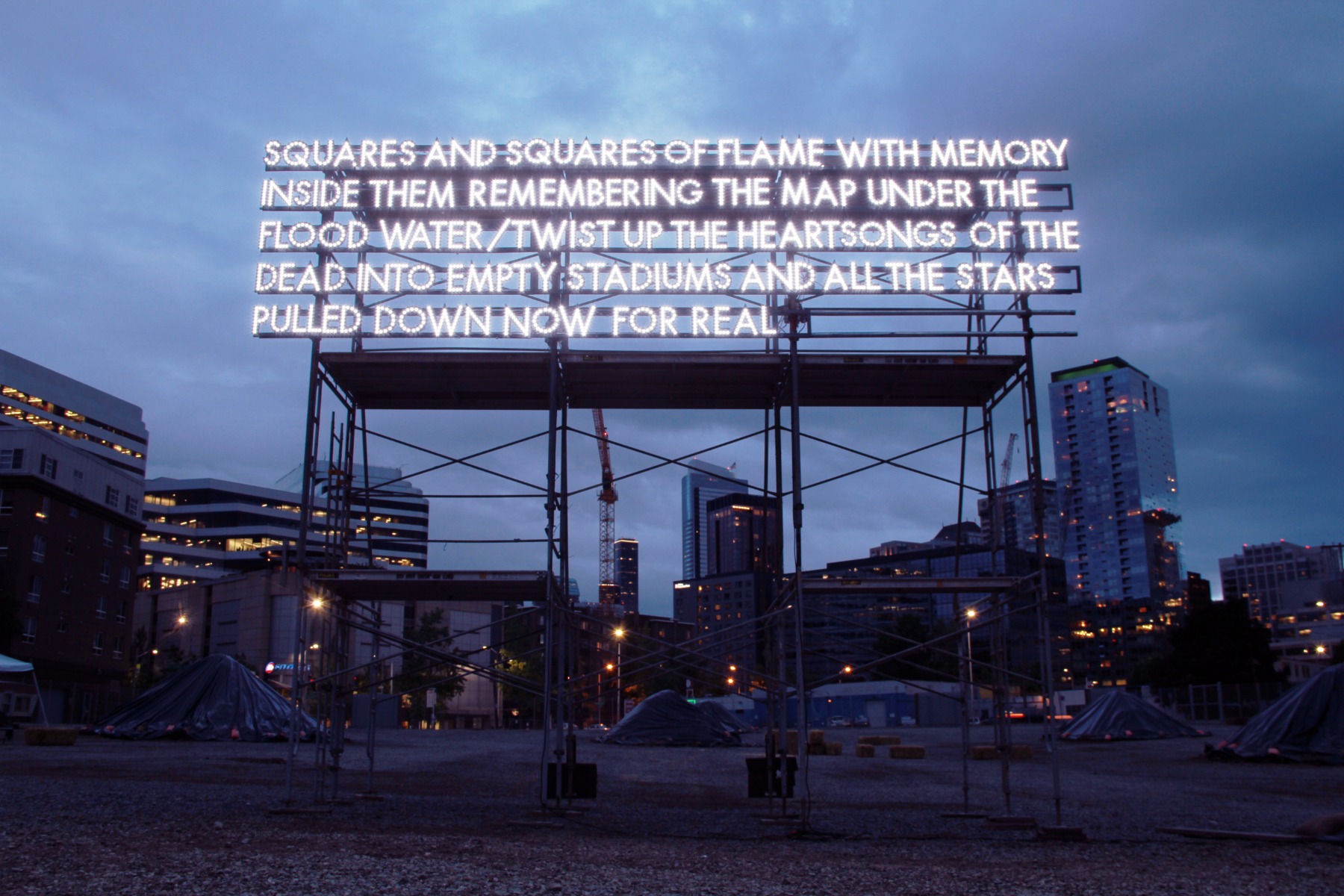

Robert Montgomery. The title is the one of the poem, neons, 2017. © Robert Montgomery

During the pandemic we used to say that art can heal us. But these are just words if people do not know how to look at art to find comfort, e.g. to seek out it’s depth, or to become fascinated with it. What is the most important thing in this process of looking? Art critic Jerry Saltz says that art is something to experience, and not to understand. In his book The Value of Art, Michael Findley talks about the necessity to mute our right-brain impulses that are responsible for logic and analytics. He says that it’s possible that certain drugs, particularly so-called hallucinogenic drugs, can perform this function. He is not advocating drug use, but he does suggest that to access the essential value of art, it’s important to turn the volume down on the facts about the art piece and just sit with it for at least as much time as it takes to read your newspaper or favourite blog. What is your suggestion on how one can discover this power of art?

I’m not really in agreement with the assumption that people do not know how to look at art. The art sector has made sure that people were not included, that they were not a part of it. So it’s normal that they’re not interested in something that’s not including them; it’s a very human response to be attracted to things that include you. That’s why I think that everyone has the same capacity to be able to look at art if they are included, communicated to, and made aware of it. The art world is paying the price of not having been inclusive. And it is, sadly, an expensive price because it’s not a very clever strategy. It might have worked on a few people. They might have paid a lot of money for certain works. But in reality, anything that must be on a big scale requires a lot more clever strategy than anything on a small scale. So, it’s not the fault of people. It’s is definitely the fault of the sector – if they haven’t made themselves relatable, then they’re paying the price for that. That’s just the best way to say it. I wouldn’t put people into that. I think it is also very arrogant in terms of not understanding the multiple dynamics involved – from access to education levels, to family backgrounds, to privileges, etc. – which are the reason why these people are not looking at art in the same way as others may be.

The art sector has made sure that people were not included, that they were not a part of it. So it’s normal that they’re not interested in something that’s not including them; it’s a very human response to be attracted to things that include you.

But the museums in Europe’s capitals are full of people. Lines would even form when blockbuster works were being shown...

I think there are two things behind that: one, museum demographics are not as diverse as we would want them when compared to a football stadium or the numbers watching the Oscar ceremony at home on TV. The museums are not filling up with loads of people. They are, of course, busy, but they’re not as relevant as any other talent or cultural sector venues. Compare the numbers going to the Tate and those watching the Oscars on TV.

The second reason why museums are so heavily impacted is because up to now, it’s been an issue of tourism. Either you come from a lovely background in which your parents took you to art museums, or you’re a tourist visiting a city that is not your own. For example, if you’re visiting London, you need to go and see the Tate. It simply hasn’t been part of the daily existence of most people. It hasn’t been made understood that this was meant to be part of that existence. And again, if you look at education, art education is mostly being given in private schools and not at state schools. You can’t expect people who haven't had the education to have the habit of the very wealthy of thinking: Oh, I know, I’ll go to go to a museum on Sunday. It is silly because if all of this was actually done, museums would be much more filled. You can’t expect people to take the initiative if it’s not even on their radar. That’s the reason, again, why I would be careful with numbers. They are busy, but they’re nowhere near the numbers that the entertainment sectors see. It’s very small in comparison.

Art education is mostly being given in private schools and not at state schools. You can’t expect people who haven't had the education to have the habit of the very wealthy of thinking: Oh, I know, I’ll go to go to a museum on Sunday.

It’s a multilevel system that, if it worked properly, could bring about radical change...

Our public art projects have been seen by millions of people, and they are not the people who would have gone to the museums. Our digital campaigns are the same. When our artists can, they work in collaboration with other creatives, no matter if it’s music, film, anything; they’re also seen by demographics who would never normally come to the sector. And then, of course, you have government education policies, too. But I think if one were to count all people that have seen the public art projects that we have organised, it’s more than the numbers that will go to the Tate. And they are commuters, they are locals, they are workers. I do think you can widen the demographics if you try and find people where they are and if you try to interest them where they already are.

Leo Caillard. Neon Laocoon, chromed marbled resin, neons, LED, 2020

Do you remember your first important art experience? When did you first understand the power of art?

I think my first art experience came quite late – I was 18 and I was at the Louvre, where I saw The Raft of the Medusa by Géricault. I was at university at that point. It made a big impact on me because I felt the emotion, the political cause; and the technique was incredible. Those three combined can be very dramatic. It’s also a pretty large painting, and I think a very important symbol for the Louvre as well.

But I wouldn’t separate the importance of the arts from the importance of visuals, which is something that I realised much earlier. When I was younger and not feeling well, I would go to the sea. I was five or six when I understood that this is a toolkit you can use to make you feel better – changing your environment. So I think that I was aware of the impact of visuals much earlier, and I didn’t need to wait for art to show me that. We want to impact everyday life; we don’t just want to wait for that perfect art experience. We want to make sure that we get you as early as possible and that you are impacted positively. For me, growing up in a beautiful place by the seaside meant that I knew what is very beautiful and I could use that when I was not feeling very well. So it was any experience that was creative, that was visual, that impacted me.

When I was younger and not feeling well, I would go to the sea. I was five or six when I understood that this is a toolkit you can use to make you feel better – changing your environment.

Yesterday I spoke to one of my friends who is a curator and he said an interesting thing: perhaps contemporary art is not the right space where people should be looking for harmony because it has become an industry of fashionable topics and has lost the desire to look inside of us, that is, to talk about existential questions. As Bridget Riley said, and I’m paraphrasing, a work is not worth looking at if it does not function on the high level deemed necessary to convey spirit, mood and feelings.

That’s a very large question that requires a much longer answer, but when you think about the first meaning of art, it was commissioned by the Church in the 14th century. Obviously, there were cave paintings, but proper collectors of art, the proper sector, started with the Church, which basically made people believe in things. I’m not sure this was really meant to describe existential details, nor was it beauty-orientated. It was like an advertisement for the Church. It was like the birth of advertising versus religion. I think if you look through history, whether it’s the Medicis, whether it’s the commissioning of art, whether art is being used politically, especially in times of revolution... It’s always been the case that other things have been tied to art. For instance, the French Revolution was very tied to art. The Russian Revolution in the 20th century was exactly the same. And politics and art have always walked hand-in-hand because they usually are among the pillars of societies.

I do think people are waking up to discussing topical subjects. For example, The Raft of the Medusa by Géricault is about a shipwreck where the very wealthy were able to escape on boats but the rest had to die on a raft from starvation. That’s a very topical subject. And it was on the front page of the papers at that time. The incident was precisely an issue of class, and could be completely put side by side with the conversation that is happening right now concerning race and class. So I don’t see how this is different. I think art does have to take a position. I think it’s a language, and what is nice is that, like language, it can include as many people, things, and topics as we put into it. So if someone says: I want to just look at beauty, then you can have that within the language. But if someone says that they want the language to discuss topics that are really relevant to them, they should also be able to be a part of that. That’s the core of a language. It should be inclusive of all types of thinking. Contemporary art is just the language of the contemporary times. There’s no single way to define it. There are hundreds of millions of images. For me, as long as it’s a language that embodies everyone, then that’s fine. You can go into a type of contemporary art that you like, and just as well I can go into a type that I like.

You founded the MTArt Agency, but before that you had a gallery. Why did you switch from the gallery format to an agency?

I’ve been in the art world for 12 years. I was first a gallery manager when I was 21, and I opened the gallery in Los Angeles when I was 23. There I met this incredible man, Michael Ovitz, who created CAA (Creative Artists Agency); he is one of the biggest art collectors in the States and someone who has really been rethinking the impact of the film and cultural sectors. He was behind Jurassic Park, Steven Spielberg, Tom Cruise... and he saw that whole scene. And when Michael would talk about how he was supporting talent, how he was impacting the cultural conversation, how he was packaging talent and ideas together, I just felt that this was exactly the job I wanted to do. Now we are building a kind of “CAA for the art world”. It’s the same business, the same course.

Title image: Marine Tanguy, founder of MTArt Agency and originator of the notion of a “visual diet”