I am absolutely happy with this honesty

An interview with the curator of the 2nd Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art, Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel

‘On 14 March, two months before the planned opening of and suddenly it all blossoms, as the COVID-19 pandemic was rapidly spreading, the decision to suspend the preparation of the show had to be taken, to freeze the installation and to announce its indefinite postponement.’ This is the opening paragraph of the text written by the curator of the 2nd Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art (RIBOCA2), Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel, for the guide to the Biennial which is nevertheless about to open just now. Admittedly, it did not happen in late May as originally scheduled; the Biennial will be launched on 20 August and take place for just three weeks. However, instead of disappearing without leaving a trace, it will provide an opportunity to view the exhibition to everybody who, due to various reasons stemming from the current situation, are unable to come to Riga. This opportunity will take the shape of a feature documentary shot over the course of these three weeks.

The Riga Biennial is taking place after all ‒ and it is, of course, a gesture of not surrendering in the face of circumstances and the result of some very strong teamwork during the preparation stage. Many of the participating artists were also forced to reinvent their original ideas, adapting them to the restrictions of the current situation with its limited possibilities of production and transportation. Rebecca, an experienced curator who has mounted a number of key exhibitions at the Paris Palais de Tokyo over the course of several years, unexpectedly encountered a situation of lockdown and a pandemic ‒ and did not allow it to intimidate her. A young mother whose daughter was born just last year, Rebecca, working with the commissioner of the Biennial, Agniya Mirgorodskaya, and the whole RIBOCA team, was forced to assume responsibility for an unpredictable situation. In this sense, she is a born fighter – and, perhaps, the perfect curator for a biennial taking place in this year of 2020, so difficult and so vital for the foreseeable future.

Venue of RIBOCA2 - Andrejsala

‘The Biennial had thus been proposed as an alternative to the torrent of hopeless narratives, taking the notion of “re-enchantment” as a frame for building desirable presents and futures. Conceived as a call for the radical re-evaluation of the values of a predatory, exploitative and destructive society, this is a statement against cynicism and political despair, where the end of a world does not mean the end of the world. [..] Rather than postponing the Biennial until the return of “normality”, we deliberately chose to open for the final weeks of its original dates, accepting the impossibility of our previous plans and constructing the project within this new reality. The exhibition that has been built is thus somewhere between a ruin and a renovation site, mirroring the current state of the world, a liminal and floating space and time,’ says Rebecca in her curatorial concept.

Last year Arterritory.com already published an extensive and interesting interview with Rebecca, in which she spoke about her background, the environment in which she grew up, her first curatorial efforts, and her vision for the 2nd Riga Biennial. In this latest conversation, which took place literally a week before the opening, we focused on the reality of the actual RIBOCA2 and the unexpected and powerful ways in which the original concept of the event resonated with what has happened and is still happening in 2020.

Ugo Rondinone, Life Time, 2019. Neon, acrylic glass, translucent foil, aluminium, 248 x 752 cm, courtesy of Studio Rondinone.

How are you feeling right now ‒ in mid-August, half-way through the year that has instilled into us a distinct sense of uncertainty and unpredictability?

These are very mixed feelings… From its inception, the subject we had chosen for this edition of the Biennial was ‘The End of a World’. And we saw our task in showing how art could help us propose some kind of new scenarios and alternative visions of how we felt, acted and built our relationships. Because there has been this sense that the planet is in agony for a number of years now. It was impossible to go on using the existing system. The relentless growth of production and consumption totally failed to take into consideration the realities of all the other beings, the non-humans, from whom we have been trying to distance ourselves culturally.

When the pandemic broke out, it became a striking illustration to how this whole super-powerful civilisation could be brought to its knees by the tiniest living creature on our planet. This is bringing us back to Earth and cutting the ground from under the feet of the whole idea of human exclusivity. We are all part of something much bigger, and we only mean something together.

When the pandemic broke out, it became a striking illustration to how this whole super-powerful civilisation could be brought to its knees by the tiniest living creature on our planet.

When countries started closing their borders and lockdown was introduced, we had already been actively working on the exhibition. At that point, practically almost near the finishing line, we were forced to bring the process to a halt and freeze the whole thing. And yet, exactly for the reason that the exhibition had been intended as a reflection on the subject of how to accept uncertainty, how to accept that there is a limit to our control and our power, the very ethics of the project was guiding us toward the idea that it had to be realized and could not be suspended indefinitely.

When I finally found myself on the exhibition grounds in Andrejsala a couple of days ago, after weeks and weeks of Zoom conferences and discussions with the artists and the team, it was an incredible feeling. I have really fallen in love with the location; it has grown to mean a lot to me. But I also thought about the fact that the Biennial was supposed to welcome thousands of VIP guests from all over the world. Because that’s what the model of a biennial is: it is a giant international event that brings together a huge number of guests and participants. I would, of course, be only too happy to see all of my friends and everybody who came here. But it would not correlate too well with the new model that I wanted to introduce and present in the framework of this exhibition. During the final weeks of working on RIBOCA2, I was becoming aware that the Biennial is getting closer and closer to what it actually should be… and who it should be for: the people of Riga, Latvia, and its Baltic neighbours.

Furthermore, we are opening up 200 000 square metres of the Andrejsala territory, ‘returning’ them to the city and its residents. Initially we had planned to provide them with this opportunity for four months; we are now counting on a mere three weeks. But we are doing as much as we can. The territory is still populated by ‘ghosts’ for us – the absence of all the works we did not manage to bring here. And we accept this and do not try and hide from the fact. So, when you visit the place, you may also hear a kind of ‘scream’ ‒ the wailing of all the things that could not materialize, could not be born.

We are opening up 200 000 square metres of the Andrejsala territory, ‘returning’ them to the city and its residents.

And another thing that is extremely important for me as a curator ‒ it is a totally obvious connection with the reality outside the boundaries of the Biennial. Museums and exhibitions are normally like islands of stability and detachment, a kind of different world that is not directly linked to everything that is going on in our lives. It is going to be different here. We are going to show photocopies instead of original drawings; some spaces will simply remain empty while others will be jam-packed with works ‒ because they were created in Riga, which means that we can show them. At that, I still feel a certain nostalgia or sadness because, while I am proud of what we have eventually come up with, it is nevertheless not quite the exhibition I was dreaming and fantasizing of for a number of years. Nevertheless, I am absolutely happy with the honesty that has become an integral part of the exhibition. As I am with the fact that, when we found ourselves facing this incredibly difficult challenge, the whole team ‒ to which I am so very grateful ‒ kept fighting without sparing themselves for us to be able to open the exhibition no matter what; and it came true. Everything that went on inside the team, all the effort, solidarity and ethics that remain behind the scenes, matter as much, in fact, as everything that will be shown at the exhibition.

Pages from RIBOCA2 guide with crossed out, added and highlighted text

Moreover, the exhibition will now find its continuation in the shape of a feature documentary. And we found that it was a decision that ideally suited this time ‒ to transform the exhibition into a film that gives voice to the present situation with its uncertainties, desires, disappointments. And no matter how strong these disappointments may be, the key idea of the exhibition is ‒ never give up. Never give up our most essential desires, dreams and search for the most correct, the best way of being human.

The key idea of the exhibition is ‒ never give up. Never give up our most essential desires, dreams and search for the most correct, the best way of being human.

These ‘ghosts’ that you mention, the skeleton of unrealized works, is excellently displayed in the catalogue/guide to the Biennial, where the original text has been preserved. In those places where it no longer corresponds to reality, it has been crossed out and new paragraphs, printed in a different colour, have been added. This creates a very graphic and symbolic co-existence of two realities. Something which can also be viewed as a model of our current state, in which we all live with all these aborted plans looming in sight, calling out to us from late 2019 or early 2020. We sort of exist between these two worlds. And the Riga Biennial is, of course, also an excellent illustration of the situation ‒ and to the human effort to accept a change of plans and always find an alternative, to find a way out.

When we realized that the whole thing was collapsing around us, we called all the participating artists of the Biennial, and with many of them we were able to find ways of transforming/adapting their works or the intended ways of presentation. And it was complete understanding and cooperation on their part. We discussed these things with Ugo Rondinone, with Marguerite Humeau, and with many others. And I am incredibly grateful to them all; it actually means that the artists have come up with practically twice the number of works as intended for the Biennial ‒ if we take both the original and new ideas into account. Problems gradually started to transform into solutions, and I really think that artists, of all people, are the ones who are capable of that. And it was a kind of practical demonstration, a mass demonstration of this capability ‒ of what we are able to get done right here and now.

Problems gradually started to transform into solutions, and I really think that artists, of all people, are the ones who are capable of that.

And Andrejsala is a very important place in this sense ‒ because of all these layers of history that are present here, because of all the marks left by time. Andrejsala was originally born out of the human desire to control nature: it was a result of all these piers and causeways next to Riga that this island emerged. The territory became the object of various military and industrial designs; later, in the Soviet era, first commercial, then cultural projects were attempted, but as time went by, they, too, slowly disintegrated. To me, Andrejsala is a metaphor for the same problems we have been encountering globally. The soil is saturated with toxic waste; the buildings inherited from the industrial port are too enormous. It is exactly for this reason that we chose the warehouse building as the main venue of the Biennial: surreally gigantic, it looks as if it had not been built for people, for the human scale. And at the same time, it seems to invite you to go for a walk on its premises; it invites you to slow down and instils the sort of serenity you need to reflect on what we could do with this place and that kind of legacy today. And the exhibition also invites you to a meditation in the form of a walk. Many philosophers have commented on the importance of walks, Nietzsche being one of them ‒ on the ways in which the rhythm of the human body integrates with other kinds of rhythms: the seasonal rhythms, the rhythm of nature with its sounds and smells. And that is the experience we want to offer to our audience.

To me, this sense of a point between different eras, a point of uncertainty, is also directly linked with the extremely strong programme of online talks and conversations presented in the public programme of the Biennial. And it was exactly this state of not knowing for sure, of uncertainty, that, for instance, the anthropologist Tobias Rees spoke about; I also had the opportunity to discuss this subject with him in an interview… It seems very important that RIBOCA2 offers not just a solid artistic statement but also creates an atmosphere of rethinking certain key elements of contemporary existence.

We are all very lucky to have people among us who are wonderfully equipped for tackling this kind of rethinking. To me, it was incredibly important to recognize these voices and give them the opportunity to be heard. The associate curator of the public programmes, Sofia Lemos, has done a huge and very important job to make it happen. I think of the Biennial in terms of the Glossary we came up with, a compilation of key words and concepts that have been discussed during our series of online talks. It is a joint project by people who work with the corporeity of things ‒ artists, and those who deal with the world of the intangible ‒ thinkers, philosophers.

It is very obvious how much contemporary people are consumed by the ideas of healthy living and healing our bodies, but I still think that our minds need to be healed just as badly. In his reflections on ecology, Félix Guattari says that nothing will ever change until we start dealing with the primary ecology ‒ mental ecology. Until we learn to understand the direct consequences of our own actions. I can name some very simple and mundane examples, but these are the choices we are making at every step: do you or don’t you eat meat; how much time do you spend showering and how much water do you use up doing that; how many plane trips do you make every year. Everything we do has some very specific consequences. At that, it is important that we don’t view it as a problem but rather an inspiring sign that we matter and our actions matter. And everything we do makes a difference.

It is very obvious how much contemporary people are consumed by the ideas of healthy living and healing our bodies, but I still think that our minds need to be healed just as badly.

Another thing that is important here is an interest in various irrational things and concepts that are more common in the Asian or African worlds than they are in the West. It is all about the beauty of ignorance, about the play of reason, the boldness and unexpectedness of hypotheses. At a time when everything around us is collapsing, it may become a starting point for rethinking our relationship with everything around us. Every week philosophers, thinkers and poets give their talks, providing us with food for thought, unfolding their versions of these scenarios in front of us. And that is exactly what the Biennial is all about ‒ that is what it will be talking about to its local audience first, and then, in the form of a film, to international audiences.

Hanne Lippard, from series Contactless

Perhaps you could expound on the idea behind the film and the decisions you have made with the director, Dāvis Sīmanis?

Basically, I already arranged the actual exhibition in a way that is somewhat reminiscent of a film. Or an odyssey. There is a prologue, Contactless by Hanne Lippard; these are poems on the contactless relationships in our current reality ‒ eight texts displayed on billboards that you see as you drive into Andrejsala. Traces of these poems, like pieces of a puzzle, will also be scattered all over the city. The actual texts comment on the speed at which everything is moving, seemingly to make a contact ‒ and yet it does not happen. In fact, the opposite takes place: the distance between us grows exponentially. And then you walk through the gate and find yourself in this detached and very special territory, in Andrejsala, which seems to be floating in time and space. The camera will basically be following the footsteps of a hypothetical visitor. It will be like a private journey through the works and the performances. Cinematographically, of course, there is a lot to work with, because Andrejsala in itself is quite reminiscent of a Tarkovskian landscape. It is very cinematographic, visually.

And so you walk through the gate and find yourself in front of the hangar. It should be noted that the journey is accompanied by a voice-over which, incidentally, does not provide a documentary-style commentary on the works. It does not say: ‘This is a piece by Hanne Lippard; it is entitled so-and-so.’ No. What it does instead is ask/pronounce questions regarding this contactless existence and its meanings.

And then comes Life Time, a new work by Ugo Rondinone ‒ a sign that was cut out of plywood and painted. The artist came up with this idea when we were forced to find a replacement for the originally planned neon rainbow poems, each of which was like a rainbow-shaped aphorism. That is also an important question ‒ what we can make room for during our lifetime, or, a question of life that is so much older and bigger than us. Then you are greeted by Bridget Polk and her performance dedicated to balancing stones. This piece speaks about a search for impossible equilibrium, and it is created out of materials found near the exhibition area. It is rubble from the grounds of the Biennial and stones that have been left over from several demolished buildings in the city. The balance she has found seems, at first glance, impossible and contrary to the laws of physics. And yet it works and, as a result, these sort of vertical sculptures are created. We have no idea how long these objects are going to stay intact, how long they are going to exist. They can fall apart in two seconds, two weeks, two months, two years… It is an incredible metaphor of our current state of existence: you are building some kinds of things, and yet you have no idea how long they are going to exist. Then they fall apart, and you start building them all over again. It is like a Sisyphus of our time, performing his labour with the material layers of Riga. At this point, the narrator’s voice will be speaking to you about things and ideas that deal with building, constructing and demolishing. And then you encounter the work of Heinz Frank, who proposes rebuilding the world the way that children see it. Heinz has published an incredible book for architects, inviting them to design buildings that correspond to the feelings and outlook of children. It means letting go of classicism, this passion for symmetry, and taking up something much less elegant, much more colourful and cheerful…

Bridget Polk’s performance work and installation of balancing rocks. Phото: Tomas Majors

I am, of course, not going to go through the whole odyssey with its 47 works now, but every time it will be a piece that poses a question, and then the next work will sort of continue the theme while examining it from a completely different angle. And the film emerging in our mind (and, in parallel, ‘on screen’) can be considered a kind of manifesto, a manifesto for 2020 ‒ dealing with questions of what is this world, what are these images around us, who are we, and where are we heading. And I think that artists can play a very very important role in these reflections on our perspectives, because I do not see anything similar taking place in politics or economics. There is no discussion of this level on perspectives; there is a lack of this interesting and thought-provoking approach typical for artists. At this time of crisis, the importance of art is only growing more obvious.

At this time of crisis, the importance of art is only growing more obvious.

So the film will be like a cinematographic walk accompanied by a narrator’s voice and his philosophical commentary. There will be no interviews with the artists, and form-wise, it is something…

...something akin to the films by Chris Marker. You are constantly guided by this voice, invited to go farther and farther. And to me, this voice is how today sounds, how our zeitgeist sounds. The film will be shot as a united, uninterrupted sequence as much as possible, as drifting through the exhibition. And the exhibition concludes with Ocean II Ocean by Cyprien Gaillard. It is an incredible video that shows the journey of a material – fossilized seashells – from coral reefs to the panelling of Russian metro stations; whereas the opposite happens to written-off train carriages from the New York underground ‒ they end up discarded on the ocean floor. This will be the final of this lengthy narrative about ourselves and our attempts to make sense of the ways we exist in this world. But all kinds of different performers will also be involved. For instance, the dogs in Dora Budor’s piece. She was originally interested in the subject of film extras – an anonymous, faceless crowd that is, at the same time, extremely important for the story because it embodies the role of collective emotions: fear, horror, excitement. And she wanted to move these extras from the background to the foreground; according to her idea, some 50‒70 people should have taken part, performing their own special choreography. Due to the current restrictions and challenges, she decided to replace people with dogs. We should remember that dogs often took the place of humans in Soviet scientific experiments and space programmes. And now something similar is taking place here.

Work of Lina Lapelytė and Mantas Petraitis. Visualisation.

We should also mention performances by Lina Lapelytė, who has created an extensive installation entitled Currents in which over two thousand pine logs make up an island floating in the water next to the main venue of the Biennial; she will present her performances there. Then there is the performance by Nina Beier, Total Loss, featuring pregnant women who will, at intervals, drive over in Range Rovers to feed the local cats by pouring milk on overturned marble lions. It is both a dialogue with the ‘indigenous’ residents of the locality and an invitation to reflect on the subject of ‘milk’ and feeding. So you see that there will be a lot going on, almost like a theatre performance. And this voice will guide us to, I believe, a somewhat surreal feeling in the end, although we are going to see completely real things. This fluctuation, this ambivalence of the relationship between the rational and the irrational, is generally an important part of today, and it will be reflected in the film.

We should remember that dogs often took the place of humans in Soviet scientific experiments and space programmes. And now something similar is taking place here.

The original concept of the Biennial was centred around the notion of re-enchantment, finding a new enchantment with the world. Has it changed during the development stage of the Biennial? And what are the ways in which the works by Baltic artists in particular interact with this concept?

The re-enchantment idea is still present, and the concept has never been as alive as it is now: it is taking on flesh. Etymologically, re-enchantment is derived from ‘being enchanted’ ‒ a state where you are hearing voices, they are putting you under a spell, transforming you. To me, it is a very important notion that speaks of the necessity to listen to the voices which we haven’t been prepared to hear or which have been constantly muted. And of the potential to see magic around us once again. The world has lost its sense of wonder; everything is subject to control and assimilation. Including the utilization of the Earth’s resources, spurred on by the capitalist economy. How long can we go on extracting everything from the Earth and transforming everything to meet our needs, as long as it brings profit? These relationships are built in such a wrong way, and they are harmful to ourselves ‒ and I mean mostly women and people with different physical abilities, or people of colour. They ignore everybody who does not conform to the norm, which is predominantly white and male.

How can we reimagine these relationships to make them much more inclusive and exhaustive? Re-enchantment is largely about a possibility of listening to a diversity of voices around us and trying to find harmony in this chorus ‒ instead of ranking everything according to its power and influence.

In this sense, I was very inspired by the Baltic context, particularly when I first came here to do some research and choose a conceptual direction ‒ when I spoke to various researchers, when I visited the National Library and explored the dainas, the traditional form of Baltic folk texts, when I took part in a celebration of the Midsummer Night festivities. Here in Latvia such a hugely significant role is still enjoyed by the culture of voices and singing, which both defines the relationship with one’s body and teaches to hear other voices, other rhythms. This type of skill no longer exists in France and French culture. This sensitivity, this regard has long been completely annihilated. These things are written out of contemporaneity and filed under ‘folklore’. I absolutely hate the term, because for me it is a label that signifies covert contempt, a diminishing of importance, and attempts to sideline. It is as unacceptable a category as, say, ‘outsider art’. The world we have built is based on this kind of categories throughout. We must be super sensitive regarding them, constantly questioning or giving up this sort of categorization.

Re-enchantment is largely about a possibility of listening to a diversity of voices around us and trying to find harmony in this chorus ‒ instead of ranking everything according to its power and influence.

And that is why I refer to everyone taking part in the Biennial as participants, without dividing them into artists, philosophers, thinkers or people like Bridget Polk, who has never called herself an artist, instead looking at her practices as meditation...or Vija Eniņa, whose speciality is medicinal plants.

This concept is represented by many artists from the Baltic countries. For instance, the Lithuanian artist Lina Lapelytė works with an ancient tradition. Since time immemorial, rafters used to transport timber down the river. Men built giant rafts while singing their songs about their own skills and strength. Lina will invite women to this island of logs that, thanks to her, will appear in the river near Andrejsala, and they will be singing completely different songs ‒ about different kinds of relationships that can be built with the world and these floating logs. Then we should also mention the Latvian duo IevaKrish and their work entitled Polemic of Two Metrics ‒ a sound and sculptural installation creating spatial, temporal and sonic choreography. It is centred around a huge sculpture suspended from the ceiling, representing a puzuris ‒ the traditional Latvian and Lithuanian mobile construction consisting of a double pyramid made of straw and revolving on its own axis. The puzuris is credited with supernatural qualities: it is believed that by spinning it consumes negative energy; it is like a symbol of the celestial in a domestic setup. The huge puzuris made by IevaKrish will rotate and cast a shadow, like a shadow of the unknown, and the bodies of the dancers will create an intricate interplay with this shadow, which will be changing under the influence of air and wind ‒ the elements that we cannot influence. Meanwhile, Kristaps Ancāns continues his practice of building machines that go absolutely beyond our expectations of such mechanisms and their ways of behaving. Can machines develop feelings and desires, things that are supposed to be an exclusively human prerogative? That is the question Ancāns is asking in his installation called What Do I Dream About? The machines perform automatic movements that seem completely surreal and not intended to meet any objectives of their production.

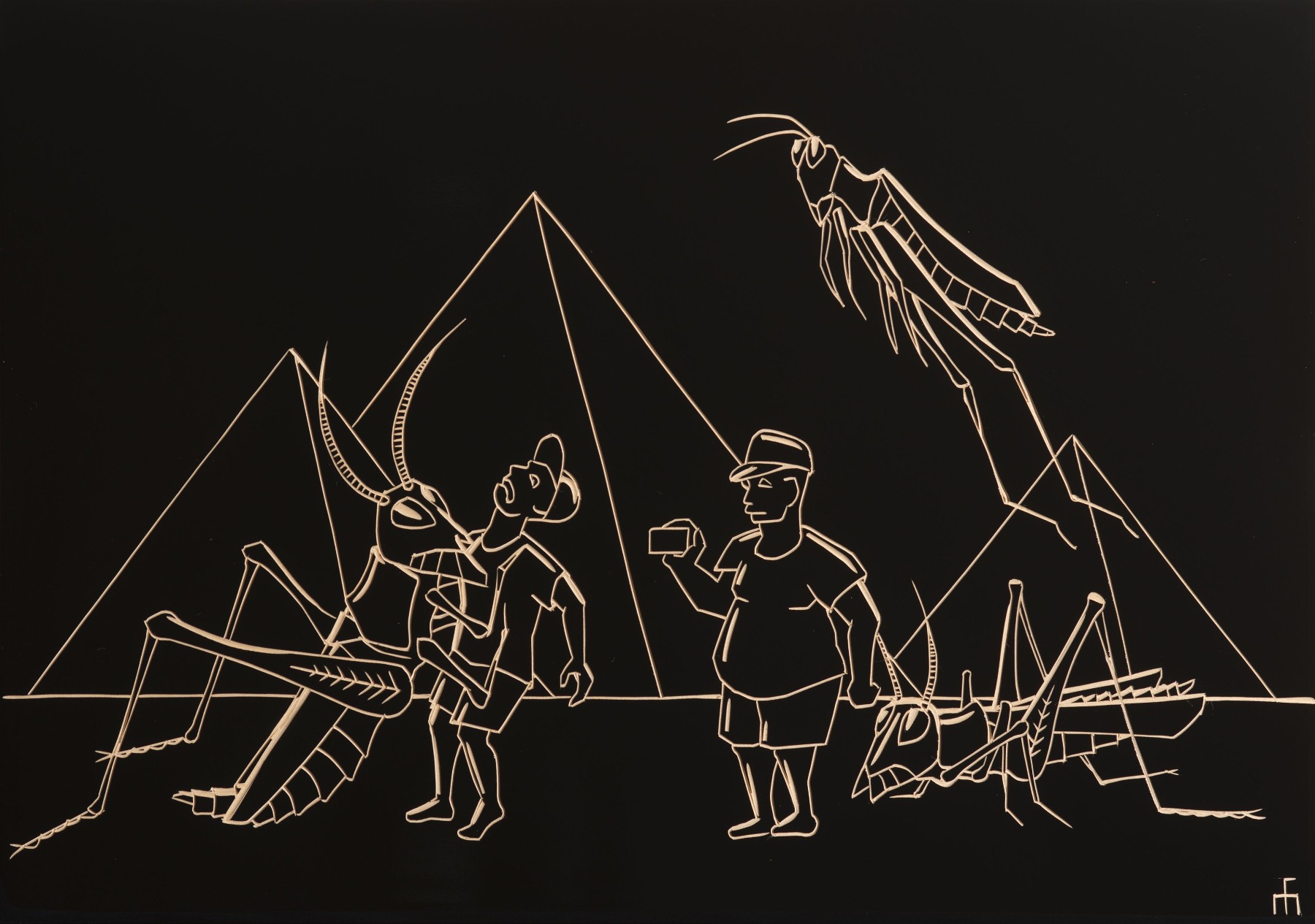

Miķelis Fišers. Giant Grasshoppers Massacre Tourists by the Pyramids of Giza, 2017 Polished paint and carving on wood, 21 × 29.5 cm Courtesy of the artist

Miķelis Fišers is an artist who has always been sensitive to questions of a dystopian future and science fiction. To me, science fiction is super important. It is one of the most marvellous tools for expanding our spiritual world. Donna Haraway describes it wonderfully as a space for projections and hypotheses, existing completely outside any kind of norms and regulations. You can express yourself freely in this space, creating any kind of alternatives to the existing world. That is why I thought it would be interesting to involve Miķelis as a participating artist. And he chose, somewhat unusually for himself, the medium of sculpture. In-Finity by Fišers constitutes a triangular sculpture made of balloons that keep inflating and deflating and finally bursting chaotically, provoking a variety of reactions ‒ from surprise and fright to laughter. There is this tension, an analogy of the fragility of the world, and a feeling that something is about to happen at any moment now, whether we want it to or not… And, of course, we must mention Vija Eniņa and her medicinal plants that were sown and now are freely growing all over the grounds of the Biennial like an illustration of its motto, borrowed from a poem by Māra Zālīte: and suddenly it all blossoms.

To me, science fiction is super important. It is one of the most marvellous tools for expanding our spiritual world.

Other artists from the Baltic states are contributing to the Biennial as well, but all of them, in one way or another, are calling for a renewal of our sensitivity toward the world and speaking of all the different ways in which we can live and the huge potential that exists in this sense. And that, on the whole, is exactly the message of the Biennial as it was conceived, as it was realized, and as it will be presented to the visitors arriving on 20 August.

Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel