What artists are doing now. Artist duo Walter Martin and Paloma Munoz in Spain

An inspiration and mutual solidarity project for the creative industries

In the current situation, clearly our top priority is to take care of our families, friends and fellow citizens. Nevertheless, while public life is paralyzed and museums, galleries and cultural institutions are closed, in many of us neither the urge to work nor the creative spark have disappeared. In fact, quite the opposite is happening in what is turning out to be a time that befits self-reflection and the generation of new ideas for the future. Although we are at home and self-isolating, we all – artists, creatives and Arterritory.com – continue to work, think and feel. As a sort of gesture of inspiration and ‘remote’ mutual solidarity, we have launched the project titled What Artists Are Doing Now, with the aim of showing and affirming that neither life nor creative energy are coming to a stop during this crisis. We have invited artists from all over the world to send us a short video or photo story illustrating what they are doing, what they are thinking, and how they are feeling during this time of crisis and self-isolation. All artist stories will be published on Arterritory.com and on our Instagram and Facebook accounts. We at Arterritory.com are convinced that creativity and positive emotions are good for the immune system and just might help us better navigate through these difficult times.

From their home in El Campello, Alicante artist duo Walter Martin and Paloma Muñoz answers a short questionnaire by Arterritory.com:

Are you working on any projects right now in your studio? If so, could you briefly describe them?

Walter: In our lockdown location here in the southeast coast of Spain, we have very limited studio resources. We do have a lot of books though and so after a couple of weeks in lockdown we started working on a photo series based on the books in our library. We are not sure if it qualifies as art or is just an exercise to relieve anxiety. But it feels right for the moment. Maybe we are developing our first body of work for a new era of improvisation and scant production values. If so, let’s call it: Neo-Povera. We photograph different arrangements of the books and then change the titles in Photoshop. Our invented titles are dark and goofy but reality based. The book arrangements are themed. One is about food or the lack of it, another is about things one does in confinement to pass the time, another works with the implications of too much time alone in the same small space.

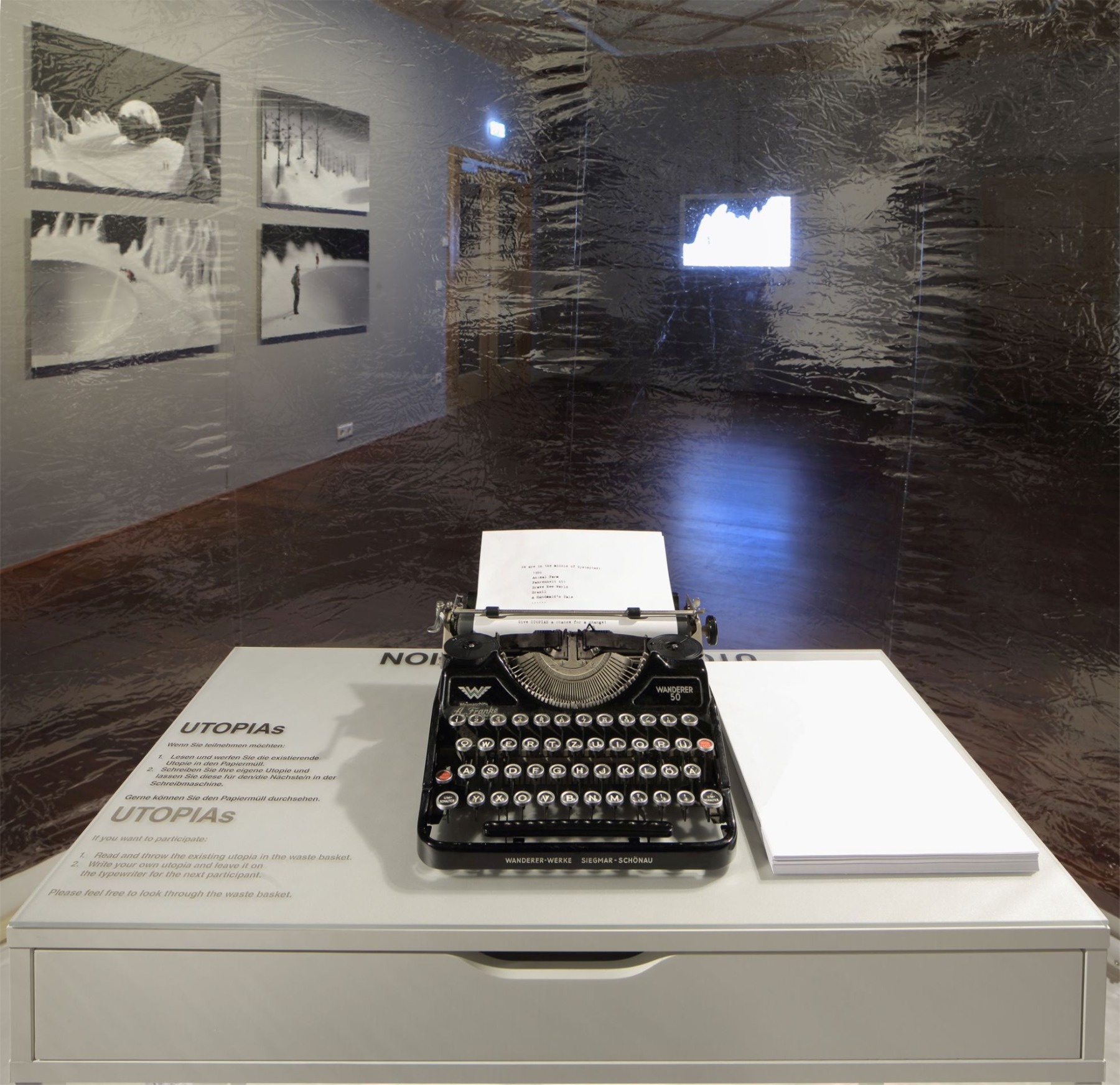

Utopia Work Station by Walter Martin & Paloma Muñoz / Courtesy Museum der Moderne Salzburg / Photo: Rainer Iglar

We also have an ongoing solo exhibition at the Museum de Moderne, Salzburg that opened in November when things were still grand. It’s funny how this show has carried over into this new era of uncertainty and confinement. Though the exhibition is still up through the end of April, it has been closed to the public since mid-March. One of the works in the exhibition, Utopia Workstation, is an interactive piece that invites visitors to compose a utopia of their own design. Installed in one of the Rupertium’s galleries is an immense inflatable bubble in the center of which is a small desk with a manual typewriter, a chair, and, nearby, a waste paper basket. The participant removes his shoes and enters the bubble through an antechamber, then unzips a second portal to access the main chamber where the desk and manual typewriter await. Each participant’s utopia is left in the typewriter carriage for the next participant to read. To write your own utopia though, you must remove the last one. Utopias are after all exclusive. Overflowing the waste paper basket and scattered about the floor of the bubble are all the earlier participants utopias. These are collected and saved by the museum on our behalf for a possible future project.

Utopia Work Station by Walter Martin & Paloma Muñoz / Courtesy Museum der Moderne Salzburg / Photo: Rainer Iglar

Now that many of us are encapsulated in our own private quarantine bubbles we don’t really need to go to the museum to experience the bubble’s rarified space. Even so, the museum has kept the project going online. Visitors are invited to compose and send their utopias to the museum site where they will be added to the many earlier ones done before the pandemic. We are very interested in reading and comparing the earlier ‘good times’ utopias to the ones that may come now in this new age of disenchantment. Imagining a better world even if it is implausible is a positive exercise, especially now.

Blind House. 2014 / © Walter Martin & Paloma Muñoz

Paloma: It has also been a time to reflect upon our previous work. I have been thinking about how it stacks-up against this new reality. How does our Blind House series interface with this new socio-political and economic context? With that series we expressed a sense of dread, a vague suspicion of the risks of globalization and the loss of privacy in the digital age. In this new age of isolation, the internet is the only channel to communicate. It’s the only platform available to find community. The phone, the tablet, the desktop are our exclusive umbilical cords to the world. We are a Spanish-american couple so I also fear that under-the-skin surveillance might become a condition for traveling. The whole traveling paradigm is up in the air. I distrust corporations and government agencies to safeguard all that information. I worry about the loss of freedom that it all entails.

Blind House. 2014 / © Walter Martin & Paloma Muñoz

What is your recipe for survival in a time of almost only bad news?

Walter: I guess to keep grounded in the moment. We find ourselves spending more time writing to friends and communicating with family. It feels retro-futuristic to write long emails instead of just posting as we did when we were so frantically busy. But it feels like we are rediscovering the neglected art of letter writing. It’s a noble form, a kind of diaristic conversation with someone that requires editing and organization. It allows one to articulate and explore the odd daily process of living one’s life and distill it into something evocative, amusing, anecdotal or droll. It’s the perfect place to make conscious note of small things and details that may not be remembered otherwise.

Paloma: Somedays during this quarantine, which seems interminable, I feel really sad or demoralized. I let it happen, the grieving of the world that was, but just for a little while. I try not to let it flow into the next day. The next morning I work towards reconstructing myself, building hope, working a bit, learning. I think curiosity is what keeps me going, a desire to know and to interpret the world.

What is something that we all (each of us, personally) could do to make the world a better place when this disaster comes to an end? It is clear that the world will no longer be the same again, but at the same time...there is a kind of magic in every new beginning.

Walter: There are a lot of people, health care workers in Madrid and Milan and other hot spots who may not have much left to give when this is over. So that’s one thing we should do is make sure they are not forgotten and are never taken for granted or under supplied again. I think our governments have a lot to answer for in that regard and they should be held accountable.

We need to recruit and elect leaders who are competent managers not charismatic snake oil salesmen. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could find qualified leadership with the same sense of selfless professionalism that we have seen exemplified in our health care workers?

Personally I would like to continue this practice of observation and articulation that the quarantine, like some forced monastic retreat, has engendered in us. Quarantine is a sort of state mandated detachment from society. When we were so busy in our former lives, detachment was a quality we tried to cultivate to keep our perspective in the midst of all the collective noise. It’s ironic that we now find ourselves in a world broken, like a continent, into tiny pieces, each of us on our own little island waving, calling out to those closest and wondering about the others.

The art world and the culture sector is one of the most affected. What is the main lesson the art world should learn from all this? How do you imagine the post-apocalyptic art scene?

Paloma: We can´t speak for the art world, but in our experience life teaches lessons to artists everyday – that is practically our job description! We are almost always alone, we are always marginal, we are always struggling. This is not the first time we have gone through a crisis. In the best of times artists have just enough support to continue their practice; sometimes that support disappears completely for long periods of time. It happened after 9/11 in New York: art galleries received some government assistance, but not artists. We had to fend for ourselves. It happened during the Great Recession: we were the first to feel the pain and the last ones to feel the recovery. Every new growth and burst cycle has brought more economic inequality and has concentrated power in fewer hands.

As for the second question: there were never crowds in art galleries and that is why they relied more and more on art fairs packed with people and collectors who attended from all over the world. The art fair model, which was very social, festive even, is what is going to suffer most during this pandemic. Galleries are going to have to go back to the old ways, when they sold in the gallery, at least for a while. That was hard to do! Landlords are going to have to lower rent prices fast, or their spaces will simply go vacant. As for artists, I don´t know, many will have to stop practicing or make less ambitious work.

Walter: There are so many possible future scenarios, it’s hard to jump ahead to a better time post-pandemic that doesn’t take into account the economic/socio-political collapse that comes in its wake. We may see a more decentralized art world that is only held together by the internet. The status quo based on far-flung art fairs, brand-name artists and mega galleries may be an obsolete paradigm, or it may just be temporarily stymied. In an era post globalization, it’s possible a more democratic meritocracy could arise online to supplant the decadent and oppressive art world model where international art gallery consortia – marketing their commodities through art fairs, museums, and art magazines – decide what is art and what is stuff. That would be nice.

El Campello, Alicante. 2020 / © Walter Martin & Paloma Muñoz

FEAR. 2020 / © Walter Martin & Paloma Muñoz (quarantine series)

Wallowing on the Edge, 2020 / © Walter Martin & Paloma Muñoz (quarantine series)

Walter Martin & Paloma Muñoz / Courtesy_Museum der Moderne Salzburg / Photo: Rainer Iglar

***

The artists Walter Martin (1953 Norfolk, VA, US—Milford, PA, US) and Paloma Muñoz (1965 Madrid, ES—Milford, PA, US), who have been partners in life and work since 1993, have risen to renown with photographs and sculptures showing surreal landscape dioramas featuring absurd and bizarre scenes.

Their work is in several museum collections, including Museo Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid and La Caixa in Barcelona, Spain. In 2003, their bronze sculptural work was included in MetroSpective at City Hall Park, sponsored by the Public Art Fund.